Westside Observer

Westside Observer May 2015 at www.WestsideObserver.com

San Francisco’s Housing Crisis

Housing Withers on the Vine

Article in Press Printer-friendly

PDF file

Westside Observer

Westside Observer

May 2015 at www.WestsideObserver.com

San Francisco’s

Housing Crisis

Housing Withers

on the Vine

by Patrick Monette-Shaw

You’d figure that a Mayor who wants to entice voters into approving a $250 million housing bond next November — and re-electing him — would be forthcoming responding to requests for records of his housing accomplishments.

You’d be wrong. This Mayor’s Office of Housing keeps thumbing its nose at reasonable records requests. This can only be seen as a new definition of hubris: Expecting voters to pass a bond measure and re-elect the Mayor, but totally unwilling to provide basic records.

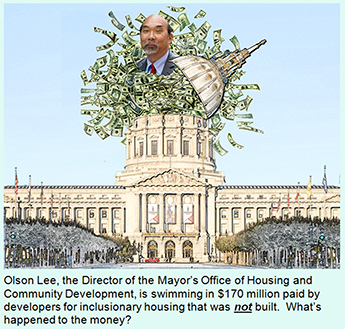

You know San Francisco’s affordable housing production faces a severe crisis when almost half of voters disapprove of Mayor Ed Lee’s performance.

A poll conducted by Public Policy Polling between April 2 and April 5 for Larry Bush — an aide to former Mayor Art Agnos, a founding member of Friends of Ethics, a former San Francisco Examiner columnist, proprietor of CitiReport.com, and a member of San Francisco’s 2013–2014 Civil Grand Jury — concluded that 46 percent of 569 voters disapprove of how Mayor Ed Lee is running the City, and only 38 percent of survey respondents approve of the job Lee is doing.

One probable reason

for the Mayor’s high disapproval rating may be directly tied

to his Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development

(MOHCD), which is notorious for its lack of transparency.

One probable reason

for the Mayor’s high disapproval rating may be directly tied

to his Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development

(MOHCD), which is notorious for its lack of transparency.

This article first explores four documents totaling 268 pages: The 2014 Civil Grand Jury report on MOHCD, the Planning Department’s 2014 Housing Inventory Report, MOHCD’s belated Annual Report for FY 2012–2013 and 2013–2014, and the City Controller’s Biennial Development Impact Fee Report for FY 2012–2013 and 2013–2014. Second, it then explores some relevant concerns about the state of housing in San Francisco.

Emperor’s New Clothes: Four Opaque Reports

To understand the wither of housing being built in San Francisco you need to wade through reading at least four reports to piece the cookie crumbs together.

In November 2014, voters passed Proposition “K,” the Affordable Housing declaration of policy that Supervisor Jane Kim agreed to water-down with the Mayor that replaced her proposed November 2014 ballot measure for affordable housing. The declaration of policy regurgitated the Mayor’s January 2014 State of the City speech in which he pledged to construct or rehabilitate at least 30,000 homes by the year 2020, claiming 50% of the housing will be affordable for middle-class households, and at least 33% would be affordable for low- and moderate-income households.

Those goals were already the Mayor’s stated policy goals, so the declaration of policy was unnecessarily redundant. Supervisor Kim was simply snookered by the Mayor.

As City Controller

Ben Rosenfield noted in the 2014 Voter Guide for Prop. “K”:

As City Controller

Ben Rosenfield noted in the 2014 Voter Guide for Prop. “K”:

No declaration of policy can trump the City Charter or the City’s budgeting processes.

Civil Grand Jury Report

In June 2014, San Francisco’s 2013–2014 Civil Grand Jury released a report titled “The Mayor’s Office of Housing: Under Pressure and Challenged to Preserve Diversity.” In many ways, the Grand Jury report is a damning indictment of the lack of transparency at the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development (MOHCD).

The Grand Jury report

focused its research on the 2014 Affordable Housing goals Mayor

Lee announced in his January 2014 State of the City speech. The

Grand Jury was interested in learning whether the housing targets

are achievable, whether there is sufficient transparency so the

public can accurately assess whether Affordable Housing objectives

are being met, and whether fairness is being applied when Affordable

Housing units become available for occupancy.

The Grand Jury report

focused its research on the 2014 Affordable Housing goals Mayor

Lee announced in his January 2014 State of the City speech. The

Grand Jury was interested in learning whether the housing targets

are achievable, whether there is sufficient transparency so the

public can accurately assess whether Affordable Housing objectives

are being met, and whether fairness is being applied when Affordable

Housing units become available for occupancy.

Among its conclusions, the Jury noted that proper public notification should be served for any diversion of Housing Trust Fund uses approved by voters in the November 2012 Proposition “C.” The Jury was apparently worried that Housing Trust Funds might be diverted to provide additional financing for the successor agency to San Francisco’s Housing Authority and used to rebuild public housing, rather than affordable housing that voters were promised.

Another of the Jury’s conclusions was that “Below Market Rate (BMR) programs administered by MOHCD place a costly and time-consuming burden upon developers and property agents, which may discourage outreach and fair access.” The Grand Jury noted that MOHCD’s communications with the public, including “the MOHCD Annual Report, quarterly reports of [housing being developed in] the housing pipeline, Affordable Housing achievement data, funding data and operational metrics are in the public interest but are not easily found nor produced with any regularity.”

The Jury found MOHCD had not issued an Annual Report since 2009. This suggests that whomever in City Hall is tasked with tracking whether all City departments are issuing their annual reports on time — that is, annually — has been asleep at the wheel for at least the past five years. As an aside, how many other City departments fail to publish annual reports each year? Of note, within nine months of the Grand Jury’s report, MOHCD recently got around to issuing its combined Annual Report for 2012–2013 and 2013–2014.

Unfortunately, the

Civil Grand Jury got it wrong on at least two points. First, among

other proposals to increase and preserve the City’s housing

stock, the Jury inappropriately recommended “requiring that some portion of

the City Employees’ Retirement System help finance Affordable

Housing projects as a local social investment strategy.”

This is simply wrong. Pension funds are there for the sole use

of providing retirement benefits for retirees and City employees

who are required to contribute up to 13% of their current income

towards their eventual retirement. The Pension Fund is held in

trust as a Trust Fund for retirees, not as a fund to be tapped

to fund housing projects.

Unfortunately, the

Civil Grand Jury got it wrong on at least two points. First, among

other proposals to increase and preserve the City’s housing

stock, the Jury inappropriately recommended “requiring that some portion of

the City Employees’ Retirement System help finance Affordable

Housing projects as a local social investment strategy.”

This is simply wrong. Pension funds are there for the sole use

of providing retirement benefits for retirees and City employees

who are required to contribute up to 13% of their current income

towards their eventual retirement. The Pension Fund is held in

trust as a Trust Fund for retirees, not as a fund to be tapped

to fund housing projects.

Second, in discussing challenges facing MOHCD, the Jury wrongly noted that the Housing Trust Fund — which I’ve reported will divert $1.3 billion to $1.5 billion from our General Fund over the next 30 years — “may need to provide stabilization funding to the Housing Authority for emergency repairs” [to public housing projects]. Later in its report, the Grand Jury wrote:

Clearly worried about diverting HTF funds to Housing Authority “Re-envisioning” projects — given the Jury’s acknowledgement that the City Charter provides that MOHCD has sole discretion on HTF disbursements — the Jury then cautioned that the City’s Administrative Code only requires that MOHCD report to the Board of Supervisors every fifth year, beginning in 2018, five years after the initial FY 2013–2014 $20 million HTF allocation.

By the time the Board of Supervisors holds its first hearing from MOHCD in 2018, MOHCD will have been handed a total of $128 million into the Housing Trust Fund from the City’s General Fund to use at its sole discretion during its first five years. Given MOHCD’s dubious track record, the Board of Supervisors needs to legislatively reduce the five-year period to two years, and schedule its first hearing in 2015.

As I wrote in April

2014, voters were told in 2012 that the Housing Trust Fund would

be used to 1) Create, acquire, or rehabilitate rental and home

ownership, including acquisition of land, 2) Fund $15 million

for down-payment loan assistance programs for public safety “first

responders” and other non-first-responders, 3) Fund another

$15 million in assistance to reduce the risk of loss of housing

and to make their homes safer, more accessible, energy efficient

or more sustainable in a Housing Stabilization Fund, 4) Accelerate

the build-out of public realm infrastructure needed to support

increased residential density, and 5) Allocate an amount sufficient

to cover administrative costs of the Trust Fund, including legal

and personnel costs.

As I wrote in April

2014, voters were told in 2012 that the Housing Trust Fund would

be used to 1) Create, acquire, or rehabilitate rental and home

ownership, including acquisition of land, 2) Fund $15 million

for down-payment loan assistance programs for public safety “first

responders” and other non-first-responders, 3) Fund another

$15 million in assistance to reduce the risk of loss of housing

and to make their homes safer, more accessible, energy efficient

or more sustainable in a Housing Stabilization Fund, 4) Accelerate

the build-out of public realm infrastructure needed to support

increased residential density, and 5) Allocate an amount sufficient

to cover administrative costs of the Trust Fund, including legal

and personnel costs.

Voters were not told in 2012 before they cast ballots that the Housing Trust Fund would be used for emergency repairs of Housing Authority properties.

The Jury’s report noted its policy concerns for affordable housing parity and fair distribution of housing built for all income tiers. Looking at it by household income as a percentage of AMI, the Jury noted in Table 1 that the City achieved 113% of market rate housing (those earning greater than 120% of Area Median Income, or AMI) between 2007 and 2014 identified in the Regional Housing Needs Allocation goals, a state-mandated planning document. During the same period the City achieved 65% of housing for extremely-low and very-low households (those earning less than 50% of AMI).

But the City only produced 16% of the housing goal for low-income earners (50% to 79% of AMI), and 25% of housing needs for moderate-income earners (80% to 120% of AMI).

Looking at it by

income distribution, Table 3 in the Jury’s report notes that

high-income earners (over 120% of AMI) comprise 38% of all households

in San Francisco, and reached 113% of housing production, while

the extremely-low and very-low earners make up 30% of all households

and saw 65% of their housing construction goals, and while those

considered “middle income” (50% to 120% of AMI) make

up 32% of all San Francisco Households, but saw just 20% of their

housing construction needs met.

Looking at it by

income distribution, Table 3 in the Jury’s report notes that

high-income earners (over 120% of AMI) comprise 38% of all households

in San Francisco, and reached 113% of housing production, while

the extremely-low and very-low earners make up 30% of all households

and saw 65% of their housing construction goals, and while those

considered “middle income” (50% to 120% of AMI) make

up 32% of all San Francisco Households, but saw just 20% of their

housing construction needs met.

No wonder the Jury included findings that “housing development over the last decade has fallen far short of regional need targets,” and noted that “housing construction for middle-income households in not meeting regional housing targets,” either.

The Jury’s report noted the $1.3 billion Housing Trust Fund would receive $20 million in its initial first year in FY 13–14, with 70% ($13.8 million) of the $20 million budget allocated to “provide local financing for construction and major rehabilitation of affordable multifamily housing.” Nothing suggests that 70% of the HTF’s initial allocation was spent in the first year, as is discussed below in the section on MOHCD’s Annual Report released after the Grand Jury report.

Planning Department’s 2014 Housing Inventory Report

The Planning Department’s 2014 Housing Inventory Report reveals a host of data that is disturbing, at best.

In an introductory

highlight titled 2014 Snapshot, Planning reports there was a net

addition of 3,514 total units to the City’s housing stock

in (presumably) calendar year 2014, but only 757 of them —

just 21.5% — were new “affordable housing” units.

Clearly, the 21.5% figure is far short of the Mayor’s stated

policy goals and the Prop “K” declaration of policy

adopted by voters for 33% of affordable units for low-and moderate-income

households, let alone the goal of 50% to be affordable for middle-class

housing.

In an introductory

highlight titled 2014 Snapshot, Planning reports there was a net

addition of 3,514 total units to the City’s housing stock

in (presumably) calendar year 2014, but only 757 of them —

just 21.5% — were new “affordable housing” units.

Clearly, the 21.5% figure is far short of the Mayor’s stated

policy goals and the Prop “K” declaration of policy

adopted by voters for 33% of affordable units for low-and moderate-income

households, let alone the goal of 50% to be affordable for middle-class

housing.

Of the 757 new affordable units, Planning claims 267 (35%) were considered to be “on-site inclusionary” units, but the 267 inclusionary units represent just 7.6% of the total 3,514 net addition. The Inclusionary Affordable Housing Program that became effective in 2002 requires developers to either build affordable housing units on- or off-site of the principal development project, or pay an in-lieu inclusionary fee. Inclusionary units are rental units for households that earn up to 60% of Area Median Income (AMI), or first-time home buyer households with incomes between 70% and 110% of AMI.

For renters, 60% of AMI is $42,800 for a one-person household and up to $55,000 for a three-person household. For first-time buyers, 70% to 110% of AMI ranges from $49,950 to $78,500 for a one-person household and $64,200 to $100,850 for a three-person household.

And Planning says 83% of the 757 affordable units constructed in 2014 are rental units for very-low-income (20%) and low-income (63%) households. During the past five years, just 707 inclusionary units were developed since 2010, including the 267 constructed in 2014.

Just 17% — 131 units — of the 757 new affordable units in 2014 were for “moderate-income” households. “Moderate” is defined by the Planning Department as earning less than 120% of Area median Income (AMI). Not too surprisingly, Planning reports that rent for a two-bedroom home increased by nearly 40% in 2014 to $4,580 monthly in the greater Bay Area. Talk about middle-income housing withering on the housing production vine!

Planning notes that

fully 78.5% of the 3,514 new housing are market-rate housing and

just 21.5% are new affordable units. Just 33 single-family units

were added in 2014, representing only 1% of all new housing construction.

Fully 91% of new units were constructed in high-density buildings

with 20 or more units.

Planning notes that

fully 78.5% of the 3,514 new housing are market-rate housing and

just 21.5% are new affordable units. Just 33 single-family units

were added in 2014, representing only 1% of all new housing construction.

Fully 91% of new units were constructed in high-density buildings

with 20 or more units.

Planning reports that during the ten-year period dating back to 2005, there have also been 18,398 new condos constructed, including 1,977 in 2014. There were an additional 730 condo conversions in 2014, up fully 98% over the 369 condo conversions in 2013.

Planning notes that of the 3,514 new affordable units built in 2014, fully 96% were built in 10 eastern neighborhoods, including South of Market, Mission Bay, the Financial District/South Beach, Hayes Valley, Potrero Hill, Nob Hill, Castro/Upper Market Street, the Tenderloin, Bayview Hunters Point, and the Mission District. Just 4% — merely 145 new affordable units — were built throughout the rest of the City.

In Table A-1 showing major market-rate housing projects completed in 2014, Planning lists 17 projects by street address location totaling 3,358 market rate units built plus another 267 “affordable” units, for a total of 3,625 units, but didn’t specify whether the affordable units were built on- or off-site. The 267 affordable units represent just 7.4% of the 3,625 total units.

Of the 3,625 units, 614 (18.3%) are earmarked for ownership, 2,646 (78.8%) earmarked as rental units, and the remaining 98 units (2.9%) are a combination of ownership and rental units.

The market rate units built for ownership (rather than rental) range in initial sales price from $500,000 to $3.5 million, with the majority of them priced over $1 million. The market rate rental units range from $2,500 to $6,876 monthly for a studio unit, and $3,482 to a staggering $13,121 monthly for a two-bedroom unit. (The $13,121 is not a typo.) Fully 499 of two-bedroom units built will charge rent of over $6,880 monthly. Among the 27 projects, only 8 of 14 rental projects listed the planned number of two-bedroom units. A total 499 of two-bedroom rental units will be built, unless some of the other rental projects will also include two-bedroom units.

In Table A-2, Planning lists another 12 major affordable housing projects completed in 2014, totaling an additional 431 units, all of which are rental units for very low-income or low-income — and none for middle-income — households.

Finally, Planning reports that “In-Lieu” housing fees paid by developers totaled $116.8 million over the decade since 2005, including $29.9 million in partial payment of in-lieu fees in 2014 alone. Planning said it did not know how many units were not built, with developers opting to pay almost $117 million in In-Lieu fees across the past decade, instead; Planning said MOHCD shoul dkno who wmany units were not built.

Dryly, Planning notes housing policy implications may arise from data presented, which it didn’t address in its report. There are additional data in the Planning Department’s 2014 Housing Inventory report of interest — including housing production trends, housing demolition, and housing stock by Planning District — but is too detailed to cover here.

MOHCD’s Annual Report for 2012–2013 and 2013–2014

MOHCD’s belated Annual Report for FY 2012–2013 and 2013–2014 is riddled with nonsense. Of the five permitted uses for the Housing Trust Fund voters approved in 2012, MOHCD boasted that only four Downpayment Assistance Loan Program loans for first responders (police officers, sheriff’s deputies, and firefighters) were issued out of 10 planned loans for the first year in FY 13–14, and only four low-income homeowners had received assistance for remediation of lead issues. Other Housing Trust Fund components received anemic funding and anemic results, as well.

As I have previously reported, MOHCD’s Annual Report also acknowledges that Mayor Lee approved incurring bonded debt using the Housing Trust Fund as collateral. That’s like tapping into Grandma’s credit card from taxpayers to fund additional debt.

For openers, MOHCD’s Annual Report for the two fiscal years issued in early 2015 comically reported that key milestones for the Housing Trust Fund through June 2014 involved “The bulk of [the] FY 2013/2014 [$20 million General Fund investment] was spent defining and launching programs,” and that “$3,256,000 of the Housing Trust Fund was spent in its first year.” Basic math suggests that $16,744,000 — the bulk of its allocation — was not spent in its first year, by MOHCD’s own admission.

MOHCD apparently

didn’t stop to consider that $3.2 million in spending represented

just 16.3% of its first year allocation, leaving the bulk of 83.7%

unspent in its first year. This correlates to my reporting in

April 2014 that the City Controller had noted that almost nine

months into Fiscal Year 2013–2014, fully 92.8% of MOHCD’s

first year Housing Trust Fund allocation — $17.5 million

— had remained unencumbered (i.e., unspent).

MOHCD apparently

didn’t stop to consider that $3.2 million in spending represented

just 16.3% of its first year allocation, leaving the bulk of 83.7%

unspent in its first year. This correlates to my reporting in

April 2014 that the City Controller had noted that almost nine

months into Fiscal Year 2013–2014, fully 92.8% of MOHCD’s

first year Housing Trust Fund allocation — $17.5 million

— had remained unencumbered (i.e., unspent).

So which is it: The “bulk” was spent on defining and launching programs as MOHCD asserts, or the “bulk” was not spent at all, as MOHCD variously claims? Or is it that the Grand Jury was overly optimistic that 70% of the initial budget allocation would actually be spent financing actual housing projects?

The Annual Report notes the Housing Trust Fund will invest $15 million during its first five years for down-payment assistance loans at 0% interest over the life of the loans. But the report neglects to note that each loan is tied to a formula requiring repayment to the City a computed percentage of appreciation in the value of properties purchased to be repaid, along with the principal amount of the loan to the City, by subtracting the purchase price from the sales price, and applying a formula to the appreciated value based on the loan amount to the purchase price. The repaid loans have had to pay 12% to 30% of the net appreciation back to the City for the privilege of having been awarded a loan. This can hardly be considered interest free, 0% loans.

Indeed, MOHCD separately provided a list of 157 Downpayment Assistance Loan Program (DALP) loans issued between June 1998 and January 2013 and subsequently were repaid; the list shows that of $9,583,879 in DALP loans issued, on re-sale of the properties the City’s share of appreciation netted the City $4,572,156 in addition to the loan repayments. The City’s share of the appreciation represents 47.7% of the $9.58 million in loans MOHCD issued.

If this isn’t a classic definition of “usury” — the lending of money at exorbitant interest rates — I don’t know what else is. The City can claim all it wants that the loans are interest-free, but “sharing” such a large percentage of the appreciation with the City suggests otherwise. Is this Mayor Lee’s “sharing prosperity” agenda in action?

In contrast to the

Grand Jury’s policy concerns about affordable housing parity

and fair distribution of housing built for all income tiers, the

MOHCD Annual Report includes data about housing “entitled”

in the City’s housing development pipeline (i.e., projects

approved by the Planning Commission, but construction permits

have not yet been issued by the Department of Building Inspection).

In contrast to the

Grand Jury’s policy concerns about affordable housing parity

and fair distribution of housing built for all income tiers, the

MOHCD Annual Report includes data about housing “entitled”

in the City’s housing development pipeline (i.e., projects

approved by the Planning Commission, but construction permits

have not yet been issued by the Department of Building Inspection).

Although the Grand Jury noted the City had achieved 113% of market rate housing between 2007 and 2014 identified in the Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) goals, had achieved 65% of housing for extremely-low and very-low households (those earning less than 50% of AMI), and the City had only produced 16% of the housing goal for low-income earners and 25% of housing needs for moderate-income earners, MOHCD reported not only units constructed between 2007 and 2014, but also units approved and “entitled” in the housing pipeline.

As an MOHCD table below shows, when housing units “entitled” are added in, market rate units jump to 197% of all housing being developed, but just 26% were built and entitled for moderate income earners, and 62% of units have been built or entitled for low-income households. Wow! Almost 24,244 market-rate units (nearly 200%) constructed or “entitled,” or in development, but only 7,941 (26%) middle-income units? Does this sound like “parity” to you?

That “middle income” housing only reached 26% of units built or entitled during the 2014 Q2 pipeline, it’s clear that the goal of building 50% of new housing for the middle-class is falling far short of the Mayor’s stated policy goals and Supervisor Jane Kim’s declaration of policy “affordable” goals. More middle-class housing withering on the vines?

Additional data in

MOHCD’s Annual Report are of interest — including MOHCD’s

involvement in rebuilding public housing through the HOPE SF program,

HUD’s Rental Assistance Demonstration Program (RAD), and

housing revenue bonds — but is too detailed to cover in this

article.

Additional data in

MOHCD’s Annual Report are of interest — including MOHCD’s

involvement in rebuilding public housing through the HOPE SF program,

HUD’s Rental Assistance Demonstration Program (RAD), and

housing revenue bonds — but is too detailed to cover in this

article.

City Controller’s Biennial Development Impact Fee Report

The City Controller’s Biennial Development Impact Fee Report for FY 2012–2013 and 2013–2014 report lists a whole host of development impact fees charged to developers as a condition of approval for any given development project. The impact fees range from open space fees, bicycle parking in-lieu fees, to water capacity charges, school impact fees transit impact fees, child care fees, public art fees, street trees in-lieu fees, various neighborhood impact fees, along with both an Affordable Housing Job-Housing Linkage fee for commercial properties and residential Affordable Housing “Inclusionary” fees. Only the latter inclusionary fees are addressed in this article.

Of note, since FY 1988–1989, the City Controller reports that the City has collected affordable housing jobs-housing linkage fees of $73.995 million, and another $89.42 million in Affordable Housing Inclusionary Program fees, for a combined total of $176.68 million, including $13.26 million in interest earned. Across the two fees, $45.9 million remained unspent at the end of June 2014.

Both fees are deposited into the Citywide Affordable Housing Fund which is administered by MOHCD, and are used to provide assistance to low- and moderate-income homebuyers to finance eligible affordable housing projects, and to redevelop and rehabilitate affordable housing. Housing developers typically are awarded 55-year, low-interest loans.

Disturbingly, of

the $89.4 million in Affordable Housing Inclusionary Program Fees

collected since the program was introduced in FY 2005–2006,

$40.7 million remained unspent at the end of December 2014. Even

more disturbingly, there is no explanation offered as to why the

Planning Department reported that $116.8 million has been collected

in “in-lieu” inclusionary fees over the decade since

2005, but the City Controller is reporting the same program has

only collected $89.42 million. What’s with this unexplained

$27.4 million variance?

Disturbingly, of

the $89.4 million in Affordable Housing Inclusionary Program Fees

collected since the program was introduced in FY 2005–2006,

$40.7 million remained unspent at the end of December 2014. Even

more disturbingly, there is no explanation offered as to why the

Planning Department reported that $116.8 million has been collected

in “in-lieu” inclusionary fees over the decade since

2005, but the City Controller is reporting the same program has

only collected $89.42 million. What’s with this unexplained

$27.4 million variance?

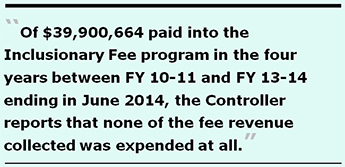

Neither the City Controller nor the Planning Department count fees returned to developers who do not move their projects forward. Oddly, of $39,900,664 paid into the Inclusionary Fee program in the four years between FY 10–11 and FY 13–14 ending in June 2014, the Controller reports that none of the fee revenue collected was expended at all. The Controller offered no explanation as to why none of the Inclusionary Fee fees collected were expended during the past four fiscal years.

Nearly $40 million collected during the past four years, and MOHCD can’t find anything to spend it on?

Troubling State of Housing

As

if the four reports discussed above aren’t troubling enough,

there are other concerns about the performance of the Mayor’s

Office of Housing, and the state of housing production in San

Francisco.

As

if the four reports discussed above aren’t troubling enough,

there are other concerns about the performance of the Mayor’s

Office of Housing, and the state of housing production in San

Francisco.

City Floats Housing Revenue Bonds

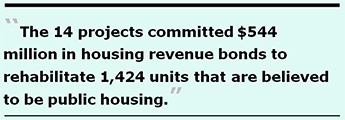

In addition to the $1.5 billion Housing Trust Fund, and the separate Affordable Housing Fund, MOHCD is involved in hundreds of millions of dollars in housing projects to rebuild the City’s public housing. On April 8, 2015 the Board of Supervisors Budget and Finance Sub-Committee meeting included 14 separate agenda items to rehabilitate residential rental housing projects throughout the City that will be funded by floating housing revenue bonds (that don’t require voter approval to issue). The 14 projects committed $544 million in housing revenue bonds to rehabilitate 1,424 units that are believed to be public housing.

The revenue bonds are thought to be repaid from rents paid by tenants over the life of a bond.

Two weeks later, on April 28 the full Board of Supervisors agenda included a multifamily housing revenue note for an additional $61.4 million to construct another 200 rental units at 588 Mission Bay Boulevard North. That brings the total to $605.4 million in just a one-month period for revenue bonds and revenue notes for a total of 1,624 units, only 200 of which are “new.”

It is not yet known

how many other housing revenue bonds and housing revenue notes

the City has approved in recent history, but the practice of issuing

revenue bonds and notes is expected to continue.

It is not yet known

how many other housing revenue bonds and housing revenue notes

the City has approved in recent history, but the practice of issuing

revenue bonds and notes is expected to continue.

MOHCD’s Failure to Respond to Records Requests

The Civil Grand Jury is not the first to have noted MOHCD’s

rotten record keeping. The Jury’s report noted:

On January 19, 2015,

I placed three separate records requests to 1) Obtain updated

information on the number of DLAP loans and loan amounts issued

to first responders for FY 13–14; 2) Obtain information concerning

the number of first-responder DALP loans issued to date in FY

14–15, and whether the planned loan amounts remain limited

to $100,000 loans, or whether they were increased to $200,000

loans; and 3) To obtain information on the new non-first responders

DLAP loan program implemented in FY 13–14, including the

number of non-first responder loans that were issued to date,

the number of applicants, the number of loans that remain under

consideration, and the amount of each non-first responder loan

issued.

On January 19, 2015,

I placed three separate records requests to 1) Obtain updated

information on the number of DLAP loans and loan amounts issued

to first responders for FY 13–14; 2) Obtain information concerning

the number of first-responder DALP loans issued to date in FY

14–15, and whether the planned loan amounts remain limited

to $100,000 loans, or whether they were increased to $200,000

loans; and 3) To obtain information on the new non-first responders

DLAP loan program implemented in FY 13–14, including the

number of non-first responder loans that were issued to date,

the number of applicants, the number of loans that remain under

consideration, and the amount of each non-first responder loan

issued.

On January 27 MOHCD’s point person, Eugene Flannery, finally got around to responding. Notably, Flannery provided just one Excel file listing loan applications received dating as far back as December 2011, data that I had not requested. There is no way to filter the codes in Excel for the type of loans to isolate the non-first responder loans that began in FY 14–15, and no way to judge how many applicants had applied for the non-first responder loans under the Housing Trust Fund.

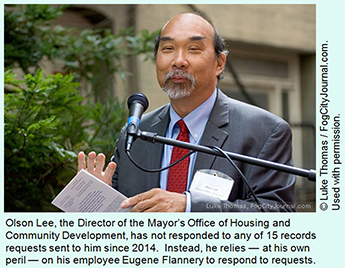

This reporter has filed 15 e-mail requests for public records to Olson Lee since March 18, 2014, and have received eight “read” receipts in 2015 that he ostensibly opened and read the records requests. He has not responded to any of the 15 e-mails, relying at his own peril on Eugene Flannery to respond, instead. Surely Mr. Lee knows that the Ethics Commission ruled on August 8, 2014 that John Rahaim, Director of the Planning Department had violated Section 67.21(a) of San Francisco’s Sunshine Ordinance because Rahaim’s employees had failed to provide records without unreasonable delay, and by virtue of Rahaim’s supervisorial role over department staff, he was responsible for the Planning Department’s bungled response for public records. Why should this be any different for Mr. Olson Lee?

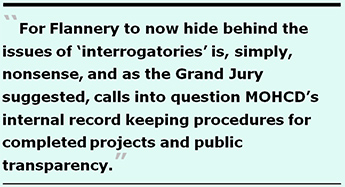

Flannery pointedly advised me that a request that a Department

create records to respond to a request for information or answer

a series of questions is not a public records request, and neither

the Public Records Act nor the Sunshine Ordinance requires a Department

to reply to a series of written “interrogatories.” The

data I requested in the three separate records requests were not

“interrogatory” questions, but requests for very specific

data sets and documents.

A year earlier, Flannery had, however, reluctantly provided data

regarding the first-responder DALP loans for FY 13–14 in

March and April of 2014.

For Flannery to now

hide behind the issues of “interrogatories” is, simply,

nonsense, and as the Grand Jury suggested, calls into question

MOHCD’s internal record keeping procedures for completed

projects and public transparency. Two formal Sunshine Ordinance

Task Force complaints have been filed over MOHCD’s failure

to provide meaningful public records.

For Flannery to now

hide behind the issues of “interrogatories” is, simply,

nonsense, and as the Grand Jury suggested, calls into question

MOHCD’s internal record keeping procedures for completed

projects and public transparency. Two formal Sunshine Ordinance

Task Force complaints have been filed over MOHCD’s failure

to provide meaningful public records.

Flannery’s reliance on “interrogatories” is ridiculous, since many other City departments, including the City Controller’s Office, routinely respond to follow-up questions raised about information in public records. Why can’t MOHCD do the same?

Where’s the $70 Million in “Inclusionary Housing Fees” Paid?

The Mayor must be hoping that when voters cast their ballots in November 2015 on his proposed $250 million housing bond, voters won’t remember that $170 million has been assessed against housing developers for in-lieu Inclusionary Housing projects that developers opted to pay in fees, rather than construct.

A separate records request to Chandra Egan in the Mayor’s Office of Housing on May 3, 2015 unearthed a list of Inclusionary Housing Program Projects dating back to December 2002. The list shows that of 54 projects since 2002, developers were assessed inclusionary housing program fees on a total of 3,949 units subject to Planning Code Section 415 governing on- and off-site housing vs. the in-lieu fees.

It appears developers

chose to pay $170.5 million in in-lieu fees, rather than building

485 units on the principal project sites. The in-lieu fees paid

to date (as of February 12, 2015) totals $113.5 million, with

$57 million outstanding due to fee deferrals. Provided that none

of the planned units are scrapped, the deferred fees will ostensibly

be paid eventually.

It appears developers

chose to pay $170.5 million in in-lieu fees, rather than building

485 units on the principal project sites. The in-lieu fees paid

to date (as of February 12, 2015) totals $113.5 million, with

$57 million outstanding due to fee deferrals. Provided that none

of the planned units are scrapped, the deferred fees will ostensibly

be paid eventually.

But this begs several questions: What has MOHCD done with the $113.5 million in inclusionary fees it has collected to date, and what are its plans for the outstanding $57 million in deferred fees? It needs to show us the money!

And MOHCD needs to explain whether the $170 million includes the Affordable Housing Job-Housing Linkage fees, in order to reconcile data provided by the Controller’s Office.

MOHCD’s Second-Year Budget Performance

A separate records request to the City Controller unearthed MOHCD’s second-year HTF budget “actuals.” Although the budget was expected to total $22.8 million in funding, surprisingly, the second-year budget soared to $39.1 million by rolling over almost $16 million — $12,947,101 in an unencumbered balance, plus $3,381,512 in encumbered funds that were never spent — from its prior year budget in FY 13–14.

How does MOHCD get away with failing to spend the HTF in the years appropriated, for two years in a row? Surely they must have heard San Francisco has a housing crisis, so what kind of stewardship is this?

A quick analysis of the revised budget reveals several troubling

issues showing that the planned uses of the Housing Trust Fund

sold to voters in 2012 are not being met. As of this writing,

nine months into the current FY 2014–2015, (July 1, 2014

through March 2015) a cross-tab analysis of the second year HTF budget “actuals”

shows:

Of $1,882,060 budgeted

for the HTF’s “Small Site Acquisition” component

— a program to acquire and rehabilitate multi-family rental

buildings of 5 to 25 units — no expenditures have been made

to date, and the $1.9 million remains totally unencumbered (unspent

and unobligated).

Of $1,882,060 budgeted

for the HTF’s “Small Site Acquisition” component

— a program to acquire and rehabilitate multi-family rental

buildings of 5 to 25 units — no expenditures have been made

to date, and the $1.9 million remains totally unencumbered (unspent

and unobligated). Although a non-first

responders DALP program was to be set up, the original second-year

budget for DALP loans for non-first-responders was reduced from

$2 million to just $13,514 (as in thirteen-thousand). In its

place, the budget printout shows that 20 downpayment loans were

issued in separate line items, five of which were for $200,000

loans, four were for $140,000 loans, and 11 of which were loans

of $57,000 and below. The latter loans may be for “Below

Market Rate” loans, a different housing program from the

“affordable” Housing Trust Fund voters were promised.

Although a non-first

responders DALP program was to be set up, the original second-year

budget for DALP loans for non-first-responders was reduced from

$2 million to just $13,514 (as in thirteen-thousand). In its

place, the budget printout shows that 20 downpayment loans were

issued in separate line items, five of which were for $200,000

loans, four were for $140,000 loans, and 11 of which were loans

of $57,000 and below. The latter loans may be for “Below

Market Rate” loans, a different housing program from the

“affordable” Housing Trust Fund voters were promised.The Mayor is so hell-bent on rebuilding public housing as quickly as he can that he’s diverting affordable housing funds for the middle-class, to fund public housing improvements. Therein lies the danger of handing MOHCD sole discretion on how the $1.5 billion Housing Trust Fund will be spent over the next 30 years.

This is the same Mayor who wants voters to approve his $250 million housing bond next November and to re-elect him. Given the Mayor’s track record, why would voters do either?

The Board of Supervisors needs to quickly schedule a hearing on MOHCD’s performance with the Housing Trust Fund in 2015 and not wait until the fifth year to do so in 2018. And the Supervisors need to create some sort of Board or Commission having oversight over all of MOHCD, which currently does not have one. After all, the displacement of thousands of San Franciscans and the state of San Francisco’s housing crisis suggests the Supervisors need to move quickly to improve MOHCD’s transparency.

Monette-Shaw is an open-government accountability advocate, a patient advocate, and a member of California’s First Amendment Coalition. He received the Society of Professional Journalists-Northern California Chapter’s James Madison Freedom of Information Award in the Advocacy category in March 2012. Feedback: monette-shaw@westsideobserver.

Postscript

Postscript

After this article was submitted to the Westside Observer for print publication, additional information surfaced that is also troubling.

First, an MOHCD PowerPoint presentation prepared in 2013, after voters approved the Housing Trust Fund in November 2012, was located on MOHCD’s web site. The PowerPoint presentation was apparently created by MOHCD for a presentation to the San Francisco Family Support Network (SFFSN). SFFSN bills itself as a “unique partnership of stakeholders in the Family Support field.”

One slide in the presentation describes the Affordable Housing Pipeline, including “target populations” that includes the “homeless, transition-age youth, seniors, families, the disabled, moderate income homeownership, and public housing replacement.”

Disturbingly, another slide asserts that the Housing Trust Fund will play a critical role in funding “completion of 3,000 units for the chronically homeless,” ostensibly as part of the City’s 10-Year Plan to End Chronic Homelessness, and completion of 400 units for homeless Transition Age Youth.

Just as voters were not told before November 2012 that the Housing Trust Fund would be raided to provide funding to the Housing Authority successor agency, voters were also not told that the Housing Trust Fund would be tapped to develop supportive housing, complete with services, for the homeless.

Second, a “Draft 2015–2016 Action Plan” submitted to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Community Planning and Development was also located on MOHCD’s web site. The Action Plan includes preliminary funding allocations, including from San Francisco’s General Fund that will presumably be awarded, contingent on Board of Supervisors’ approval of the Mayor’s proposed budget for FY 15–16 starting July 1, 2015.

The Action Plan clearly states the Housing Trust Fund will have a $50.6 million allocation for the HTF’s third year budget “of which $25 million is borrowed and will be repaid from future HTF allocations.” There you have it, not only did Mayor Lee decide in 2014 to permit incurring bonded debt using the Housing Trust Fund as collateral, it appears he has also approved borrowing against future General Fund allocations to the HTF to scale up the HTF annual budgets.

Voters were told

in 2012 that $2.8 million would be added each year to the HTF’s

previous year budget, and that it would take fully 12 years until

the General Fund would begin providing $50.8 million annually

to the HTF. In an effort to quickly scale up to $50 million annually,

the Mayor is borrowing against future year General Fund allocations

to rapidly get to the $50 million annual threshold.

Voters were told

in 2012 that $2.8 million would be added each year to the HTF’s

previous year budget, and that it would take fully 12 years until

the General Fund would begin providing $50.8 million annually

to the HTF. In an effort to quickly scale up to $50 million annually,

the Mayor is borrowing against future year General Fund allocations

to rapidly get to the $50 million annual threshold.

The HTF’s third-year budget should have been just $25.6 million, but will reach $50.6 million in its third funding cycle by “creative” borrowing against future HTF allocations.

The Action Plan also appears to report that a new line item for MOHCD’s HOME program may be included in the HTF annual budget for FY 15–16 totaling $6.12 million for the HOME Housing Development Pool.

According to HUD’s web site, HUD’s HOME Investment Partnerships Program (HOME) provides formula grants to States and localities that communities use — often in partnership with local nonprofit groups — to fund a wide range of activities including building, buying, and/or rehabilitating affordable housing for rent or homeownership or providing direct rental assistance to low-income people. HOME is the largest Federal block grant to state and local governments designed exclusively to create affordable housing for low-income households.

The Action Plan notes that $1,875,343 of the $6.12 million HOME allocation will come from HOME program income (presumably a HUD block grant). It is not yet known whether the balance of the $6.12 million HOME allocation — $4,244,293 — will come from the City’s General Fund or other sources of funding, or whether the HTF will be tapped to flesh out the $1.88 million HOME program income.

Sadly, the Action Plan makes no mention of how many units of housing may (or may not) be developed using the $6.12 million HOME Housing Development Pool.

The Action Plan also includes additional funding recommendations to use an additional $1,605,000 from the Housing Trust Fund in FY 15–16 for three goals for Objective 1, “Families and Individuals Are Stably Housed,” and one goal for Objective 2, “Communities Have Healthy Physical, Social and Business Infrastructures.”

Of this $1.6 million pot of HTF funding recommendation:

Goal 1Ci, “Reduced

Rate of Evictions” in Priority Need 1C “Prevent

and Treat Homelessness,” allocates $955,000 (60% of

the $1.6 million) to eight nonprofit organizations, principally

to provide tenant counseling, homeless prevention counseling,

housing counseling, and eviction prevention to residents of public

housing being converted to Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD)

projects to help residents avoid eviction, for an unknown number

of tenants.

Goal 1Ci, “Reduced

Rate of Evictions” in Priority Need 1C “Prevent

and Treat Homelessness,” allocates $955,000 (60% of

the $1.6 million) to eight nonprofit organizations, principally

to provide tenant counseling, homeless prevention counseling,

housing counseling, and eviction prevention to residents of public

housing being converted to Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD)

projects to help residents avoid eviction, for an unknown number

of tenants.It’s clear that voters in 2012 were not told the Housing Trust Fund would subsidize providing “supportive services” to homeless people along with developing 3,000 units for the chronically homeless, in addition to never having been told that the Housing Trust Fund would divert affordable housing funds for the middle-class to fund public housing improvements, instead.

Given the Mayor’s performance with the Housing Trust Fund in its first two years — all at the sole discretion of MOHCD — and given a glimpse of preliminary planned funding allocations for the Housing Trust Fund’s third year, it’s clear voters were snookered into believing the Housing Trust Fund would actually develop affordable housing, including for middle-income households.

It’s painfully clear that middle-class housing production in San Francisco is rapidly withering on the vine.