Article

in Press Printer-friendly PDF file

Article

in Press Printer-friendly PDF fileWestside Observer

March 2015 at www.WestsideObserver.com

Part 2: Gambling With San Francisco Employees’ Retirement Fund

Wendy Paskin Jordan’s Troubling Reappointment

Article

in Press Printer-friendly PDF file

Article

in Press Printer-friendly PDF file

Westside Observer

March 2015 at www.WestsideObserver.com

Part

2: Gambling With San Francisco Employees’ Retirement Fund

Wendy Paskin

Jordan’s Troubling Reappointment

by Patrick Monette-Shaw

In his haste to reappoint Wendy Paskin-Jordan — wife of former Mayor and former Police Chief Frank Jordan — to the San Francisco Employees’ Retirement System’s (SFERS) Board of Directors, Mayor Ed “Shared Prosperity Agenda” Lee sloppily ignored vetting his reappointment recommendation required through the San Francisco Board of Supervisors Rules Committee where public testimony and a Rules Committee recommendation to approve or oppose mayoral appointees are then forwarded to the full Board of Supervisors for consideration.

Paskin-Jordan has a number of conflicts of interest that should have disqualified her from reappointment. Mayor Lee just turned a blind eye. Later, San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors turned a blind eye, too.

As widely-respected

financial journalist David Sirota noted in an International

Business Times article on December 13, 2014, Paskin-Jordan

“appears to have blurred the lines between her responsibility

to the city and her personal financial interests.” Sirota

reported “Paskin-Jordan has invested her personal funds in

a firm called GMO, which also manages almost $400 million of the

San Francisco pension system’s money.”

As widely-respected

financial journalist David Sirota noted in an International

Business Times article on December 13, 2014, Paskin-Jordan

“appears to have blurred the lines between her responsibility

to the city and her personal financial interests.” Sirota

reported “Paskin-Jordan has invested her personal funds in

a firm called GMO, which also manages almost $400 million of the

San Francisco pension system’s money.”

Sirota reported that “San Francisco has rules designed to prevent people who manage pension systems from placing personal money in the same entities in which public funds under their supervision are invested.” In addition to concerns about her relationship with GMO, it’s unclear whether Paskin-Jordan and her clients have also invested in Northern Trust by aggregating personal funds with SFERS’ pension funds, a key question all but ignored by San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors when it held a second hearing on her reappointment on January 7, 2015. She had been a no-show at the Board of Supervisors first hearing on December 16, 2014.

When the Mayor failed to follow the required process, instead of starting the reappointment process over with a referral to the Rules Committee, the Board succumbed to political pressure and scheduled a December 2014 hearing of the Board sitting as a Committee of the Whole to consider the Mayor’s reappointment of Paskin-Jordan’s. Paskin-Jordan tweaked the Board’s collective noses when she failed to appear to appear at the Board’s December 16 hearing, forcing the Board to schedule a special meeting that was held on January 7, 2015, the last date possible to consider the reappointment within the maximum 30-day period allowed.

Paskin-Jordan’s

investment firm — Paskin Capital Advisors, LLC — has

$627 million in assets under management for her clients. Her

activities have raised serious concerns about her fitness to be

an SFERS Commissioner.

Paskin-Jordan’s

investment firm — Paskin Capital Advisors, LLC — has

$627 million in assets under management for her clients. Her

activities have raised serious concerns about her fitness to be

an SFERS Commissioner.

Two Conflict-of-Interest Ethics Complaints

When Mayor Lee recommended handing Paskin-Jordan a five-year reappointment to SFERS Board, he had to have known that two conflict-of-interest complaints against Paskin-Jordan had already been filed with the City’s Ethics Commission.

Luckily, the Board of Supervisors were aware of the two separate formal anonymous complaints about Paskin-Jordan’s Form 700’s Statement of Economic Interests (SEI) that had been filed with the Ethics Commission in 2014.

The first Ethics complaint filed on April 3, 2014 to SFERS, with copies to the Ethics Commission, alleged Paskin-Jordan had potentially received reduced fee structures for her account and her client’s accounts by aggregating SFERS’ fund balance with that of her and her clients accounts, saving her millions of dollars in investment and transaction fees. The complaint also claims she had received favorable fee structures for her business, and her clients doing business, with Northern Trust between September 2011 and September 2013.

Finally, the first

Ethics complaint alleged that she and her clients are receiving

special favors as a result of her appointment to SFERS, and SFERS’

relationships and investments with 43 named financial firms, including

GMO’s Quality Fund (that she invested in personally), BGI,

Bank of America, and Northern Trust, all of which SFERS has, does,

or may do business with.

Finally, the first

Ethics complaint alleged that she and her clients are receiving

special favors as a result of her appointment to SFERS, and SFERS’

relationships and investments with 43 named financial firms, including

GMO’s Quality Fund (that she invested in personally), BGI,

Bank of America, and Northern Trust, all of which SFERS has, does,

or may do business with.

The second ethics complaint alleging Paskin-Jordan’s financial misconduct dated September 2, 2014 involves a violation of the Statement of Incompatible Activities applicable to SFERS Board members, regarding Paskin-Jordan’s investments in GMO’s Quality Fund. SFERS Executive Director Jay Huish forwarded the second complaint to San Francisco Ethics Commission Executive Director, John St. Croix on December 8, the same date the Mayor reappointed her to SFERS.

As John Coté reported in the San Francisco Chronicle on December 15, 2014, the September complaint “centers on her investment of between $100,001 and $1 million in Grantham, Mayo, Van Otterloo and Co., an international investment firm headquartered in Boston known as GMO that has a minimum investment threshold of $10 million.”

Coté noted that City law prohibits Retirement Board members from investing with “managers of private equity, limited partnerships and non-publicly traded mutual funds that are doing business” with the City’s retirement system. GMO describes itself on its website as “a private partnership,” although San Francisco Employees’ Retirement System staff considers GMO a “manager of public market assets,” despite the $10 million minimum investment threshold.

Not only does GMO consider itself a “private partnership,” and not a “public market,” GMO notes on its web site that:

GMO also notes on its web site that:

As Supervisor John

Avalos noted during the Board of Supervisors hearing on December

16 on Paskin-Jordan’s reappointment, GMO is not listed on

eBay as an investment opportunity open to run-of-the-mill public

investors. The GMO fund does not appear to be a “publicly

traded mutual fund,” but when the Supervisors finally grilled

Paskin-Jordan on January 7, the question of whether GMO was indeed

a publicly-traded investment Paskin-Jordan was entitled to invest

in, the question didn’t garner sufficient scrutiny by the

10 City supervisors. Paskin-Jordan claimed several times on January

7 that GMO was a “public mutual fund,” despite the fact

GMO itself notes it’s a private fund that trades in hedge

funds, not exclusively in mutual funds.

As Supervisor John

Avalos noted during the Board of Supervisors hearing on December

16 on Paskin-Jordan’s reappointment, GMO is not listed on

eBay as an investment opportunity open to run-of-the-mill public

investors. The GMO fund does not appear to be a “publicly

traded mutual fund,” but when the Supervisors finally grilled

Paskin-Jordan on January 7, the question of whether GMO was indeed

a publicly-traded investment Paskin-Jordan was entitled to invest

in, the question didn’t garner sufficient scrutiny by the

10 City supervisors. Paskin-Jordan claimed several times on January

7 that GMO was a “public mutual fund,” despite the fact

GMO itself notes it’s a private fund that trades in hedge

funds, not exclusively in mutual funds.

Can anyone who is reading this invest in this fund without the $10 million minimum threshold? Aren’t you — as members of “the public” — entitled to invest in this “publicly-traded” mutual fund, as Paskin-Jordan is? How did she become more “entitled” than you or I?

Observers believe Ms. Paskin-Jordan’s affiliations with, and investments in, GMO’s Quality Fund represents, at minimum a perceived conflict of interest. Sirota reported December 13 that a letter from SFERS’ executive director Jay Huish to the Ethics Commission defended her, claiming Paskin-Jordan was given the right to invest in the GMO fund at a lower level [of investing] before she was appointed to SFERS’ board, and that it was, therefore, permissible. Paskin-Jordan didn’t personally invest in GMO until August 30, 2011 after she had already been on the pension board for over a year.

Indeed, she failed

to report her investment in the GMO Quality Fund — an equity

fund investment — on her Form 700 for the period ending December

31, 2011 in April 2012, and only got around to reporting in March

2013 that investment on her Form 2012 for the period ending December

31, 2012, fully 16 to 19 months after acquiring it in August 2011.

This bears repeating: She only finally disclosed the GMO investment

in March 2013. Why hadn’t she disclosed her “opportunity”

earlier, only disclosing the investment while sitting as an SFERS

Commissioner 16 months after she finally exercised the “opportunity”?

Indeed, she failed

to report her investment in the GMO Quality Fund — an equity

fund investment — on her Form 700 for the period ending December

31, 2011 in April 2012, and only got around to reporting in March

2013 that investment on her Form 2012 for the period ending December

31, 2012, fully 16 to 19 months after acquiring it in August 2011.

This bears repeating: She only finally disclosed the GMO investment

in March 2013. Why hadn’t she disclosed her “opportunity”

earlier, only disclosing the investment while sitting as an SFERS

Commissioner 16 months after she finally exercised the “opportunity”?

The Board of Supervisors and Deputy City Attorney Jon Givner who advises the Board of Supervisors, appear to have perhaps failed to review all SFERS contracts that came before the SFERS Board between the time that Paskin-Jordan acquired the GMO investment in August 2011 and when she finally disclosed the investment in March 2013.

Gaming the System?

In addition to Paskin-Jordan’s questionable conflicts-of-interest, other observers also question whether she feels entitled to game the system.

First, Mayor Lee noted in a short biography of Paskin-Jordan attached to his reappointment letter, that she served on Barclays Global Investors’ board of directors until it was acquired by BlackRock. The Mayor claims she serves as a Trustee of various funds of BlackRock Funds. She probably should have rescued herself — but didn’t — from a key SFERS vote involving BlackRock Investments during a full SFERS Board meeting on May 8, 2013, when the Board entertained a motion to terminate BlackRock Investments from a currency overlay program that did involve hedge funds. Although she cast a vote to terminate BlackRock, she shouldn’t have voted at all, given her probable conflict of interest.

Bloomberg Businessweek reports in Paskin-Jordan’s bio not only that she served as a Trustee of various funds of BlackRock Funds, including its Master Investment Portfolios, it also reports that she serves as a Trustee of BGI’s Audit Committee and Member of its Nominating and Governance Committee; and as a Trustee of BGI’s Prime Money Market Fund, BGI’s Government Money Market Fund - Institutional Shares, and BGI’s Treasury Money Market Fund - Institutional Shares.

Given SFERS’

involvement with BGI, her affiliations as a Trustee of various

BGI money market funds should have been thoroughly investigated

— which the Board of Supervisors completely failed to do

— in part because BGI was one of SFERS’ currency overlay

managers that contributed to the $60+ million in SFERS losses

over eight years. Meeting minutes of SFERS Board meetings do

not reveal she ever rescued herself during discussions involving

investing in BGI.

Given SFERS’

involvement with BGI, her affiliations as a Trustee of various

BGI money market funds should have been thoroughly investigated

— which the Board of Supervisors completely failed to do

— in part because BGI was one of SFERS’ currency overlay

managers that contributed to the $60+ million in SFERS losses

over eight years. Meeting minutes of SFERS Board meetings do

not reveal she ever rescued herself during discussions involving

investing in BGI.

Pensions & Investments columnist Randy Diamond reported on December 17, 2014 that Huish said Paskin-Jordan had received a “threshold waiver” to invest with GMO [to get around the $10 million minimum investment threshold]. SFERS has repeatedly claimed that she had received this “waiver” before becoming an SFERS Commissioner, trying to justify why she had waited until a year after being appointed to the SFERS Board before finally exercising her “waiver.” Diamond also reported that Huish claims SFERS “considers GMO a manager of public market assets,” ignoring GMO’s own claim that it offers private investments, not public investments.

Directly after the Board of Supervisors hearing on January 7, 2015, Paskin-Jordan was interviewed by the Labor Video Project and a YouTube video of the interview was posted on-line. In it, Huish asserts that Deputy City Attorney Jon Givner (who advises the Board of Supervisors during its meetings) had ruled that she had been “off [of BGI’s] Board long enough that she didn’t have to recuse herself.” The City Attorney didn’t state when she left BGI’s board, and what date she had voted on any SFERS investments with BGI in order to gauge how much time had elapsed. But the truth is, she continues to serve as a Trustee of BGI, if not as a BGI Board member, which the City Attorney’s Office had to have known about. Are we expected to believe that Trustees are somehow exempt from recusal requirements that apply to Board members who are not exempt from recusal?

Who’s Aggregating Whom?

Oddly, during the

Labor Video interview on January 7, Paskin-Jordan belatedly claimed

that her firm (Paskin Capital Advisors) had reached the $10 million

threshold by aggregating funds. She didn’t reveal any details

about who she or her clients had aggregated investments with to

apparently reach BGI’s $10 million threshold. It’s

an odd claim, as it had gone unreported by other media outlets

prior to January 7, including Pensions & Investments,

Bloomberg Businessweek, the San Francisco Chronicle,

and the International Business Times, among other media

outlets.

Oddly, during the

Labor Video interview on January 7, Paskin-Jordan belatedly claimed

that her firm (Paskin Capital Advisors) had reached the $10 million

threshold by aggregating funds. She didn’t reveal any details

about who she or her clients had aggregated investments with to

apparently reach BGI’s $10 million threshold. It’s

an odd claim, as it had gone unreported by other media outlets

prior to January 7, including Pensions & Investments,

Bloomberg Businessweek, the San Francisco Chronicle,

and the International Business Times, among other media

outlets.

The Board of Supervisors failed on January 7 to dig deeply enough into the question of who Paskin-Jordan — by her own admission to the Labor Video Project — had aggregated funds with, and when. Hopefully the Ethics Commission will not ignore her admission that she had aggregated funds as the Ethics complaint against her had alleged.

Another question involving gaming the system involves her ownership

of a condominium at 990 Union Street: In a June 21, 1995 article

by Larry Bush that appeared in the San Francisco Weekly

titled “Jordan vs. Jordan: Candidate Promises, Citizen

Mayor Delivers?,” Bush reported that in 1991, while earning

a Wells Fargo income of more than $100,000 a year, Paskin claimed

the right to purchase a condominium at 990 Union that had been

reserved by the Planning Commission for moderate-income buyers.

The two-bedroom condo was priced at $109,000, while similar units

in the building then carried a market price of up to $300,000.

Bush reported that Paskin had sued to win ownership of the unit

and settled the case on Election Day 1991.

A check of the Assessor-Recorder’s

web site on January 4, 2015 shows that the deed to that property

was transferred to a Revocable Trust in the names of Frank and

Wendy Paskin-Jordan on June 3, 2002. Bush reported in 1995 that

the Paskin-Jordan’s rent the unit at market rate, not at

affordable-rents rate, thus adding to “a scarcity of housing

that is within reach” of San Franciscans being frozen out

of the housing market. Paskin-Jordan’s most current Form

700, Statement of Economic Interests, for the period ending

December 31, 2013 reports that she earns between $10,001 and $100,000

in rent on the 990 Union property, but the names of each of her

tenants from whom she earned more than $10,000 in rent were redacted.

Her Form 700 indicates the “Fair market value” of 990

Union is between $100,000 and $1,000,000.

A check of the Assessor-Recorder’s

web site on January 4, 2015 shows that the deed to that property

was transferred to a Revocable Trust in the names of Frank and

Wendy Paskin-Jordan on June 3, 2002. Bush reported in 1995 that

the Paskin-Jordan’s rent the unit at market rate, not at

affordable-rents rate, thus adding to “a scarcity of housing

that is within reach” of San Franciscans being frozen out

of the housing market. Paskin-Jordan’s most current Form

700, Statement of Economic Interests, for the period ending

December 31, 2013 reports that she earns between $10,001 and $100,000

in rent on the 990 Union property, but the names of each of her

tenants from whom she earned more than $10,000 in rent were redacted.

Her Form 700 indicates the “Fair market value” of 990

Union is between $100,000 and $1,000,000.

The real estate web site, Zillow, estimates 990 Union is worth

$884,768, but Zillow also estimates that 990 Union may have an

upward range of $1.01 million. As hot as San Francisco’s

real estate market currently is, Zillow’s $1.01 million estimate

appears to be more likely, because an analysis by the Paragon

Real Estate Group shows that the median price for two-bedroom

condos (ostensibly at fair market value) in Paskin-Jordan’s

Russian Hill neighborhood stood at $1.325 million as of June 2014.

It’s hard to believe that a property Paskin-Jordan acquired

for $109,000 has not in the intervening 25-year period increased

in fair market value to over $1,000,000 — which is now on

the low end of current market-rate two-bedroom condos. Observers

question whether she may be potentially under-reporting the fair

market value of her 990 Union property on her Form 700’s

by reporting her $109,000 purchase price in 1991, not the current

fair market value of that property.

Board

of Supervisors Rubber-Stamps Paskin-Jordan’s Reappointment

Board

of Supervisors Rubber-Stamps Paskin-Jordan’s Reappointment

Although Coté quoted Supervisor Avalos on December 15 that the Board of Supervisors had “failed to scrutinize [Mel] Murphy’s reappointment [to the Port Commission] closely enough, we shouldn’t be doing that with Wendy Paskin-Jordan.” But when push came to shove, the Board of Supervisors also failed to scrutinize Paskin-Jordan closely enough, all but giving her a free pass on several probable conflicts of interest.

Despite all of the ethical concerns raised regarding her reappointment, the Board of Supervisors unanimously approved reappointment of Paskin-Jordan on January 7. They did so without probing into any of these questions, other than discussion of whether she needs to recuse herself in the future from voting on any of SFERS’ banking-related issues involving Northern Trust.

The Board of Supervisors should have stopped her reappointment dead in its tracks. Instead, they handed her a get-out-of-jail-free card.

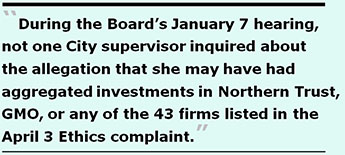

Unfortunately, during the Board’s January 7 hearing, not one City supervisor inquired about the allegation that she may have had aggregated investments in Northern Trust, GMO, or any of the 43 firms listed in the April 3 Ethics complaint.

The allegation of aggregating investments involves whether clients at Paskin-Jordan’s investment firm would benefit. That is, was any portion of SFERS $20 billion pension fund balance added to her own millions in fund balances so she or her clients could receive the same rate as SFERS, in effect receiving a volume discount on fees?

The April 3, 2014 Ethics complaint clearly asserted she had received favorable fee structures, possibly with Northern Trust. Northern Trust is SFERS’ custodial bank. While Paskin-Jordan admitted to the Labor Video Project that she had aggregated funds to qualify for investing in GMO, she has not yet indicated whether she also aggregated funds with Northern Trust.

[Editor: She has not acknowledged that, perhaps because the two Ethics Commission complaints against her are still on-going. It’s clear that the Ethics Commission should take note of Paskin-Jordan’s own admission to the Labor Video Project that she had been involved in aggregating funds to qualify for the GMO threshold, an accusation alluded to in the April 3 ethics complaint.]

When Supervisor Avalos

asked Paskin-Jordan on January 7 whether she had a “relationship”

with Northern Trust, she replied, “I do have a relationship

with Northern Trust. I work in [Northern Trust’s] Trust

Department,” explaining that is very different than SFERS’

work with Northern Trust’s custodial banking or securities

areas. She appears to have used poor phrasing, since observers

think she doesn’t actually work at Northern Trust,

she simply works with Northern Trust.

When Supervisor Avalos

asked Paskin-Jordan on January 7 whether she had a “relationship”

with Northern Trust, she replied, “I do have a relationship

with Northern Trust. I work in [Northern Trust’s] Trust

Department,” explaining that is very different than SFERS’

work with Northern Trust’s custodial banking or securities

areas. She appears to have used poor phrasing, since observers

think she doesn’t actually work at Northern Trust,

she simply works with Northern Trust.

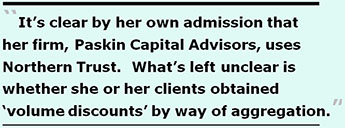

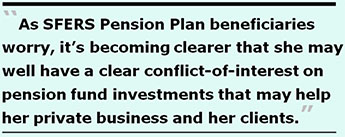

It’s clear by her own admission that her firm, Paskin Capital Advisors, uses Northern Trust. What’s left unclear is whether she or her clients obtained “volume discounts” by way of aggregation. And as SFERS Pension Plan beneficiaries worry, it’s becoming clearer that she may well have a clear conflict-of-interest on pension fund investments that may help her private business and her clients. How will, or how has, this affected her vote on the hiring of a new custodial bank for SFERS, which was recently underway?

Towards the end of the Board’s hearing, Deputy City Attorney Givner indicated the City Attorney’s office will work closely with SFERS to make sure she recuses herself from voting on contracts before SFERS involving Northern Trust. Oddly, Givner didn’t specify whether Paskin-Jordan would be monitored involving all recusals from matters involving BGI or other external investment managers.

Indeed, in response to yet another records request placed by this author for this article, SFERS acknowledged that “Commissioner Paskin-Jordan recused herself at the Board meeting of April 10, 2013 from participation in the agenda item ’Consideration of level I and Level II Engagement of Certain Bank Mortgage Servicing Companies under SFERS Social Investment Policies and Procedures’.” That’s it: A single recusal since having been appointed to SFERS in 2010. SFERS also responded that she had no other recusals at either the full Board level, or at subcommittee meetings.

Free Pass of Fossil Fuels Divestment

Critics of Paskin-Jordan

accuse of her of delaying for almost two years SFERS’ divestment

in fossil fuel investments, given that the Board of Supervisors

passed a resolution in 2013 recommending that SFERS divest from

fossil fuels. The majority of the Board’s cross-examination

of Paskin-Jordan on January 7 focused on the fossil fuels divestment

rather than other weighty issues detailed in the two ethics complaints

against her.

Critics of Paskin-Jordan

accuse of her of delaying for almost two years SFERS’ divestment

in fossil fuel investments, given that the Board of Supervisors

passed a resolution in 2013 recommending that SFERS divest from

fossil fuels. The majority of the Board’s cross-examination

of Paskin-Jordan on January 7 focused on the fossil fuels divestment

rather than other weighty issues detailed in the two ethics complaints

against her.

Avalos focused heavily on whether she had been present at several SFERS Board meetings, including one on February 19, 2014. She fought back saying that SFERS Board had directed SFERS staff to “study” the divestment. But she offered no explanation to Avalos of when SFERS staff would conclude its “study,” and when SFERS’ Board would actually start its process to begin fossil fuel divestment.

She coyly testified that Jeremy Grantham is an expert in investments and an advocate of trying to understand when to divest from fossil fuels. This is the same Grantham who is a legendary hedge fund investor and founder of the $100 billion funds manager, GMO. And it’s the same GMO in which she invested in, in August 2011. It’s been reported that Grantham expects fossil fuels investments will undergo rapid divestment over the next 10 to 40 years, and it will completely replace fossil fuels energy in favor of renewable alternate energy sources.

It is completely unclear why Paskin-Jordan is stalling SFERS divestment from fossil fuels, but some observers worry that her investments in Grantham’s GMO Quality Fund — the one she invested in, in 2011 — may be slowing things down.

Lamely, she claimed

that as proof of her interest in divesting from fossil fuels,

she drives a Prius. Oh, please!

Lamely, she claimed

that as proof of her interest in divesting from fossil fuels,

she drives a Prius. Oh, please!

Experience With Hedge Funds

Corporate-controlled Mayor Ed Lee and his billionaire financier pals want to get their hands on the City employees’ pension funds by pushing investing in hedge funds that have obscene fees, using fee speculators and union busters who want to grab pension funds with their sticky fingers. Mr. Mayor reappointed Wendy Paskin-Jordan to SFERS’ Board for a five-year term, despite her financial conflicts of interest and her probable malfeasance. She also stated on the Labor Video Project’s You Tube video that she wants to invest in good “hedge funds.” It’s not known whether she has hedge investments in her $674 million Paskin Capital Advisors, LLC fund.

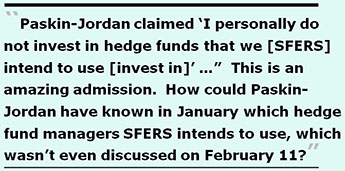

Perhaps in a preemptive move, she surprisingly said at the end of the video segment: “I personally do not invest in hedge funds that we [SFERS] intend to use [invest in] …”

This is an amazing

admission, if you think about it. She said this on January 17,

nearly a month before

the SFERS Board voted on February 11 to approve investing in hedge

funds. How could Paskin-Jordan have known in January which hedge

fund managers SFERS intends to use, which wasn’t even discussed

on February 11 when SFERS’ Board approved investing in hedge

funds?

This is an amazing

admission, if you think about it. She said this on January 17,

nearly a month before

the SFERS Board voted on February 11 to approve investing in hedge

funds. How could Paskin-Jordan have known in January which hedge

fund managers SFERS intends to use, which wasn’t even discussed

on February 11 when SFERS’ Board approved investing in hedge

funds?

That decision point hasn’t been reached, and won’t be (reportedly) for months.

She also claimed on the video “I don’t have a huge amount of experience with hedge funds.” It’s unclear what rationale she exercises when deciding whether to personally invest in hedge funds.

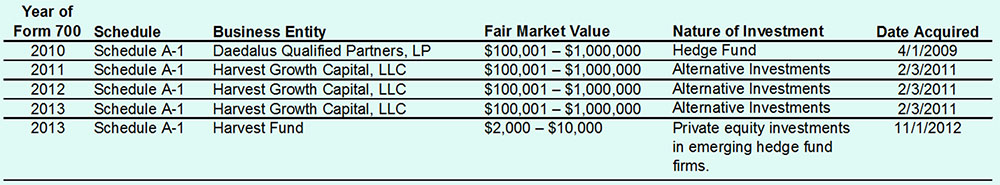

Paskin-Jordan’s Form 700’s on file with the Ethics Commission reveal she has had some experience with hedge funds:

As reported elsewhere, “alternative investments” is a financial investing buzz word that often — though not exclusively — includes hedge funds.

Investopedia.com reports that most alternative investment assets are held by institutional investors or accredited, high-net-worth individuals because of their complex nature, limited regulations, and relative lack of liquidity. Alternative investments include hedge funds, managed futures, real estate, commodities and derivatives contracts. For its part, Harvest Growth Capital does not state on its web site what types of “alternative investment” vehicles it uses.

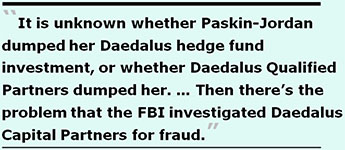

Curiously, Paskin-Jordan reported on her annual Form 700 for the period ending December 31, 2010 her April 2009 investment of between $100,001 and one million dollars in the Daedalus Qualified Partners hedge fund. At that point, she had held the investment for 21 months — a year and nine months. Oddly, within the next 12 months, the Daedalus investment mysteriously vanished from her annual Form 700 for 2011 for the period ending December 31, 2011.

Form 700 instructions for Schedule A-1 stipulate that the disposal of personal investments must be reported, including the date disposed of. There’s no record in Paskin-Jordan’s Form 700’s indicating when she disposed of her Daedalus investment. The Form 700 instructions clearly state that “[a] … disposed of date is only required [when an investment interest] is entirely disposed of during the reporting period.”

When the investment

vanished from her Form 700 for the period ending December 31,

2011, the Form 700 instructions are very clear that any remaining

investment (assuming any previous partial disposals) or the entire

disposal must be reported with the date of the final “entirely

disposal of.” Why Paskin-Jordan failed to report the date

on which she appears to have finally disposed of the Daedalus

hedge fund investment is another symptom of how Paskin-Jordan

may be gaming the system and flouting disclosure rules.

When the investment

vanished from her Form 700 for the period ending December 31,

2011, the Form 700 instructions are very clear that any remaining

investment (assuming any previous partial disposals) or the entire

disposal must be reported with the date of the final “entirely

disposal of.” Why Paskin-Jordan failed to report the date

on which she appears to have finally disposed of the Daedalus

hedge fund investment is another symptom of how Paskin-Jordan

may be gaming the system and flouting disclosure rules.

It is unknown whether Paskin-Jordan dumped her Daedalus hedge fund investment, or whether Daedalus Qualified Partners dumped her.

What is known is that the California Secretary of State’s web site reports that Daedalus Qualified Partners has a status of “canceled” (i.e., no longer an active registered business in the State of California). Unfortunately the Secretary of State’s web site doesn’t indicate the date when Daedalus Qualified Partners was changed to “canceled” or why. The Secretary of State’s web site indicates that a “John S. Osterweis” formerly located at One Maritime Plaza in San Francisco as being Daedalus Qualified Partners’ agent for service or process.

Another document available on the CorporationWiki web site includes an entity-relationship diagram showing the relationships between Daedalus Qualified Partners; Osterweis Capital Management, LLC (which remains an active company according to the Secretary of State); and another outfit called Daedalus Capital Partners.

It turns out that the FBI investigated Daedalus Capital Partners for fraud, a case that involved:

It gets worse. As

recently as May 23, 2014, the Chicago Tribune reported that the

Illinois Securities Department had charged Daedalus Capital, LLC’s

founder and chief investment officer Stephen Messiah Coleman with

fraud, claiming in a civil action that the money manager sold

improper investments and acted as an unlicensed adviser. Illinois’

action followed on the heels of a fraud case in Missouri, which

had also prohibited Coleman from selling securities after Missouri’s

securities commissioner found that Coleman had committed fraud.

It gets worse. As

recently as May 23, 2014, the Chicago Tribune reported that the

Illinois Securities Department had charged Daedalus Capital, LLC’s

founder and chief investment officer Stephen Messiah Coleman with

fraud, claiming in a civil action that the money manager sold

improper investments and acted as an unlicensed adviser. Illinois’

action followed on the heels of a fraud case in Missouri, which

had also prohibited Coleman from selling securities after Missouri’s

securities commissioner found that Coleman had committed fraud.

The relationships, if any, between various Daedalus Capital, LLC outfits in Missouri, Illinois, and perhaps elsewhere; Daedalus Capital Partners; and Daedalus Qualified Partners, LP, is not yet clear. But what is clear, is that there have been multiple allegations of fraud against some of these financial investment companies.

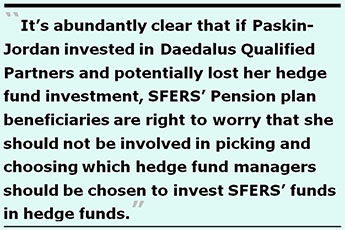

And it’s abundantly clear that if Paskin-Jordan invested in Daedalus Qualified Partners and potentially lost her hedge fund investment, SFERS’ Pension plan beneficiaries are right to worry that she should not be involved in picking and choosing which hedge fund managers should be chosen to invest SFERS’ funds in hedge funds. If she was unable to pick a sound hedge fund manager using her personal funds, Plan beneficiaries have a damned good reason to worry about her ability to pick a “good hedge fund” using their pension funds.

As for her experience with hedge funds, her Form 700’s reveal she has had “experience” with between $200,002 and $2 million invested in hedge funds or hedge funds masquerading as “alternative investments.” This invites the question of whether she is telling the truth about how much experience she has with hedge funds.

Schedule A-2 involves reporting of business-related investments, as opposed to personal investments on Schedule A-1. Paskin-Jordan lists a single, aggregate report for Paskin Capital Advisors, not detailed, individual investment reports made by her firm, so it is not known what level of expertise she has with hedge funds for her business clients.

The Board of Supervisors

unanimously approved her reappointment, despite her support for

hedge funds and the many financial conflicts of interest which

are now bottled up in the Ed Lee-controlled Ethics Commission.

The Board of Supervisors

unanimously approved her reappointment, despite her support for

hedge funds and the many financial conflicts of interest which

are now bottled up in the Ed Lee-controlled Ethics Commission.

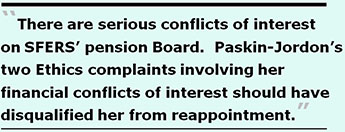

At the same time, there are serious conflicts of interest on SFERS’ pension board. Wendy Paskin-Jordon’s two Ethics complaints involving her financial conflicts of interest - since she is a sales person for financial securities - should have disqualified her from reappointment. Why should she be on SFERS’ Board when it appears she may be using her position to financially benefit herself or benefit her clients?

This begs the question: Which oversight body will seriously consider and dispose of the ethics allegations against Paskin-Jordan? The Board of Supervisors? The Ethics Commission? The Retirement Board?

Clearly it’s not the Board of Supervisors, which failed miserably to conduct a meaningful investigation of Paskin-Jordan’s conflicts of interest and her questionable behavior. The Ethics Commission, for its part, will undoubtedly drag its feet investigating the two ethics complaints filed against her, and it will take a year or longer for Ethics to rule on the two complaints.

That leaves the Retirement

Board. Under Roberts Rules of Order, and various codes of ethics

that apply to SFERS Commissioners, the Retirement Board could

mount its own investigation under provisions to censure Board

members. Since her behavior reflects so negatively on SFERS’

Board, a reasonable person would assume the Board would have conducted

its own investigation by now, open to members of the public.

Why hasn’t SFERS’ Board moved to protect its own reputation?

That leaves the Retirement

Board. Under Roberts Rules of Order, and various codes of ethics

that apply to SFERS Commissioners, the Retirement Board could

mount its own investigation under provisions to censure Board

members. Since her behavior reflects so negatively on SFERS’

Board, a reasonable person would assume the Board would have conducted

its own investigation by now, open to members of the public.

Why hasn’t SFERS’ Board moved to protect its own reputation?

It is time to protect the City’s pension fund by eliminating

all conflicts of interest. Paskin-Jordan could help out by doing

the only ethical thing: She should resign from SFERS’ Board,

immediately.

Top

Monette-Shaw is an open-government accountability advocate, a

patient advocate, and a member of California’s First Amendment

Coalition. He received the Society of Professional Journalists-Northern

California Chapter’s James

Madison Freedom of Information Award

in the Advocacy category in March 2012. Feedback: monette-shaw@westsideobserver.