Article

in Print Printer-friendly PDF file

Article

in Print Printer-friendly PDF fileWestside Observer

April 2014 at www.WestsideObserver.com

On the Mayor’s Seven-Point Housing Plan

Affordability Mayor: A Housing Bait-and-Switch?

Article

in Print Printer-friendly PDF file

Article

in Print Printer-friendly PDF file

Westside Observer

April 2014 at www.WestsideObserver.com

On the

Mayor’s Seven-Point Housing Plan

Affordability

Mayor: A Housing Bait-and-Switch?

by Patrick Monette-Shaw

To believe Mayor Ed Lee’s pledge to build 30,000 housing units in San Francisco over the next six short years, you’d also have to believe P.T. Barnum said “There’s a sucker born every minute.” [It wasn’t Barnum who said it; Wikipedia indicates several sources attribute the aphorism to various con men.]

For openers, although the mainstream media reported January 17 details of Mr. Mayor’s seven-point plan to solve the City’s number one crisis (affordable housing), the media failed to note the Mayor’s bloviated claim to issue 2,500 down-payment-assistance loans during the next six years — and increase each loan to up to $200,000 — may end up costing a half-billion dollars. The media didn’t report, and apparently didn’t bother asking, where the Mayor plans to come up with a cool $500 million in order to hand out 2,500 interest-free loans within six years.

Will

Google, or Twitter — or Ron Conway, and Danielle Steele’s

ex-hubby, Tom “Don’t Persecute Billionaires” Perkins

— donate upwards of $450 million out of their collective

“tech” deep pockets to make these interest-free loans

happen?

After all, the enabling legislation passed by voters in November 2012 authorized the Mayor’s new Housing Trust Fund to receive just $36.8 million in diverted-from-the-General-Fund appropriations during the same six-year period. How do you divide $36.8 million in fish and loaves, and come up with $500 million? Using bloviated fish? By cracking open a magnum of a City Hall mixologist’s “infused” wine?

Unfortunately, public safety employees in San Francisco — and particularly, citizens who vote — appear to have been played for a sucker over the Housing Trust Fund approved by voters in November 2012, a fund administered by the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development.

The Housing Trust Fund appears to potentially be a bait-and-switch all of its own.

Proposition “C” approved by voters on the November 2012 ballot permitted the City to divert $20 million annually from the City’s General Fund towards constructing housing (without explaining what General Fund programs would face the chopping block to free up $20 million annually). The City will add an additional $2.8 million annually to the Housing Trust Fund on a compounded basis for the next 11 years, until 2024–2025.

By

the time 2025 rolls around — just 12 years into this program

— the General Fund will be tapped for $50.8 million annually

for this Housing Trust Fund (again with no mention of what else

will be cut from the General Fund). By 2025, a combined $424 million

will have been diverted from the General Fund to the Housing Trust

Fund.

Between 2025 and 2043 (since it’s a 30-year program), the annual allocation to the Trust Fund will be based on the prior year’s appropriation that will ostensibly start at $50.8 million, adjusted plus or minus an unspecified percentage of change to the City’s General Fund Discretionary Revenues. By 2043 — assuming a flat contribution of $50.8 million annually in each of the next 18 years — an additional $914.4 million will be generated, bringing the total 30-year contributions to the Housing Trust Fund to a staggering $1.34 billion promised for a wide variety of housing, not just down-payment assistance loans.

Raising $500 million for down-payment assistance loans is scheduled to take at least 14 years, not the six years reported in the media. And that would assume that the first $500 million in General Fund contributions to the Housing Trust Fund would be used solely for down-payment assistance loans, and all other housing programs would receive nothing during those 14 years.

Nobody — certainly not the Mayor or the major media — is talking about the $1.34 billion in General Fund cuts that will be required in order to fatten up the Mayor’s Housing Trust Fund using diverted money, with no information on what will be cut and who will be affected. General Fund cuts will certainly happen, given the Mayor’s claim of looming City budget deficits projected for at least the next three years.

In

the next six years, will we be any closer to having any of the

housing built promised by the Mayor and his Housing Trust Fund?

Probably not. Just take a look at the dismal performance of the

Housing Trust Fund so far. But first, take a look at the Mayor’s

recent past for some context.

Mayor Lee Whipped at the Ballot Box

You wouldn’t know it from the dearth of post-election news analysis by our major media, but there were a number of significant losers in San Francisco’s municipal election last November.

When voters rejected Proposition “B” on the November 2013 ballot by a whopping 63 percent, they rebuffed the developers of luxury condos who had asked voters whether the City should allow development at 8 Washington Street. Mayor Lee was among the official proponents of the ballot measure. The same voters also rejected Proposition “C” at the same time, which was a referendum on whether the Board of Supervisors spot-zoning height increase for 8 Washington should take effect. More emphatically, over two thirds of voters — 67 percent — cast “No” votes.

The

biggest loser over Propositions “B” and “C”

was Mayor Lee — who lost any hope that his “legacy”

project of the Warrior’s stadium planned to be built on the

Bay exceeding height zoning would survive voter scrutiny, forcing

Lee to go in search of his next “legacy.”

Other losers included the Board of Supervisors, trounced by referendum of the people against the Board’s flagrant use of spot-zoning height increases along the waterfront. The twin losses for Lee and the Supervisors so rattled them, that none of them dared to become the official opponent of the upcoming Proposition “B” on the June 2014 ballot that would require each project proposed for development on the waterfront that would exceed current height restrictions to obtain project approval by voters at the ballot box, beforehand.

A poll conducted for the Harvey Milk Club last December shows 75 percent of likely San Francisco voters favor this June 2014 ballot measure, which will probably pass handily. Also listed in the 2012 voter guide as proponents of the 8 Washington ballot measure, Supervisors Mark Farrell and Scott Wiener suffered an embarrassing loss at the ballot box. Wiener and Farrell hate losing. No wonder there were no takers to be the voter guide opponent on June’s Prop “B.”

And

finally, the losers include the California State Teachers Retirement

Fund (CalSTRS). As the Westside Observer reported in September 2013, an October 30,

2008 letter to the San Francisco Port Authority pledged that CalSTRS

would make an equity contribution in the range of $100 million

for project rights to 8 Washington. A February 19, 2009 Port Authority

memo stated CalSTRS would have a 99 percent ownership interest

in 8 Washington. As of September 2013, CalSTRS had invested $42

million in the 8 Washington project.

It isn’t clear how much the teacher’s pension fund lost when 8 Washington went down to double defeat, but it is known that CalSTRS lost over $100 million in a failed attempt to convert Stuyvesant Town — 11,250 middle class rent-controlled apartments in New York City’s Peter Cooper Village — into high-end luxury housing. Not to be outdone, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System lost $970 million it had paid to Lennar Housing in 2007 for part of a stake in Newhall Land Development Company’s “Newhall Ranch” deal north of Los Angeles that went bankrupt when the housing market crashed in 2008.

You have to wonder why Major Lee is cavorting with Lennar Urban’s massive housing development project in the Bayview Hunter’s Point and Lennar’s development on Treasure Island, given that Lennar’s Mare Island project was reported in July 2013 to also be in bankruptcy. Hopefully, Lee’s legacy will not be “the bankruptcy mayor.”

Housing Trust Fund Components

The

November 2012 voter guide stratified how the $20 million Housing

Trust Fund would be put to use, terms of which were to be determined

by the sole discretion of the Mayor’s Office of Housing.

First, the voter guide indicated an unspecified amount would be

used to create, acquire, or rehabilitate rental and home ownership

for households earning up to 120 percent of Area Median Income

(AMI), including acquisition of land. The AMI amount as of January

2014 is $67,950 for a one-person household, and $104,850 for a

five-person household; 120 percent translates to $81,550 and $125,800,

respectively.

Second, the 2012 voter guide indicated that no later than July 2018, the City would appropriate $15 million from the Trust Fund for down-payment loan assistance programs of up to 120 percent of AMI — ostensibly for non-first responders — and an unspecified percent of AMI for public safety first responders. The percentage of AMI for first responders was to be set at the sole discretion of the Mayor’s Office of Housing, but Supervisor Mark Farrell infused himself into the “sole discretion” discussions. Farrell is just one of City Hall’s creative mixologists infusing the wine.

Third, the voter guide reported that also by July 2018, the City will appropriate another $15 million from the Trust Fund for use as “assistance to reduce the risk to current occupants of a loss of housing,” and for use in making their homes safer, more accessible, energy efficient or “more sustainable” under a “Housing Stabilization Program” component of the Trust Fund for residents earning up to 120 percent of AMI.

Fourth, the Trust Fund would be permitted to use funds to operate and administer a “Complete Neighborhoods Infrastructure Grant Program” to accelerate the build-out of public realm infrastructure needed to support increased residential density. The Infrastructure Grants would be used only for public facilities identified by California’s Community Facilities District laws, and would give priority to residential development “project sponsors, community-based organizations, and City departments” for public realm improvements associated with proposed residential development projects. Funding would be restricted to no more than $2 million annually, or 10 percent of appropriations in any given year. [By 2025, 10 percent of the $50.8 million annual contribution to the Housing Trust Fund translates to $5.8 million for infrastructure grants.]

Fifth,

the voter guide indicated the City could allocate an unspecified,

but “sufficient amount” to cover legally permissible

administrative costs of the Fund, including legal expenses and,

ostensibly, personnel costs.

But the voter guide never told voters that up $1.34 billion would be provided to the Housing Trust Fund over the 30-year legislation. Still, lured by the smell of money, voters passed Proposition “C” all but ignoring that it contained a poisoned pill buried in the legal text of the initiative: For certain residential projects beginning after January 2013, the City would be required to reduce — by a staggering 20 percent — the current on-site inclusionary housing obligations of developers to develop “affordable” inclusionary housing.

The voter guide also stipulated that as of January 2013 the City would not be allowed to adopt any new land use legislation or administrative regulations that would require project sponsor’s to increase their inclusionary housing cost obligations beyond those required on January 1, 2013, including the 20 percent reduction.

You’d need to be a land-use attorney to understand which sections of the Planning Code would be subject to the 20 percent reduction to inclusionary housing requirements, which appears to be a reward to developers for not opposing Proposition “C” at the ballot box. After all, the developers are anxious to milk the $1.34 billion Housing Trust Fund.

To the extent Prop. “C” was backed by the Mayor, you have to wonder about his claims concerning “affordability,” given the poison pill in the November 2012 Proposition “C” that reduced affordable inclusionary housing by 20 percent in order to placate developers and investors.

The Eligibility Feeding Freenzy

Within two months of his stinging defeat over 8 Washington last November, the Mayor’s social media spin doctors had created a new persona for him: That as the “affordability mayor” pushing an “affordability agenda.”

The ensuing food fight that broke out over use of the Housing Trust Fund was nasty. Back in July 2013, just after the City adopted its fiscal year 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 budget, a coalition of advocates tried to broker an agreement that not only would teachers and nurses be eligible for the down-payment loan assistance programs (DLAP) along with police, firefighters, and sheriff employees, but all City workers would be eligible, too.

In

particular, public safety dispatchers who dispatch 9–1–1

calls to police officers and firefighters had sought to be included

in the first round of loan funding, but were rebuffed, as were

the teachers and nurses. Supervisor Farrell fought bitterly with

the Mayor’s Office of Housing (MOH) during negotiations regarding

eligibility for the so-called “first responders” carve

out from the DLAP funds. Farrell had initially wanted firefighters

and police officers to be allowed to earn up to 250 percent of

AMI, which would have equaled $169,875 for a one-person household,

and up to $262,125 for a five-person household.

Supervisor Farrell’s meddling prevented the 9–1–1 dispatchers from eligibility, and dispatchers may not have been informed they could apply under a separate non-first responder’s down-payment assistance loan program, instead.

On July 30, 2013 Farrell spoke at a City Hall news conference flanked by Fire Chief Joanne Hayes-White, Police Chief Greg Shur, and Mayor Lee. Farrell announced that the DLAP loans would be restricted to public safety first responders, with a maximum down-payment loan assistance amount of $100,000. Farrell — like others — hope to entice public safety officers to move back into San Francisco from other jurisdictions. Fat chance.

According to an article in the San Francisco Chronicle the next day, reportedly “more than 45” police, fire, and sheriff personnel had expressed interest in applying for the first responder DLAP loans. The Chronicle didn’t report on whether Farrell mentioned during his news conference that a second DLAP program for non-first responders was also under development.

Farrell doesn’t seem to get it — as most politicians don’t — that without 9–1–1 dispatchers residing in the City and County, police, fire, and other first responders will have insufficient dispatchers directing them to 9–1–1 emergencies following earthquakes or other disasters. After all, 9–1–1 dispatchers are the City’s first, first responders.

Eligibility Conundrum: 9–1–1 Dispatchers vs. Public Safety vs. Others

The first-responders DLAP program was created in November 2012 to help entice public safety personnel to move back to San Francisco from outlying jurisdictions. Presumably, after the next big earthquake or other disaster, there are too many public safety officers residing out of county, and recovery efforts will be stymied by the inability of staff to get back into the City to provide public safety.

Data from the City’s Department of Human Resources obtained in January 2014 shows that:

The

number of police, fire, sheriff, and dispatchers who live out

of county is a combined 73 percent, a figure that probably has

disaster recovery planners and resiliency planners very worried.

Why isn’t Supervisor Farrell worried about reducing the number

of dispatchers residing out-of-county? Does Farrell think the

police and firefighters can dispatch themselves, given an insufficient

number of 9–1–1 dispatchers who currently reside in-county?

The

number of police, fire, sheriff, and dispatchers who live out

of county is a combined 73 percent, a figure that probably has

disaster recovery planners and resiliency planners very worried.

Why isn’t Supervisor Farrell worried about reducing the number

of dispatchers residing out-of-county? Does Farrell think the

police and firefighters can dispatch themselves, given an insufficient

number of 9–1–1 dispatchers who currently reside in-county?

And as far as the maximum income levels issue goes, if eligibility for one-person households earning up to 200 percent of AMI is currently set at $135,900, fully 94.4 percent of line-staff dispatchers would qualify and 96.9 percent of dispatch supervisors would qualify, as would 78 percent of Sheriff’s safety personnel. This contrasts starkly to just 46.6 percent of police officers who would qualify, and just 22.4 percent of firefighters and paramedics who would, according to payroll data provided by the City Controller.

When it comes to maximum income eligibility levels for four-person households earning up to 200 percent of AMI currently set at $194,200, fully 100 percent of both dispatch line staff and their supervisors would qualify, as would 98 percent of police officers and Sheriff’s staff, compared to only 75.9 percent of firefighters and paramedics who would.

But with all that said, there is no data available that could be requested from the City to analyze either: 1) How many potentially-eligible police, firefighters, Sheriff’s deputies — or even 9–1–1 dispatchers — may have double- or total-household income levels (including spouses and any other income-earning members residing in their households) that would disqualify them from either the 120 percent or 200 percent of AMI restriction?; and 2) How many of the police, firefighters, and Sheriff’s deputies versus the dispatchers already own homes, and, therefore, may be ineligible under first-time buyer restrictions?

That may explain why Flannery reported that there were just 12 first responders who were drawn in the first-year lottery for the DLAP loans: Their total household income may be far higher than the maximum percentage of AMI permitted, or they may already own homes, making them ineligible under either criteria.

Had dispatchers been eligible for the first-year lottery, perhaps more than four loans may have already been awarded. Or, had Farrell not infused himself as a mixologist during the eligibility food fight, perhaps by having opened up eligibility to nurses or teachers — or to all City employees — it may have yielded a better first-year use of the DLAP funds that remain unspent nine months into the current fiscal year.

Lack of Documentation

On

December 29, this author placed a records request to Mayor Lee

asking for a list of the first and last names, job classification

codes, and City Department of each applicant who had applied

for assistance under the Prop. “C” down-payment loan

assistance program once the program began accepting applications

in August 2013. Also requested was a second list of each applicant

who had qualified, and a third list showing each applicant

who had actually been awarded a down-payment loan

and the amount of each loan awarded.

On

December 29, this author placed a records request to Mayor Lee

asking for a list of the first and last names, job classification

codes, and City Department of each applicant who had applied

for assistance under the Prop. “C” down-payment loan

assistance program once the program began accepting applications

in August 2013. Also requested was a second list of each applicant

who had qualified, and a third list showing each applicant

who had actually been awarded a down-payment loan

and the amount of each loan awarded.

The next day, Eugene Flannery, an Environmental Compliance Manager in the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development, responded indicating his office needed to consult with other City departments before it could respond. On January 13, Flannery finally provided an initial list showing that of the 12 employees whose names had been drawn from a lottery, eight were firefighters, one was a Sheriff’s Department employee, and three were police officers, but he neglected to include any information about the loan amounts actually awarded.

Flannery withheld the names of the City employees who applied for, qualified for, or were awarded assistance under the DLAP program. He claimed that for reasons of privacy, the City closely guards employee’s home addresses and the “general rule” is that the City does not disclose them to the public, ignoring the fact that the records requested had not asked for home addresses.

[This is notable, since later, on March 19, Flannery finally released the non-first responders DLAP program manual, which clearly stipulates that the names of DLAP recipients are public records, and the loan applications and all communications involved with the Mayor’s Office of Housing concerning the loans, are disclosable public records.]

Then on April 9, Flannery again refused to provide the names of the four first responders who have received DLAP loans to date, but he provided no legal citation to justify the withholding of public records.

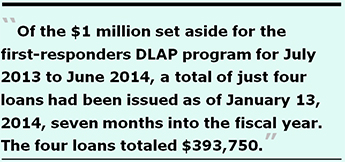

On

January 22, Flannery provided a second version of his list, which

indicated two of the “firefighters” are actually paramedics,

and then included loan amounts. Shockingly, of the $1 million

set aside for the first-responders DLAP program for July 2013

to June 2014, a total of just four loans had been issued as of

January 13, 2014, seven months into the fiscal year. The four

loans totaled $393,750, representing just 39 percent of the $1

million initially set aside in the program’s first-year budget.

The four loans represent just two percent of the full $20 million

appropriated to the Housing Trust Fund on July 1, 2013.

On

January 22, Flannery provided a second version of his list, which

indicated two of the “firefighters” are actually paramedics,

and then included loan amounts. Shockingly, of the $1 million

set aside for the first-responders DLAP program for July 2013

to June 2014, a total of just four loans had been issued as of

January 13, 2014, seven months into the fiscal year. The four

loans totaled $393,750, representing just 39 percent of the $1

million initially set aside in the program’s first-year budget.

The four loans represent just two percent of the full $20 million

appropriated to the Housing Trust Fund on July 1, 2013.

And notably, the non-first responders DLAP component had also been budgeted $1 million for FY 2013–2014, but as of March 2014 — nine months into the current fiscal year — the program had not even launched and ostensibly had no applicants (even from nurses or 9–1–1 dispatchers), and no awards had yet been made from the second $1 million DLAP program for non-first responders. It took the Mayor’s Office of Housing over 16 months to develop and issue the non-first responders DLAP manual between the time Proposition “C” was passed in November 2012 and when the manual was finally released on March 19, 2014. Wasted time during which no non-first-responder loans were offered, or issued.

On January 13, Flannery had responded to a first records request, saying that only 12 people had applied for the first responder DLAP loans, which came nowhere near close to the 45 public safety personnel the Chronicle had reported in July 2013 were “interested in applying.” Flannery indicated four of the loans had closed; six were “allocated” funds, but had ostensibly not been able to “secure” a property and had asked for and were granted extensions to accommodate their search for a home; and two were on some sort of waiting list. He indicated that when the extension period ended, applicants unable to secure a property would be removed from the reservation list and the freed-up slots would be made available on a first-come, first-served basis, with the two applications on the waiting list given priority over new, interested households.

When

asked on February 1 how his office would identify other employees

who might potentially want to bid on the vacated or unused lottery

drawing, Flannery started clamming up. He indicated two days later

on February 3 that his office would make announcements regarding

the remaining down payment assistance in the first-responders

program in March. Here we are at the end of March, and it’s

unknown whether any new announcements have been pushed out to

potentially-eligible public safety or first responder staff.

When

asked on February 1 how his office would identify other employees

who might potentially want to bid on the vacated or unused lottery

drawing, Flannery started clamming up. He indicated two days later

on February 3 that his office would make announcements regarding

the remaining down payment assistance in the first-responders

program in March. Here we are at the end of March, and it’s

unknown whether any new announcements have been pushed out to

potentially-eligible public safety or first responder staff.

Flannery did provide a sample notification letter, but creatively failed to answer a follow-up question about who the sample letter had been sent to, or when. And he creatively claimed a day later on February 4 that there were “no responsive records” to a request for a “waiting list” of those who sought first responder loans in FY 2013–2014. First, Flannery used the term “waiting list” several times in January. Then he said in February no waiting list exists. Which is it? He hasn’t explained.

When asked for program manuals for the overall Down Payment Assistance Loan Program required by Charter Section 16.110(d)(2) following passage of Prop. “C” in 2012, the manual for the “Housing Stabilization Program” required by Charter Section 16.110(d)(3), and any another other program manuals or policies and procedures for the Neighborhood Infrastructure Grant Program and the Affordable Housing Development program, Flannery provided four documents on February 14: A “Cal Homes” policies and procedure manual, a “Healthy Homes” write-up, a “Single-Family Tenant-Occupied Loan Program” write-up about providing affordable financing to rehabilitate one- to four-unit properties occupied by low- and moderate-income tenant households, and the first-responders DLAP manual.

While the Healthy Homes and rental rehabilitation programs are two of the 10 separate program components within the “Housing Stabilization Program,” Flannery provided no other information regarding the other eight sub-components. It appears that despite the 16 months since Prop. “C” passed in 2012, an over-arching manual for all 10 components of the Housing Stabilization Program may not have been developed yet, despite the Charter’s requirement.

As far as that goes, Flannery provided no manual for the Complete Neighborhood Infrastructure component, or the Affordable Housing Development component of the Housing Trust Fund.

And

Flannery provided no “manuals” or procedures regarding

stabilizing at-risk rent-controlled units, or the Mayor’s

plan announced two weeks earlier during his State-of-the-City

speech on January 17 promising to build only market-rate rental

units. What? No procedures to help “affordable” or low-income

renters at all?

And

Flannery provided no “manuals” or procedures regarding

stabilizing at-risk rent-controlled units, or the Mayor’s

plan announced two weeks earlier during his State-of-the-City

speech on January 17 promising to build only market-rate rental

units. What? No procedures to help “affordable” or low-income

renters at all?

Initial Two-Year Housing Trust Fund Budget

To his credit, Mr. Flannery did provide the initial two-year Mayor’s Proposed Budget for use of the Housing Trust Fund in FY 2013–2014 and FY 2014–2015 authored by the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development. It paints a disturbing picture.

It shows that for the first year, just $2 million — just 10 percent of the initial $20 million diverted to the Housing Trust Fund — would be split equally between the separate first responders and non-first responders DLAP program components. The Housing Stabilization sub-program was budgeted to receive 14.1 percent, or $2.8 million. The Neighborhood Infrastructure program was budgeted to receive just one percent, a paltry $200,000. “Program delivery” — ostensibly including personnel, “overhead,” and legal expenses — fared much better, at 5.8 percent, or $1.15 million of the initial $20 million.

Shockingly, fully 69 percent — $13.8 million — was budgeted for “affordable housing development,” the same Affordable Housing Development component for which Flannery provided no program manuals or write-ups. Nobody has explained what the Affordable Housing Development component will do — or how over two-thirds of the first $20 million deposited into the Housing Trust Fund in July 2013 will be used.

When the City starts kicking in the additional $2.8 million in FY 2014–2015 on July 1, 2014 in the second year on top of the first $20 million required by Prop. “C,” the allocation to each major sub-component shifts, ever so slightly. The non-first responders budget will double to $2 million (at the same time the initial two-year budget provides no increase to the $1 million set aside for first responders which will remain at a flat $1 million), so both DLAP components will rise to 13.2 percent of the $22.8 million; funding to the Housing Stabilization program will see a modest increase of just $300,000, dropping it to just 13.6 percent of the mix; the Neighborhood Infrastructure funding will quintuple from just $200,000 to a full million, jumping to 4.4 percent; and the Affordable Housing “Development” component will see a $700,000 increase to $14.5 million, but will drop to just 63.6l percent of the second-year budget.

Across

the first two-year budget of $42.8 million for all uses of the

Housing Trust Fund, this brings us to a two-year combined total

of:

Across

the first two-year budget of $42.8 million for all uses of the

Housing Trust Fund, this brings us to a two-year combined total

of:

Rocky Road of Performance

Data

from the City Controller’s Office and the Board of Supervisors

Budget and Legislative Analyst — Mr. Harvey Rose’s outfit

— paint a troubling picture of the Mayor’s Office of

Housing and Community Development.

Data

from the City Controller’s Office and the Board of Supervisors

Budget and Legislative Analyst — Mr. Harvey Rose’s outfit

— paint a troubling picture of the Mayor’s Office of

Housing and Community Development.

In response to a records request placed with the City Controller, it turns out that as of February 18, 2014 fully 92.8 percent — $17.5 million — of the total $20 million transferred from the General Fund to the Housing Trust Fund for its first year of funding remains unencumbered (unspent) fully nine months into the current 2013–2014 fiscal year.

Of the $1.15 million set aside for program delivery including personnel and legal expenses to administer the Trust Fund, fully 86 percent — $991,797 — remains unencumbered nearly nine months into the current funding cycle.

More shockingly, of the $20 million diverted from the General Fund to the Housing Trust Fund, the City Controller’s data shows that either the Board of Supervisors, the Controller’s Office, or the Mayor’s Budget Office had tinkered with the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development’s proposed budget submission for FY 2013–2014 by moving $1 million from loan assistance programs to “community-based organizational services.” The Community-Based Service budget line item has encumbered about 42 percent of its revised budget to date in the fiscal year (after the Board of Supervisors tinkered adjusting its budget), the sole program to have encumbered a significant portion of its budget.

Which “community-based services” may have been recipients of this encumbered largesse, is not yet known.

But

it stands in stark contrast to the Controller’s data that

shows not only that the line item index code for “loans issued

by the City” was reduced from $17.8 million to just $16.8

million, with the reduced $1 million apparently moved to “community-based

services,” but also that $16.4 million of the remaining $16.8

million for loans “issued by the city” remains unencumbered,

fully 97.6 percent of the funds the Controller said had been budgeted

for “loans.”

But

it stands in stark contrast to the Controller’s data that

shows not only that the line item index code for “loans issued

by the City” was reduced from $17.8 million to just $16.8

million, with the reduced $1 million apparently moved to “community-based

services,” but also that $16.4 million of the remaining $16.8

million for loans “issued by the city” remains unencumbered,

fully 97.6 percent of the funds the Controller said had been budgeted

for “loans.”

Not explained by the Controller’s Office is why the Mayor’s Office of Housing may have submitted a proposed budget listing five separate main components of the Housing Trust Fund, but the Controller’s “index codes” for FY 2013–2014 and FY 2014–2015 contained just two major categories for “community-based organizational services,” and “loans issued by the City,” as if “neighborhood infrastructure” and “affordable housing development” projects have no separate index code to track their programmatic costs and can just be lumped together in a single index code apparently labeled “loans issued by the City.”

And the Controller’s Office hasn’t explained whether the $13.8 million requested in the Mayor’s Office of Housing’s proposed budget earmarked for “Affordable Housing Development” in the first year (FY 2013–2014) has been rolled into a single line item for $16.4 million for “loans issued by the City.” The November 2012 voter guide made no mention of using any portion of the $20 million Housing Trust Fund for “Affordable Housing Development,” but here we have the Mayor’s Office of Housing’s budgeting $13.8 million in the first fiscal year towards that purpose, while the City Controller’s Office may have lumped any such expenditures into an index code designated as “loans.”

Affordable Housing Development “loans”? To whom are these loans being shopped to? No explanation has been forthcoming from Flannery, or his boss Olson Lee.

If the $13.8 million in “affordable housing development” loans in FY 2013–2014 are not being disbursed to either first-responder or non-first responder loan applicants, who are the “loans” being awarded to? Or will that money just be rolled over into a subsequent fiscal year and spent later?

Mr. Flannery, and his boss Olson M. Lee (not a relative of Mayor Ed Lee), aren’t saying. And they haven’t provided a program manual or write-up describing any program to underwrite “affordable housing development” loans, terms of such loans, repayment provisions, or qualifications required to even apply.

Comparing

the Mayor’s Office of Housing’s Proposed Budget for

the Housing Trust Fund against the City Controller’s

line-item index codes, reveals a host of unanswered questions.

Comparing

the Mayor’s Office of Housing’s Proposed Budget for

the Housing Trust Fund against the City Controller’s

line-item index codes, reveals a host of unanswered questions.

Take, for example, public records obtained from both the Mayor’s Office of Housing and the Controller’s Office after this article was submitted for publication.

Different public records show that for the two-year budget cycle for FY 2014–2015 and FY 2015–2016 now being hashed out at City Hall for adoption July 1, 2014, that although the Office of Housing had requested $14.87 million in FY 2015–2016 for the so-called “Affordable Housing Development” component, the City Controller’s Office is now showing that component has been increased to $17.3 million, a $2.4 million increase over what had been requested by the Housing Office.

To do that, the City Controller’s data is reporting the requested $2 million in the second year for the “Neighborhoods Infrastructure” has been reduced by half, to $1 million. Similarly the City Controller’s data shows that the $3 million requested for “Small Site Acquisition/Rehab” has been reduced by one-third, to $2 million. Overall, the Controller’s data shows the “Housing Stabilization” component has been reduced from the requested $4.45 million to $3.1 million, with the difference being squirreled away to fatten up “Affordable Housing Development,” which will apparently take the form of “loans,” but loans to whom, when, and for what purpose remains unexplained by Flannery and Olson Lee.

Again, it’s unclear whether it was the City Controller, the Board of Supervisors, or the Mayor’s Budget Office that moved funds around in the Mayor’s Office of Housing’s proposed budget.

When Harvey Rose Speaks, People Listen

In a development unrelated to the Housing Trust Fund per se, but closely related to the “affordability crisis” that has resulted from Mayor’s Lee’s focus on luring tech sector “jobs,” and that has resulted in massive displacement in San Francisco, Harvey Rose — the Board of Supervisors Budget and Legislative Analyst — has weighed in, however unintentionally, on performance of the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development.

In

February 2014, Rose submitted an analysis to the Board of Supervisors who were

considering a $2 million increase to an initial proposal to divert

$2.5 million from the City’s General Fund Reserve account

to fund a new “Non-Profit Rental Stabilization Program,”

increasing the proposal to $4.5 million.

In

February 2014, Rose submitted an analysis to the Board of Supervisors who were

considering a $2 million increase to an initial proposal to divert

$2.5 million from the City’s General Fund Reserve account

to fund a new “Non-Profit Rental Stabilization Program,”

increasing the proposal to $4.5 million.

Rose noted such a decision might be premature, since the criteria for awarding stabilization funds to individual nonprofit organizations, any limitations on use of the funds, limits on the amount of funds to be awarded, and “administrative and selection procedures” had not yet been decided, and won’t be until after a planned report from a so-called “Nonprofit Displacement Work Group” is completed and presented, presumably on April 11, 2014.

Rose claimed it was simply a “policy matter” for the Board to consider increasing the raid of the General Fund Reserve account, reducing General Fund reserves from $44 million to just $40 million, which the San Francisco Examiner later creatively titled a news article as being a “gift” to the City, albeit being a raid of the City’s reserve coffers, not a philanthropic “gift.”

Rose

claimed this, after first admitting that way back in 2000,

the Board of Supervisors had approved two ordinances to appropriate

$1.5 million from the City’s General Fund Reserve to provide

rent subsidies to nonprofit arts organizations in immediate danger

of being evicted or displaced by rent increases.

Rose

claimed this, after first admitting that way back in 2000,

the Board of Supervisors had approved two ordinances to appropriate

$1.5 million from the City’s General Fund Reserve to provide

rent subsidies to nonprofit arts organizations in immediate danger

of being evicted or displaced by rent increases.

Rose reported on February 26, 2014, that the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development claims overall expenditures, including administrative costs of the arts rental assistance program, are “not currently available.”

Wait! What? The Mayor’s Office of Housing has no information available at all about how $1.5 million may (or may have not) have been spent over a 14-year period?

Apparently, Mr. Brian Cheu, Director of Community Development in the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development advised Rose’s team that “approximately” 12 grants for rental subsidies were provided under the arts rental assistance program during an unspecified time frame. More apparently, “approximately” was as close as Cheu could get, which Rose appears to have accepted and the Board of Supervisors appear to have later swallowed at face value.

A million-and-a-half dollars vanish over 14 years, and nobody knows where, or how?

Rose’s report provided to the Board of Supervisors noted that Mr. Cheu in the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development advised Rose that there was also “no information” about the $500,000 portion of the rent subsidies to nonprofit service and advocacy organizations. How’s that for bloviated (as in empty) record-keeping?

Surprisingly, Rose uncharacteristically included in his report a damning statement, saying, “… such that it appears that the City may have never implemented this portion of the program.” Really? No implementation? And no records? Where’s the money?

With record keeping like that in the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development, what else are they declining to disclose — or hiding? Perhaps its director, Olson M. Lee, knows.

More “Office of Housing” Nonsense

As recently as March 17, Mayor Ed Lee’s director of the Mayor’s Office of Housing, Olson M. Lee, was quoted in a San Francisco Chronicle article saying that the Mayor’s doubling of the down-payment assistance loans to $200,000, from $100,000 would be “a lot more helpful.” Olson Lee was reportedly referring to market-rate housing.

For the first time, we have an admission via the Chronicle that the loans appear to be reserved for buyers of “market rate” homes, not “below market rate” or “affordable homes” buyers, and then only for those earning up to 120 percent of AMI.

The Chronicle’s March 17 article noted Mayor Lee had proposed a $15 million increase in “new contributions” from the city’s “main spending account” [would that be the City’s General Fund?] should be added over the next five years, ostensibly to the non-first responders DLAP funding.

After the Chronicle reported that the maximum DLAP award would be increased to $200,000, and that $15 million in new contributions might accrue to the Housing Trust Fund, imagine this tenacious reporter’s surprise after placing yet another records request.

Asked whether the proposed number of loans to be issued would be reduced from ten $100,000 loans to only five $200,000 loans, MOHCD director Olson Lee again clammed up, allowing Flannery’s non-answers to go unanswered a second time.

Because

the second and third years of the first responder DLAP component

remain flat-funded at $1 million annually, but the loan ceiling

is raised to $200,000, this may portend that with the increase

to $200,000 loans, only five loans annually may happen in Year

2 and Year 3, not the ten loans anticipated at $100,000.

Because

the second and third years of the first responder DLAP component

remain flat-funded at $1 million annually, but the loan ceiling

is raised to $200,000, this may portend that with the increase

to $200,000 loans, only five loans annually may happen in Year

2 and Year 3, not the ten loans anticipated at $100,000. Let’s

do simple math. One hundred households who could each qualify

for $200,000 would require the Housing Trust Fund to have $20

million available in these two DLAP component budgets during

the next five years.

Let’s

do simple math. One hundred households who could each qualify

for $200,000 would require the Housing Trust Fund to have $20

million available in these two DLAP component budgets during

the next five years.Asked of Olson Lee on March 18 whether the Examiner’s article was reporting a new $15 million increase over and above the already-pledged $20 million-plus annual allocation increases, or whether the so-called “new” $15 million increase is simply the same dollar amount increase of $2.8 million previously authorized to be accumulated during the same five-year period, Flannery inappropriately answered with a one-word “No,” to what was an either-or question.

So

it was unclear whether the Mayor plans to add $15 million to the

Housing Trust Fund in new money beginning July 1, 2014 beefing

up the pot, or whether his social media spin meisters are merely

double-counting the annual $2.8 million increase in each of the

next five years already required by Prop. “C” that will

yield almost the same $15 million.

So

it was unclear whether the Mayor plans to add $15 million to the

Housing Trust Fund in new money beginning July 1, 2014 beefing

up the pot, or whether his social media spin meisters are merely

double-counting the annual $2.8 million increase in each of the

next five years already required by Prop. “C” that will

yield almost the same $15 million.

When Olson Lee was asked about Flannery’s inappropriate answer of “No” to a clear either-or question, Mr. Lee had his deputy, Maria Benjamin, Director of Homeownership and Below-Market Rate Programs, reply on his behalf.

Ms. Benjamin further clamed up, saying that the Brown Act, California’s Public Records Act, and Proposition 59 — and by extension, San Francisco’s Sunshine Ordinance — only require public agencies to provide existing documents. Not explanations.

In other words, Ms. Benjamin, Mr. Flannery, and Mr. Olson Lee collectively appear to be unwilling to simply answer either-or questions, implying they will produce only specific documents requested, not any explanations to simple, specific questions involving elaboration about the Housing Trust Fund.

But the second two-year Housing Trust Fund budget this columnist received just as the Westside Observer was going to press for this edition, shows that through Fiscal Year 2015–2016 there is no new portion of a $15 million increase in the next two-year budget, suggesting that the $15 million increase being creatively spun as “new money” by the Mayor’s press staff is actually the same pot of money from the $2.8 million increase times five years already budgeted.

So

much for the “trust” side of the “in the public

trust” equation.

So

much for the “trust” side of the “in the public

trust” equation.

Instead, we appear to have an Office of Housing and Community Development hell bent on hiding from the public, just how it is spending hundreds of millions of dollars meant to spur affordable housing development.

Housing in the Wild, Wild West

Although the mainstream media have reported Mayor Lee wants to issue up to 2,500 down-payment assistance loans of up to $200,000 each loan over the next six years — which may require funding as high as five-hundred million (yes, a half-billion in “loans” — nobody’s talking about the fact that issuing just four loans per year (as the City did in the first year of the program), it will take 2,500 applicants a total of 625 years to perhaps receive loans, given the glacial speed of the Mayor’s Office of Housing.

Bumping it up to even forty $200,000 loans per year will take the Mayor’s Office of Housing a full 62.5 years to issue 2,500 loans, not six years. After all, if the Mayor really plans to issue 2,500 down-payment-assistance loans during the next six years, his Office of Housing will need to process, approve, and issue 417 loans each year, not four each year.

The

Mayor would have to quickly come up with $500 million within six

years that he hasn’t explained to the electorate where such

inflated spending will come from. And he may have to explain why

the mainstream media have been reporting that DLAP loans appear

to be restricted only to market-rate homes.

The

Mayor would have to quickly come up with $500 million within six

years that he hasn’t explained to the electorate where such

inflated spending will come from. And he may have to explain why

the mainstream media have been reporting that DLAP loans appear

to be restricted only to market-rate homes.

The Mayor’s Seven-Step Plan reported in the media in January claims that 30 percent of the total housing goal would be reserved for lower-income residents, for example a family of four earning less than $50,000 annually. There’s no mention in the program manuals provided by Flannery that the Housing Trust Fund will dedicate 30 percent of its total funding for four-person households earning less than $50,000 annually.

The media also reported in January that 25 percent of Lee’s Seven-Step Plan housing goals targets middle income families of four earning between $100,000 and $150,000.

That

brings the lower- and middle-income beneficiaries to just 55 percent

of the housing goals. Creatively, the major media made no mention

of the remaining 45 percent of the housing goals in Lee’s

Seven-Step Plan.

That

brings the lower- and middle-income beneficiaries to just 55 percent

of the housing goals. Creatively, the major media made no mention

of the remaining 45 percent of the housing goals in Lee’s

Seven-Step Plan.

Presumably, fully 45 percent of the remaining housing goals will be targeted to four-person (or other) families earning more than $150,000 annually, presumably to upper-income residents.

In fact, there’s no mention at all in the documentation Flannery provided — and no mention in the enabling legislation in the legal text of Proposition “C” passed by voters in 2012 — on how the Housing Trust Fund may be permitted to split percentages between lower-, middle-, and upper-income residents.

Five years ago, the San Francisco Bay Guardian carried a story titled “Lennar’s housing scam, redux,” reporting misrepresented promises by Lennar to build 32 percent affordability into its 10,500 homes being built in Bayview Hunter’s Point. Observers noted back then that the main rationale for building so much market-rate housing is callously for the property taxes they will bring to the City’s coffers.

This reporter also noted back in May 2008 that there was nothing in the legal text of the 2009 Proposition “G” ballot measure awarding Lennar the development rights in the Bayview that guarantees any precise percentage of housing that will be designated as “affordable.” Indeed, Lennar’s development plan for Parcel “A” in the Bayview had initially promised low-income rental units. Lennar single-handedly changed the composition of the first 1,600 units to be built, all of which will be at market rate — with no low-income rental units. We’ve been warned: Lennar may end up building only market rate units.

The first 1,600 units are expected to each sell for San Francisco’s then median price of $836,000 in 2008 dollars. That will net Lennar $1.38 billion in homes and condos on Parcel A. Every day of delay by Lennar is designed to drive up the median prices of housing in order to increase Lennar’s profits.

Given apparent early failures of the Mayor’s Housing Trust Fund, one wonders whether the Bay Guardian might now, five years later, write another article, perhaps titled “The Mayor’s housing scam, redux.”

After

all, the 2012 voter guide indicated that the Housing Trust Fund

would include “uses” for rental housing. Given that

approximately 64 percent of San Franciscans are renters, it’s

troubling that the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community

Development’s first-year proposed budget for FY 2013–2014

and FY 2014–2015 included just $200,000 (or of $20 million)

for rental eviction defense, and nothing from the Housing Trust

Fund itself for rental unit rehabilitation. In the second year

in FY 2014–2015, the Housing Trust Fund is budgeting to add

$200,000 for rental unit rehabilitation, and will double that

to $400,000 in FY 2015–2016.

After

all, the 2012 voter guide indicated that the Housing Trust Fund

would include “uses” for rental housing. Given that

approximately 64 percent of San Franciscans are renters, it’s

troubling that the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community

Development’s first-year proposed budget for FY 2013–2014

and FY 2014–2015 included just $200,000 (or of $20 million)

for rental eviction defense, and nothing from the Housing Trust

Fund itself for rental unit rehabilitation. In the second year

in FY 2014–2015, the Housing Trust Fund is budgeting to add

$200,000 for rental unit rehabilitation, and will double that

to $400,000 in FY 2015–2016.

Adding the $600,000 the Housing Trust Fund has budgeted for rental eviction defense across the three-year budget periods between FY 2013–2014 and FY 2015–2016 to the total of $600,000 budgeted in the second and third years for rental unit rehabilitation, the Housing Trust Fund appears to have budgeted just $1.2 million — just 1.75 percent — for any sort of rental assistance, out of the total $68.4 million that will be appropriated during the first three years of the Trust Fund budgets. In a City where over 64 percent of the residents are renters.

Despite City Hall’s bleating that the Mayor would beef up rental eviction defense funding (following the 2013 Ellis Act eviction of Poon Heung Lee and Gum Gee Lee and their disabled daughter debacle), the eviction defense and prevention budget in the Housing Trust Fund’s budget appears to be flat funded at $200,000 in each of the first three years. How many more Poon Heung and Gum Gee Lee evictions will there be, before the eviction defense fund is actually beefed up, not simply flat-funded?

This is despite a San Francisco Examiner article on October 1, 2013 that Mayor’s Office of Housing had increased funding for tenant counseling services “by 63 percent, to $700,000, bringing the total to more than $2.3 million in eviction prevention services.” How do you inflate just $600,000 in Housing Trust Fund monies in public-record budgets for renter eviction defense programs, into $2.3 million? Is this more bloviated bread and fish, and infused wine?

Playing Voters for Suckers

Typically, San Francisco voters are a pretty savvy group. Voters appear to have been snookered in 2012.

After

all, we passed a ballot measure in March 2002 creating the Citizens

General Obligation Bond Oversight Committee to monitor use of

hundreds of millions in general obligation bonds earmarked for

a variety of capital infrastructure improvement projects. Voters

also passed the same year in November, a measure creating a Revenue

Bond Oversight Committee to monitor issuance of Revenue Bonds

for the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, given the billions

at stake in various Hetch Hetchy, water system, and sewage system

projects.

After

all, we passed a ballot measure in March 2002 creating the Citizens

General Obligation Bond Oversight Committee to monitor use of

hundreds of millions in general obligation bonds earmarked for

a variety of capital infrastructure improvement projects. Voters

also passed the same year in November, a measure creating a Revenue

Bond Oversight Committee to monitor issuance of Revenue Bonds

for the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission, given the billions

at stake in various Hetch Hetchy, water system, and sewage system

projects.

Although both oversight committees created in 2002 have had only marginal success, riddled with political appointees to both bodies, there is at least a perception of oversight. Not so with the Housing Trust Fund, which has no oversight.

Voters were played for suckers when Proposition “C” was put before them creating the Mayor’s Housing Trust Fund. Without clearly being advised that the Housing Trust Fund would be managing upwards of $1.3 billion for a whole host of housing programs, voters weren’t offered any opportunity to have an Oversight Committee established to monitor use of the Housing Trust Fund. Not only do voters have no oversight of use of the Housing Trust Fund, they also have no oversight of the $1.34 billion in cuts that will be made to the City’s discretionary General Fund that will then be diverted to fund the Housing Trust Fund.

Did Flannery, Olson Lee, or someone else at City Hall suddenly realize that bloviating 2,500 loans was just too far over the top, even using spin control, and that’s when they de-blovitated expectations by re-christening 100 DLAP loans as the new 2,500 DLAP loans three months later?

This just adds insult to injury, since not only have voters been excluded from overall decision-making on how the Housing Trust Fund’s money will be spent, they also appear to have been excluded from any decision-making regarding who the eligible applicants will be. They’ve also been excluded from any decision-making regarding how the trust funds will be split between low-, middle- and upper-income applicants, among other decision-making exclusions.

Although we’re told checks and balances of government are necessary to defend our democracy, there’s no provision of any sort for checks-and-balances over this Housing Trust Fund. How do you provide the citizenry with trust regarding Housing Trust Fund trustees, when there are no checks or balances over the trustee’s decision-making?

If I were a betting man, I’m not convinced I’d wager the Mayor’s seven-point “housing affordability” plan will come to fruition. P.T. Barnum — or whichever con man came up with the aphorism — provided fair warning about not being played for a sucker.

Not One Penny for “Old Friends”

While

the Board of Supervisors and the Mayor are scrambling to divert

$4.5 million from the City‘s General Fund Reserve account

to rescue non-profit organizations facing out-of-county displacement

due to the hot housing market, and are trying to entice public

safety first-responders to snap up $200,000 down-payment assistance

loans hoping to lure them into moving back into the City, the

City, meanwhile, is not lifting a finger or spending any of the

Housing Trust Fund in order to help our “Old Friends”

— seniors, the elderly, and people with disabilities —

being forced into out-of-county displacement (read: discharged

from Laguna Honda Hospital or SFGH and dumped out-of-county, or

are being “diverted” from admission to LHH and are also

diverted out-of-county.

While

the Board of Supervisors and the Mayor are scrambling to divert

$4.5 million from the City‘s General Fund Reserve account

to rescue non-profit organizations facing out-of-county displacement

due to the hot housing market, and are trying to entice public

safety first-responders to snap up $200,000 down-payment assistance

loans hoping to lure them into moving back into the City, the

City, meanwhile, is not lifting a finger or spending any of the

Housing Trust Fund in order to help our “Old Friends”

— seniors, the elderly, and people with disabilities —

being forced into out-of-county displacement (read: discharged

from Laguna Honda Hospital or SFGH and dumped out-of-county, or

are being “diverted” from admission to LHH and are also

diverted out-of-county.

Up to $1.34 billion is being promised for a wide variety of housing under the Housing Trust Fund. But not a penny of it is being earmarked to help our Old Friends continue residing as San Franciscans, in-county. Why not?

This, from a Mayor who started his career in public service as an advocate for affordable housing and the rights of immigrants and renters at the San Francisco Asian Law Caucus, including the elderly. In 1989, Lee was subsequently appointed by then-Mayor Art Agnos as the City’s first investigator under the city’s Whistleblower Ordinance. Lee has led a charmed life of subsequent appointments to various City departments, then was crowned Mayor. Providing affordable housing to our Old Friends may no longer be his primary focus — or of any interest to him.

After

all, Christine Falvey, the Mayor’s spokesperson, intoned

in the Chronicle on April 8, that “It’s very

well known that the Mayor’s approach is to do things with people, not to

them” [emphasis added]. Falvey was spinning the myth that

Lee is the “consensus mayor.”

After

all, Christine Falvey, the Mayor’s spokesperson, intoned

in the Chronicle on April 8, that “It’s very

well known that the Mayor’s approach is to do things with people, not to

them” [emphasis added]. Falvey was spinning the myth that

Lee is the “consensus mayor.”

Just ask 9-1-1 dispatchers how much they’ve gained so far in consensus concerning “housing affordability” under the Mayor’s Housing Trust Fund. Has the Mayor been doing “to,” not “with,” with dispatchers, without their consensus?

Ask your Old Friends the same questions. Their answers may go a long way towards explaining why our Old Friends are being driven out-of-county.

Monette-Shaw is an open-government accountability

advocate, a patient advocate, and a member of California’s

First Amendment Coalition. Feedback: monette-shaw@westsideobserver.com.

The print edition of this Westside Observer article was a condensed

version; this is the expanded version.

Postscript

On April 9, the Chronicle published an article reporting that District 6 Supervisor Jane Kim is pushing to boost affordable housing. She has introduced legislation requiring developers to justify their projects to the City Planning Commission if affordable housing dips below 30 percent of housing in her district. She believes that at least 30 percent of new construction should be earmarked ”affordable,” to prevent further displacement and help San Franciscans who want to live in the City have a fighting chance to stay here.

The

Chronicle article quotes Gabriel Metcalf, the Executive

Director of the extremely conservative non-profit urban planning

agency, SPUR. Metcalf reportedly said, “The only limits on

affordable housing are the subsidies to pay for it [sic]. Policymakers

should be focused on coming up with more subsidies.” (As

an aside, SPUR has been erroneously described recently in the

mainstream media as being a “watchdog” agency, which

it is not. It is an arch-conservative urban planning outfit that

meddles in City planning and policymaking, and is a strong advocate

for market-rate projects for its developer allies.)

The

Chronicle article quotes Gabriel Metcalf, the Executive

Director of the extremely conservative non-profit urban planning

agency, SPUR. Metcalf reportedly said, “The only limits on

affordable housing are the subsidies to pay for it [sic]. Policymakers

should be focused on coming up with more subsidies.” (As

an aside, SPUR has been erroneously described recently in the

mainstream media as being a “watchdog” agency, which

it is not. It is an arch-conservative urban planning outfit that

meddles in City planning and policymaking, and is a strong advocate

for market-rate projects for its developer allies.)

Really? More subsidies? After voters (however unwittingly) approved at the ballot box diverting $1.34 billion in General Fund cuts over the next 30 years into the Mayor’s Housing Trust Fund — which is budgeting upwards of 66 percent of its funds in an “Affordable Housing Development” sub-component — how much more in “subsidies” does Mr. Metcalf expect “policy makers” to cough up? While he claims that the “only limit” to affordable housing is a lack of “subsidies,” there are plenty of limits and roadblocks being introduced by the Mayor’s Office of Housing.

Given that the Housing Trust Fund is heavily skewed toward only market-rate housing — and fully 45 percent of which the Mayor’s Office of Housing claims may be reserved for upper-income earners making more than $150,000 annually — why does Metcalf believe that these upper-income applicants just need more “subsidies” created by “policymakers”?

Metcalf ignores that once General Funds are deposited into the Housing Trust Fund, all accountability and oversight of how the funds will be used for affordable housing all but vanishes. He also ignores that the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development has “sole discretion” to administer the fund. Take for example the 16-month delay between passage of Proposition “C” in November 2012 and the March 2014 release of the non-first responders DLAP program manual. The Mayor’s Office of Housing limited access to affordable housing for 16 months dragging its feet developing the program guidelines.

In a separate Chronicle article on the same day regarding Ellis Act evictions, Mayor Lee tried to bolster the call in his State-of-the-City speech last January to build or rehabilitate 30,000 homes over the next 30 years. His proposal in January contained scant information on whether he was talking 30,000 “homes” for purchase, or whether he was planning for some mix of the 30,000 to be rental units.

The Mayor now claims in the Chronicle article that while adding more housing must be part of the plan, “part of our strategy must be to protect existing [rental] units.” There’s just one small problem with the Mayor’s new claim.

And that’s that the Housing Trust Fund does next to nothing to protect — let alone add any new — rental units that are “affordable.” And so far, Mayor Lee hasn’t proposed or created a comparable “Rental Trust Fund” — akin to the Housing Trust Fund — endowed with $134 billion.

Although

the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Develop claims

it’s budgeting for “Affordable Housing Development,”

and the Mayor touts his “affordability agenda,” the

City Controller — in charge of the City’s purse strings

— deposits the affordable housing development funds diverted

from the General Fund into a sub-account titled the “Housing

Development Pool,” which remains sub-titled as a “Loans

Issued by the City” component program.

Although

the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Develop claims

it’s budgeting for “Affordable Housing Development,”

and the Mayor touts his “affordability agenda,” the

City Controller — in charge of the City’s purse strings

— deposits the affordable housing development funds diverted

from the General Fund into a sub-account titled the “Housing

Development Pool,” which remains sub-titled as a “Loans

Issued by the City” component program.

Notice that the word “affordable” went missing by the City Controller. Also notice how Flannery and the Mayor’s Office of Housing appear to have no program manual describing how the “pooled money” will be divvied up.

As observers know, once money is “pooled,” it can then be diverted (and often is) to almost any purpose, including upper-income households, and perhaps only for market-rate — not “affordable” — housing, not assistance to renters.

Given that there is no oversight body for the Housing Trust Fund, we’ll have to see how the Mayor’s Office of Housing, in collaboration with the City Controller’s Office, ends up allocating funds in the housing “pool,” and to what types of housing.

Over the next six years, as the City drags its heels on the Housing Trust Fund, how many more thousands of San Franciscans will no longer be living in the City, displaced by the bait and switch in the Mayor’s “affordability agenda” and the glacial inaction in the Mayor’s Office of Housing?