Article

in Print Printer-friendly PDF file

Article

in Print Printer-friendly PDF fileWestside Observer

October 2014 at www.WestsideObserver.com

The November 4 Municipal Ballot

Prop “A” and David Chiu: Just Say No

Article

in Print Printer-friendly PDF file

Article

in Print Printer-friendly PDF file

Westside Observer

October 2014 at www.WestsideObserver.com

The November

4 Municipal Ballot

Prop “A”

and David Chiu: Just Say No

by Patrick Monette-Shaw

If the idea of sending Supervisor David Chiu off to represent you in the California Assembly in Sacramento doesn’t scare you enough, get ready for being bilked, San Franciscans.

According to a December 3, 2013 article on StreetBlogSF, you’re being asked to approve half-a-billion dollars for MUNI in 2014 and 10 years from now, the City plans to come back in November 2024 to ask you to approve a second half-a-billion dollars for MUNI, 20 years before the 30-year interest on the first bond will be paid down.

Between the two bonds, taxpayers may have to pay down nearly one billion in interest on the one billion in bonds. Add to that the Mayor’s Task Force recommendation to place a ballot measure before voters in November 2016 to increase San Francisco’s sales tax by a half percent, from 8.75% to 9.25%, designed to help raise another billion dollars for MUNI.

Add onto the mix a ballot measure to raise the vehicle license fee (VLF) from 0.65% to 2% that was planned for the November 2014 election, but which the Mayor pulled off the ballot to make the first $500 million bond for MUNI more palatable to voters hoping for passage of the 2014 bond. Since state law allows San Francisco voters to restore the VLF cut by former Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, do not doubt that the VLF measure recommended by the Mayor’s Transportation Task Force to raise another cool one billion dollars for MUNI will eventually make it onto a future ballot, perhaps in 2016.

Say No to Prop. “A”

If voters approve it, the 2014 Proposition A, the Transportation and Road Improvement Bond, will authorize The City to borrow $500 million by issuing general obligation bonds in order to meet some of the transportation infrastructure needs of the City. The key word is “some,” which is not clearly described.

The Mayor’s Transportation Task Force identified $10 billion in spending on “crucial infrastructure projects” for MUNI earlier in 2014. Proposition “A” funds would be used to address “some” of the needs identified by the task force.

Some observers report

the $500 million in General Obligation Bonds will be accompanied

by $350 million in interest, for a total debt load of $850 million.

Other observers, including transit advocate Howard Wong, assert

that the interest will actually be $500 million.

Some observers report

the $500 million in General Obligation Bonds will be accompanied

by $350 million in interest, for a total debt load of $850 million.

Other observers, including transit advocate Howard Wong, assert

that the interest will actually be $500 million.

The San Francisco Examiner reported on May 14 planned uses of Proposition “A” totaling $472 million, including:

But repeatedly, in both the enabling legislation and the Ballot Simplification Digest in the voter guide, specific projects to be funded are not clearly described. Instead the operative words being put before voters indicate that funds “could be allocated” for transit and roads, or alternatively described as “a portion of the Bond may be allocated to.” Voters beware: The use of the vague words “could be” and “may be” are no substitute for more precise language that uses “shall be.” The choice of words is obviously no mere accident.

There is no mention

in either the Board of Supervisors ordinance or in the Ballot

Simplification Digest itemizing either estimated dollar amounts,

or percentages, of how the funds will actually be allocated across

project categories or to specifically-named projects. The City

is clearly seeking carte blanche authority for unspecified

projects. It wants voters to authorize a half-billion dollar

check having a blank memo line so The City can spend the funds

anyway it pleases.

There is no mention

in either the Board of Supervisors ordinance or in the Ballot

Simplification Digest itemizing either estimated dollar amounts,

or percentages, of how the funds will actually be allocated across

project categories or to specifically-named projects. The City

is clearly seeking carte blanche authority for unspecified

projects. It wants voters to authorize a half-billion dollar

check having a blank memo line so The City can spend the funds

anyway it pleases.

The Ballot Proposal

A list of projects — subject to review and further changes by the Mayor and the Supervisors following the election — for which the bond money “could be” earmarked in the Ballot Simplification Digest includes:

Although the ballot

digest indicates bond funds will be used to improve street conditions,

there is no mention of repaving streets at all in the enabling

Ordinance passed by the Board of Supervisors. The enabling Ordinance

amended by the Board of Supervisors on June 18, 2014 states a

portion of the Bond may be allocated to fund the

City’s share of needed improvements to Caltrain’s infrastructure

to improve reliability, but the ordinance stops short of saying

how much of the bond will be applied to Caltrain’s infrastructure.

Although the ballot

digest indicates bond funds will be used to improve street conditions,

there is no mention of repaving streets at all in the enabling

Ordinance passed by the Board of Supervisors. The enabling Ordinance

amended by the Board of Supervisors on June 18, 2014 states a

portion of the Bond may be allocated to fund the

City’s share of needed improvements to Caltrain’s infrastructure

to improve reliability, but the ordinance stops short of saying

how much of the bond will be applied to Caltrain’s infrastructure.

Wait! What? How did Caltrains get added to this bond measure between the Examiner’s May 14 article itemizing $472 in proposed projects (that made no mention of Caltrains) and June 18, when the Supervisors amended the enabling ordinance?

Oddly, mention of the Caltrains infrastructure is tacked on

to the end of a paragraph in the Ordinance describing potential

improvements to MUNI service reliability designed to reduce travel

time and improve reliability, such as those identified in MUNI’s

Transit Effectiveness Project. What has the Caltrain’s extension

got to do with improving MUNI, or road improvements, the original

intent of Proposition “A”?

Observers are now

wondering whether the Board of Supervisors added the Caltrain’s

improvements to the enabling Ordinance in June knowing that developers

of high-rise buildings around the planned Transbay Transit Center

had hired former Mayor “Slick” Willie Brown to help

them wiggle out of their tax obligations in the Mello-Roos property

tax district surrounding the Transbay Terminal.

Observers are now

wondering whether the Board of Supervisors added the Caltrain’s

improvements to the enabling Ordinance in June knowing that developers

of high-rise buildings around the planned Transbay Transit Center

had hired former Mayor “Slick” Willie Brown to help

them wiggle out of their tax obligations in the Mello-Roos property

tax district surrounding the Transbay Terminal.

As news of the collapse of development deal surfaced and the new “deal” Brown had negotiated surfaced, the San Francisco Chronicle reported on September 25 that the threat of lawsuits by developers threatens not the Transbay Transit Center. Instead, it threatens the Caltrain extension, according to the urban think tank SPUR’s executive director, Gabriel Metcalf. If the development deal collapses and leads to years of litigation, voters may find that the $500 million bond is diverted in large measure to Caltrain’s extension.

Presumably, if the Caltrain’s infrastructure improvements experience cost overruns, the Mayor and Board of Supervisors will have sole discretion to reallocate bond funds among various projects, so other project goals being promised could easily be de-funded to deal with unanticipated increases to Caltrain’s infrastructure. Doesn’t anyone remember the Bay Bridge cost overruns? Or the Central Subway boondoggle?

According the Board of Supervisors ordinance dated June 18, 2014 placing the bond measure on the November ballot, broad brush-stroke goals of potential bond projects may include:

While these are laudable goals after decades of underfunding street maintenance, the broad brushstroke of categories do not provide any description of specific projects whatsoever. And despite being laudable goals, since the ballot measure provides that use of the bond funds will be subject to “review and further changes” by the Mayor and Supervisors, there’s no guarantee that once given a $500 million blank check, that any of the goals will actually be addressed. There’s nothing preventing the Mayor from diverting the full check to Caltrains.

Lack of Oversight

Remember the Emperor’s

new clothes? Or remember the wizard behind the curtain in the

Wizard of Oz?

Remember the Emperor’s

new clothes? Or remember the wizard behind the curtain in the

Wizard of Oz?

Such will be oversight regarding the Prop. “A” bond program. Although both the enabling legislation and the ballot digest promise earnestly that the bonds will face oversight by San Francisco’s Citizen’s General Obligation Bond Oversight Committee (CGOBOC), effective oversight will be meaningless given that the enabling Ordinance provides no specifics on which transportation-related projects will ultimately receive bond financing and at what dollar amounts, despite the San Francisco Examiner’s reporting of specific dollar amounts per project category.

Absent being provided a clearly enumerated yardstick of budgeted dollars-per-category, CGOBOC will have no way of evaluating whether bond funds are being spent as intended. Instead, CGOBOC will only serve as a rubber-stamp agency, evaluating quarterly whether bond projects are being expended and obligated. As the Mayor and Board of Supervisors tinker with allocation of the bond following voter passage of the measure, CGOBOC will only be able to rule that the goal posts have been moved around as it reviews bond spending.

If the goal posts can be picked up and moved around by the Mayor and Board of Supervisors at will post-election, how will CGOBOC be able to provide any sort of meaningful citizen oversight? By following a bouncing ball?

Residential Parking Permits May Be Tapped, Next

Back on July 29, 2011, the StreetBlogSF carried an article regarding the November 8, 2011 ballot measure titled “Road Repaving and Street Safety Bonds.” StreetBlogSF reported that Tom Radulovich — the then executive director of Livable City who has been an elected member to BART’s Board of Directors since November 1996 — said back in 2011 that the City should consider user fees such as congestion pricing, a gas tax, or adjusting the price of residential parking to help fund street repaving and parking maintenance.

Reportedly, during

the recent past Radulovich has again pressed the SF Municipal

Transportation Agency to conduct a more in-depth study to include

in Residential Parking Permit fees an increase to fund some proportional

share of roadway wear-and-tear maintenance and repair, in addition

to purely administrative costs.

Reportedly, during

the recent past Radulovich has again pressed the SF Municipal

Transportation Agency to conduct a more in-depth study to include

in Residential Parking Permit fees an increase to fund some proportional

share of roadway wear-and-tear maintenance and repair, in addition

to purely administrative costs.

Such a study to determine costs related to damage to streets is exactly the same issue that the City passed on (avoided) when it recently calculated permit costs for corporate shuttle buses, such as the Google buses, that weigh 10 times what a passenger car weighs. And the cars in question are parked, not buses driving on the roadways.

Apparently, Radulovich’s philosophy is that individual car owners (persons) can be taxed (via “fees”) using residential parking permits for street repairs, but corporations (who are not persons, albeit Citizens United) cannot be taxed for the same purpose.

Put aside for a moment that San Francisco residential parking permit holders may face an increase to their parking permit fees, while out-of-town commuters and commercial business vehicles may not face the same assessment to repair our roads.

Then ask yourself why Radulovich would back creating a potentially illegal tax restricted to parking permit holders, ignoring that regulatory charges must be assessed to all users, apportioned to use.

MUNI’s Five-Year Budget

Given the five-year

history of MUNI’s budgets, voters should be skeptical of

handing MUNI any more money using vaguely-worded ballot measures.

Given the five-year

history of MUNI’s budgets, voters should be skeptical of

handing MUNI any more money using vaguely-worded ballot measures.

Data available on The City’s SFOpenBook web site shows that across the past five years, MUNI’s budget has soared by $172.9 million, up from $775 million in FY 10–11 to $947.9 million for the current FY 14–15 — a whopping 22.2% increase. Of the $172.9 million increase, $93.9 million occurred between FY 13–14 and FY 14–15.

Across the four-year period from calendar year 2010 to calendar year 2013, MUNI added 221 employees pushing its total payroll (excluding fringe benefits) up just $30.1 million, from $375.4 million in CY 2010 to $405.5 million in CY 2013, leading observers to wonder why MUNI’s budget increased $172.9 million between FY 10–11 and FY 14–15 and what the $173 million was spent on, if not on salaries.

There are few signs that increasing MUNI’s budget has improved the system overall, or improved on-time performance.

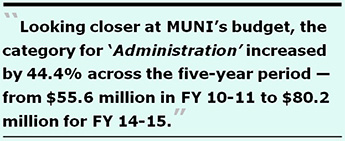

Looking closer at MUNI’s budget, the category for “Administration” increased by 44.4% across the five-year period — from $55.6 million in FY 10–11 to $80.2 million for FY 14–15. Why did Administration need a $24.6 million increase?

Another category in MUNI’s budget, “Parking Garages and Lots,” saw a 120.2% increase across the five-year period, from $21.9 million in FY 10–11 to $48.1 million for FY 14–15.

By way of contrast,

the category “Parking and Traffic” saw a modest

21.6% increase from $72.6 million in FY 10–11 to $88.3 million

for FY 14–15. MUNI is now budgeting almost as much for “Administration”

as it does for “Parking and Traffic” operations. Similarly,

the category “Rail and Bus Services” increased

only 25.1%, from $422.2 million in FY 10–11 to $528.1 million

for FY 14–15.

By way of contrast,

the category “Parking and Traffic” saw a modest

21.6% increase from $72.6 million in FY 10–11 to $88.3 million

for FY 14–15. MUNI is now budgeting almost as much for “Administration”

as it does for “Parking and Traffic” operations. Similarly,

the category “Rail and Bus Services” increased

only 25.1%, from $422.2 million in FY 10–11 to $528.1 million

for FY 14–15.

Before voters hand MUNI $500 million in new bond funding via Prop “A,” reasonable questions include whether the agency has too much bloat in its budget; whether it needs a department-wide comprehensive, and independent, audit; and whether the agency has been a good steward of public funds.

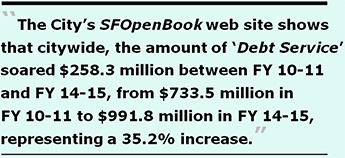

The City¹s Overall Debt Service

Similarly, data available on The City’s SFOpenBook web site shows that citywide, the amount of “Debt Service” soared $258.3 million between FY 10–11 and FY 14–15, from $733.5 million in FY 10–11 to $991.8 million in FY 14–15, representing a 35.2% increase. The City’s current billion-dollar debt service represents fully 11% of San Francisco’s $8.6 billion budget for FY 14–15.

Do the Mayor and Board of Supervisors really expect that two-thirds of San Francisco voters will be in favor of tacking on another $350 million to $500 million in interest on the Prop. “A” bond, adding another half-billion in debt service to the current billion already budgeted for debt service?

Say “No” to David Chiu

Leading up to the

June 2014 primary election, readers may recall in-depth reporting

about the race between Supervisors David Campos and David Chiu

to replace termed-out Assemblyman Tom Ammiano in this reporter’s

article “The Three-David Race for Assemblyperson”

on the Fog City Journal web site last May. Since then,

the race between the two David’s has become neck-and-neck,

and additional information has surfaced about why you won’t

want to send Mr. Chiu to Sacramento.

Leading up to the

June 2014 primary election, readers may recall in-depth reporting

about the race between Supervisors David Campos and David Chiu

to replace termed-out Assemblyman Tom Ammiano in this reporter’s

article “The Three-David Race for Assemblyperson”

on the Fog City Journal web site last May. Since then,

the race between the two David’s has become neck-and-neck,

and additional information has surfaced about why you won’t

want to send Mr. Chiu to Sacramento.

Chiu and Residential Parking Permits

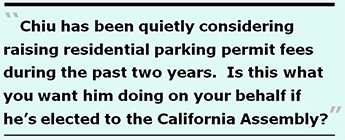

Not only has BART board member Radulovich been interested for several years in exploring increasing Residential Parking Permit (RPP) fees to include an assessment for street wear-and-tear resurfacing programs, apparently so too has been Supervisor David Chiu.

In 2009, Chiu was quoted in the SFStreestblog on July 21, 2009 as being concerned about a San Francisco County Transportation Authority parking study. In particular, Chiu was concerned about the impact of increased on-street parking fees on low-income residents who don’t have access to garages.

Two years later in 2011, Chiu displayed a diminishing concern for low-income residents, when he responded to a South Beach–Rincon–Mission Bay Neighborhood Association candidate questionnaire saying that the City “should explore whether our residential parking program adequately captures the real cost of street parking.”

By 2013, Chiu appears to have forgotten his concerns for low-income residents. Chiu apparently requested that SF MTA’s General Manager, Ed Reiskin, perform a study of the RPP program, with a goal to associate additional costs and allow an increase to parking permit fees.

In a March 26, 2013 e-mail from Reiskin (who earned $305K as MTA’s General Manager in 2013) to two of his Deputy Directors (Bond Yee, who earned $215K and Sonali Bose, who earned $226K), Reiskin wrote:

Reiskin’s e-mail

subject line read “RPP fee nexus study.”

Reiskin, like Radulovich and Supervisor David Chiu, has to know

that the City eliminated apportioning a share of roadway damage,

wear-and-tear maintenance, and street repair when the corporate

shuttle bus fees were calculated.

Reiskin’s e-mail

subject line read “RPP fee nexus study.”

Reiskin, like Radulovich and Supervisor David Chiu, has to know

that the City eliminated apportioning a share of roadway damage,

wear-and-tear maintenance, and street repair when the corporate

shuttle bus fees were calculated.

It appears Chiu has been quietly considering raising residential parking permit fees during the past two years. Is this what you want him doing on your behalf if he’s elected to the California Assembly? If not, vote for David Campos, not David Chiu, for Assembly District 17.

Airbnb and the “Sharing Economy”

Although New York City; Berlin, Germany; and other cities are taking steps to ban short-term rentals altogether, Supervisor Chiu continues his attempts to write legislation to “regulate” — rather than ban — short-term rentals in San Francisco.

Problems with Airbnb have surfaced in many neighborhoods throughout San Francisco, from West Portal to single-room-occupancy (SRO) hotels in the Tenderloin. The San Francisco Weekly reported on September 17 that in September, Airbnb was hit with a class action lawsuit filed in San Francisco Superior Court by tenants of the Sheldon Hotel in the Tenderloin accusing Airbnb of illegally converting SRO rooms into transient hotel rooms. On August 6, the San Francisco Examiner reported problems of SRO rooms in Chinatown also being listed on Airbnb.

According to amendments made to Chiu’s short-term rental legislation on September 29, it doesn’t appear that Chiu added any provisions to his legislation to protect SRO rooms from conversion to short-term rental rooms.

As I reported last

May on FogCityJournal.com, Supervisor

David Chiu has taken over two years to develop legislation regulating

“sharing economy” short-term rentals in San Francisco.

Chiu’s two-year delay may have benefited Airbnb and its

prime investor, billionaire Ron Conway, who holds considerable

sway over Mayor Ed Lee after Conway formed an independent expenditure

committee that spent $600,000 towards electing Lee as Mayor in

2011.

As I reported last

May on FogCityJournal.com, Supervisor

David Chiu has taken over two years to develop legislation regulating

“sharing economy” short-term rentals in San Francisco.

Chiu’s two-year delay may have benefited Airbnb and its

prime investor, billionaire Ron Conway, who holds considerable

sway over Mayor Ed Lee after Conway formed an independent expenditure

committee that spent $600,000 towards electing Lee as Mayor in

2011.

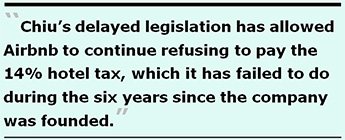

Chiu’s delayed legislation has allowed Airbnb to continue refusing to pay the 14% hotel tax, which it has failed to do during the six years since the company was founded. Current estimates project that the City would receive $11 million annually if Airbnb would begin paying the hotel tax; over the six-year period it has refused to pay the tax, San Francisco has lost somewhere between $66 million and $100 million in revenue, a fact that cannot have escaped investor Conway’s notice.

On April 3, 2012, San Francisco Treasurer and Tax Collector Jose Cisneros published an opinion that short-term rental companies and their hosts are required to collect and pay the city’s Transient Occupancy Tax (the hotel tax). On the day Cisneros published his opinion, the SF Bay Citizen reported that Mayor Lee’s office “had urged Cisneros … to postpone applying the rule to give a ’collaborative consumption task force’ time to consider possible legislation that would apply a lower tax rate” on brokers of short-term rentals. The term “collaborative consumption” is used to describe the so-called “sharing economy” … although “sharing economy” companies such as Airbnb don’t actually pay their fare share of taxes.

For his part, Mayor

Lee has offered no explanation as to why a lower tax rate should

be granted to Airbnb and its prime investor, Ron Conway. Perhaps

Lee is counting on Conway spending more independent expenditure

committee funds to re-elect him to a second term as mayor and

doesn’t want to annoy his “angel” investor.

For his part, Mayor

Lee has offered no explanation as to why a lower tax rate should

be granted to Airbnb and its prime investor, Ron Conway. Perhaps

Lee is counting on Conway spending more independent expenditure

committee funds to re-elect him to a second term as mayor and

doesn’t want to annoy his “angel” investor.

The Mayor sought to delay Cisneros’ ruling in order to have “a policy discussion first, so we can see how to support companies built around the model of collaborative consumption.” In other words, Chiu’s two-year delay on his Airbnb legislation has involved a two-year policy discussion directed by the Mayor to help support investor Conway and to help Airbnb avoid being required to start paying the hotel tax, or to pay substantial back-taxes it already owes.

On August 14, 2014, the San Francisco Examiner reported that the Department of Building Inspection’s (DBI) Code Advisory Committee believes that Chiu’s legislation to regulate short-term rentals “still fails to address fire-safety, life-safety, accessibility and occupancy issues,” and argued that DBI should not be an administrative record-keeping agency monitoring short-term rentals by being required to operate a registry of hosts using short-term rental platforms like Airbnb.

The Code Advisory Committee noted Chiu’s legislation didn’t initially add safety codes to the short-term rentals beyond what currently exist for residential units, and didn’t provide for code-compliance checks for issues such as smoke detectors.

Between August 14

when the Code Advisory Committee expressed its concerns and September

15 when the legislation was heard by the Board of Supervisors

Land Use Committee, Chiu had taken no action to include the Code

Advisory Committee’s concerns.

Between August 14

when the Code Advisory Committee expressed its concerns and September

15 when the legislation was heard by the Board of Supervisors

Land Use Committee, Chiu had taken no action to include the Code

Advisory Committee’s concerns.

The San Francisco Chronicle reported on September 17 that Chiu had belatedly agreed to add a provision to suspend rentals in units found to violate city codes for electrical, plumbing, and other systems, but many observers remain concerned that Chiu’s legislation doesn’t go far enough to require compliance with The City’s safety codes.

Following the Land Use Committee hearing on September 15, Chiu amended his legislation on September 29 placing the burden of making sure there are no code violations on the resident who is seeking to rent out her or his unit as a short-term rental, and added that if code violations occur after a residential unit has been added to the short-term renal registry, the Planning Department will suspend the registration until the code violation has been cured, essentially making it the tenant’s responsibility to get their landlord to fix code violations.

It’s unclear whether members of the Land Use Committee addressed all of the Code Advisory Committee’s concerns about Chiu’s short-term rental legislation.

During the September

15 Land Use Committee hearing, Supervisors pushed David Owen,

Airbnb’s director of public policy, for information on liability

insurance and the number of nights hosts can rent out their units.

Owen — who served as a legislative assistant to former Supervisor

Aaron Peskin between July 2003 and July 2006, and again between

September 4, 2008 through January 13, 2009 — creatively claimed

that reporting to The City the number of nights each unit is used

would violate Airbnb’s “innovations,” and violate

the privacy of hosts renting out their units. Owen has refused

to comment on whether Airbnb will pay its back taxes, despite

Cisneros’ 2012 ruling and Peskin’s belief the back taxes

should be paid.

During the September

15 Land Use Committee hearing, Supervisors pushed David Owen,

Airbnb’s director of public policy, for information on liability

insurance and the number of nights hosts can rent out their units.

Owen — who served as a legislative assistant to former Supervisor

Aaron Peskin between July 2003 and July 2006, and again between

September 4, 2008 through January 13, 2009 — creatively claimed

that reporting to The City the number of nights each unit is used

would violate Airbnb’s “innovations,” and violate

the privacy of hosts renting out their units. Owen has refused

to comment on whether Airbnb will pay its back taxes, despite

Cisneros’ 2012 ruling and Peskin’s belief the back taxes

should be paid.

The final, September 29 draft of Chiu’s legislation that the full Board of Supervisors is scheduled to vote on whether to adopt on October 7 contains no requirement for Airbnb to pay its back taxes. Reasonable observers note that it is simply bad policy to create legislation approving short-term rentals without requiring a hosting platform like Airbnb to pay in full its illegal and overdue back taxes (plus interest and late-fee penalties) before rewarding them with legislation legitimizing hotelization of The City’s limited housing stock. It’s akin to sanctioning illegal corporate behavior and then rewarding them for not paying back taxes, particularly since there is no guarantee from David Owen that Airbnb will actually begin paying taxes going forward.

Chiu’s legislation appears to be restricted to a 90-day limit when a host is not present, but the Land Use Committee debated, but has not yet required, that a similar limit should be applied when hosts are present, since without an explicit restriction there’s a clear loophole allowing hosts to be able to rent out portions of their units all year long provided they are present. As of September 18 a cap limiting how often hosts can rent out rooms while present remains undetermined, and is not included in Chiu’s final legislation.

Supervisor Jane Kim is concerned that if Chiu’s legislation does not include regulating co-hosted days, and if Airbnb continues to refuse disclosing room rental data, the City will have no way to enforce Chiu’s legislation as written. Chiu’s amendments added on September 29 do not appear to address Kim’s concern regarding co-hosted days.

The Land Use Committee

reportedly requested an amendment to Chiu’s legislation that

tenants must notify their landlord if they register as a “host”

on a hosting platform such as Airbnb, a key provision that Chiu

failed to include all along, as if landlords have no say in whatever

happens in their rental units. Chiu’s September 29 amendments

added a provision that when a short-term rental application has

been submitted, the Planning Department will then send a notice

to the landlord, after the fact. Imagine a landlord’s shock

learning of their tenant’s short-term rental plans only after-the-fact,

via a notice received from the Planning Department.

The Land Use Committee

reportedly requested an amendment to Chiu’s legislation that

tenants must notify their landlord if they register as a “host”

on a hosting platform such as Airbnb, a key provision that Chiu

failed to include all along, as if landlords have no say in whatever

happens in their rental units. Chiu’s September 29 amendments

added a provision that when a short-term rental application has

been submitted, the Planning Department will then send a notice

to the landlord, after the fact. Imagine a landlord’s shock

learning of their tenant’s short-term rental plans only after-the-fact,

via a notice received from the Planning Department.

Common sense suggests that a written notice from a landlord approving a tenant’s plan to sublet their unit for short-term rentals should have been a required document as part of a tenant’s application packet to the Planning Department, prior to issuing a short-term rental registration number and adding the unit to the registry.

The Land Use Committee should insist that Chiu’s legislation add a provision that unless Airbnb pays the back taxes the City is owed, that the legislation is dead on arrival and will not to be approved by the full Board of Supervisors until the past-due tax bill is paid.

Indeed, Airbnb’s “sharing economy” business model appears to be based on flouting laws on the books regulating various public accommodations. Take for instance an August 20 article in San Francisco Weekly reporting that Airbnb had launched a pilot program to allow city residents to register for its “dinner party program.” Last June, Airbnb began piloting a new twist to its home-sharing platform in which “hosts” will be able to throw paid dinner parties for total strangers while violating all sorts of regulations that apply to brick-and-mortar restaurants.

SF Weekly reported

that Richard Lee, head of San Francisco Department of Public Health’s

food safety program, noted that for-profit hosts running what

amounts to a restaurant out of their homes is completely illegal.

That hasn’t stopped Airbnb. It’s another illegal ancillary

venture following Airbnb’s illegal venture in short-term

rentals.

SF Weekly reported

that Richard Lee, head of San Francisco Department of Public Health’s

food safety program, noted that for-profit hosts running what

amounts to a restaurant out of their homes is completely illegal.

That hasn’t stopped Airbnb. It’s another illegal ancillary

venture following Airbnb’s illegal venture in short-term

rentals.

Chiu’s legislation does nothing to stop Airbnb from encouraging its “hosts” to sell home-cooked meals as an ancillary service, sales from which Airbnb will pocket a cut. Chiu will likely not develop additional regulations governing “sharing economy dinner parties,” perhaps out of deference to his benefactor, Ron Conway.

Forewarned is Forearmed

Voters rejected and defeated a similar street repaving and construction bond measure in 2005 when it failed to obtain a two-thirds majority at the ballot box. Voters should do so again, by rejecting Prop. “A” this November.

After all, Airbnb and the Transbay developer’s refusal to pay their fair share of taxes opens the door to having Prop. “A’s” $500 million bond diverted to completing the Caltrain extension, post-election.

Developers, high-tech companies, and “sharing economy” companies don’t want to pay their fare share of taxes — and have successfully avoided paying taxes in San Francisco for years — and want voters to bear the tax burden, instead.

To avoid David Chiu pulling his same stunts in Sacramento affecting

the rest of the State, vote for David Campos, and urge your friends

and relatives living in Assembly District 17 to do the same.

Say “No” to both Prop. “A” and to David Chiu.

Monette-Shaw is an open-government accountability advocate, a patient advocate, and a member of California's First Amendment Coalition. He received the Society of Professional Journalists-Northern California Chapter’s James Madison Freedom of Information Award in the Advocacy category in March 2012. Feedback: mailto:monette-shaw@westsideobserver.