Westside Observer

Westside Observer July 2014 at www.WestsideObserver.com

Laguna Honda Hospital: “where Do They Go?”

The Big Squeeze: Dys-Integration of “Old Friends”

Article Printer-friendly

PDF file

Westside Observer

Westside Observer

July 2014 at www.WestsideObserver.com

Laguna

Honda Hospital: “where Do They Go?”

The Big Squeeze:

Dys-Integration of “Old Friends”

by Patrick Monette-Shaw

Are our “Old Friends — the elderly and people with disabilities — being dys-integrated right out of San Francisco, along with other populations being squeezed out and displaced out-of-county? Where do they all go?

That’s one question.

Other questions involve myriad problems at Laguna Honda Hospital, including broad service reductions. Then there’s the question of why the City racked up $3.8 million dollars in City Attorney time and expenses pursuing a lawsuit that recovered just $15 million of $70 million in alleged design and construction errors in the rebuild of LHH’s new facility, netting just $11 million after City Attorney time and expenses.

In the Westside Observer’s March issue, former Laguna Honda physicians Maria Rivero and Derek Kerr summarized Laguna Honda Hospital’s (LHH) changing patient demographics, and posed thoughtful questions, including:

Kerr and Rivero’s questions are astute, given news that San Francisco’s Health Commission and the Department of Public Health are relying on a May 2011 analysis — now three years old, and out of date — prepared by Resource Development Associates, which DPH had commissioned, that projected then a shortage of 700 skilled nursing facility (SNF) beds in San Francisco just over 30 years from now. Given the analysis is sadly out of date, is the 700-bed shortage now much worse?

The report noted

that the number of San Franciscans over the age of 75 is expected

to increase by almost two-thirds over the next 20 years. Data

presented to Supervisor David Campos on March 20 by the Department

of Aging and Adult Services shows that just six years from now in 2020,

San Francisco’s population of residents over the age of 60

will increase by 37,761 — a 26 percent increase. During the

same six years, San Franciscans over the age of 85 will increase

by 24,600 (a 73 percent increase), representing two-thirds of

the increase of those over the age of 60.

The report noted

that the number of San Franciscans over the age of 75 is expected

to increase by almost two-thirds over the next 20 years. Data

presented to Supervisor David Campos on March 20 by the Department

of Aging and Adult Services shows that just six years from now in 2020,

San Francisco’s population of residents over the age of 60

will increase by 37,761 — a 26 percent increase. During the

same six years, San Franciscans over the age of 85 will increase

by 24,600 (a 73 percent increase), representing two-thirds of

the increase of those over the age of 60.

Factor in the current trend of conversion of long-term care SNF beds to short-term care SNF beds throughout California, exacerbating the shortage of long-term care SNF beds.

On March 20, the State of California’s long-term care Ombudsman for San Francisco — who has jurisdiction involving oversight of skilled nursing facilities and residential care homes — Benson Nadell, testified to the Board of Supervisors Neighborhood Services and Safety Committee, saying:

As in: Squeeze. Squeeze. Squeeze out-of-county.

Where will all of these people go, and how many will be displaced out-of-county? And what about reports of other troubling issues involving LHH?

Patient Demographic Shifts Displace Frail Elderly

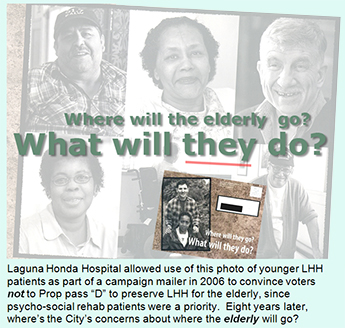

In March, Kerr and

Rivero reported that for the first time in memory, women and the

elderly over age 75 have become minorities in LHH. In 1999, when

voters approved the bonds to rebuild LHH for our “Old Friends,”

fully 56% of LHH’s residents were female. By 2013, female

patients dropped by 15% to just 41%, while the percentage of male

patients increased 15%, from 44% to 59%. The percentage of patients

over the age of 65 dropped 20% between 1999 and 2013, from 67%

to just 47%. In 1999, those over the age of 75 was 52%. Not any

more, due to a variety of changes at LHH.

In March, Kerr and

Rivero reported that for the first time in memory, women and the

elderly over age 75 have become minorities in LHH. In 1999, when

voters approved the bonds to rebuild LHH for our “Old Friends,”

fully 56% of LHH’s residents were female. By 2013, female

patients dropped by 15% to just 41%, while the percentage of male

patients increased 15%, from 44% to 59%. The percentage of patients

over the age of 65 dropped 20% between 1999 and 2013, from 67%

to just 47%. In 1999, those over the age of 75 was 52%. Not any

more, due to a variety of changes at LHH.

In January, the Department of Public Health finally announced that it would begin providing data on the number of Laguna Honda patients being discharged out of county beginning in 2014 and going forward. DPH reported in January that 12% of discharges from LHH between September and December 2013 were to out-of-county locations.

But it has adamantly refused to provide historical data on the number of patients discharged from, or diverted from admission to, LHH that were subsequently discharged or diverted out-of-county since 2003.

Just two weeks after Kerr’s article in the March Observer, DPH and the Department of Aging and Adult (DAAS) services made a pitch before the Board of Supervisors Neighborhood Services and Safety Committee on March 20, requesting a $3 million increase in FY 14-15 to funding for the so-called Community Living Fund that was established to provide community-based “supports” to prevent placement in long-term care skilled nursing facilities, or provide services post-discharge from a SNF, or for those who choose to “age in place” at home. While Hinton and Garcia have been unwilling to release data on out-of-county discharges to Supervisor Campos for now going on three months, they nonetheless had the chutzpa to request $3 million in additional funding for the “Community Living Fund,” without telling Campos where the elderly are being discharged to.

Mayor Ed Lee — despite hobnobbing with billionaire backer Ron Conway — apparently didn’t lift a finger and didn’t request the $3 million increase for the Community Living Fund in his budget submission to the Board of Supervisors. Of the $23 million in adjustments the Board of Supervisors Budget and Finance Committee made re-arranging the Mayor’s FY 14-15 budget, the Community Living Fund received an increase of just $200,000. Of $18.4 million in adjustments the Budget Committee made to the Mayor’s second-year, FY 15-16 budget, the Community Living Fund received nothing.

Admirably, Supervisor David Campos peppered Director of Public Health Barbara Garcia and DAAS’ Executive Director, Anne Hinton on discharge location data on March 20 in an effort to learn whether patients are being “integrated” into San Francisco communities, or whether they are being “integrated” in out-of-county communities. Both Hinton and Garcia did their level best to claim they had no way of tracking discharge data by location and type of facility, and that the aggregate data (scrubbed of any patient identifiers) might be protected somehow under the HIPPA law protecting patient’s medical records, a claim that is complete nonsense. DPH had already provided before March a limited amount of aggregate out-of-county discharge data for 2013, without violating HIPPA.

Hinton at first asserted

during Campos’ March 20 hearing that she would have no way

of knowing any discharge or diversion data, until this reporter

testified during Campos’ hearing that under the Chambers

settlement agreement, a Diversion and Community Integration Program

(DCIP) was required by the U.S. Department of Justice. I testified

that both DPH and DAAS have seats on the DCIP screening panel

that reviews admission packets for requests for admission to LHH,

a fact Hinton had to have known.

Hinton at first asserted

during Campos’ March 20 hearing that she would have no way

of knowing any discharge or diversion data, until this reporter

testified during Campos’ hearing that under the Chambers

settlement agreement, a Diversion and Community Integration Program

(DCIP) was required by the U.S. Department of Justice. I testified

that both DPH and DAAS have seats on the DCIP screening panel

that reviews admission packets for requests for admission to LHH,

a fact Hinton had to have known.

Hinton quickly changed her tune with Campos, creatively claiming she hadn’t understood the question Campos had asked her. She remained disingenuous about availability of the discharge data.

Indeed, it turns out that it was DAAS that had contracted with a company named RTZ Associates to develop a database for the DCIP component. Since 2003, RTZ has been paid at least $5.6 million to develop 10 to 12 different components of the SF GetCare database (FY 03-06, FY 07-09, FY 10-14). How Hinton claimed to Supervisor Campos that she would have no way of knowing this data, when it was her department that had contracted for the DCIP component and continues to pay annual maintenance fees, is not known, but she may have deliberately and intentionally mislead Campos.

Mere Trickle of Data

Following a month

in which Supervisor Norman’s Yee’s legislative aide

Olivia Scanlon proved to be not at all helpful in trying to obtain

out-of-county discharge data from DPH and DAAS, on April 29 Campos’

legislative aide Carolyn Goossen submitted a list of seven explicit

questions (see Postscript at end of document) on behalf of Supervisor

Campos to Hinton and Garcia seeking data on both discharges from

LHH and diversion from LHH admission data between 2007 and May

2014. The seven-year period is significant since the Chambers

settlement agreement was adopted in 2007.

Following a month

in which Supervisor Norman’s Yee’s legislative aide

Olivia Scanlon proved to be not at all helpful in trying to obtain

out-of-county discharge data from DPH and DAAS, on April 29 Campos’

legislative aide Carolyn Goossen submitted a list of seven explicit

questions (see Postscript at end of document) on behalf of Supervisor

Campos to Hinton and Garcia seeking data on both discharges from

LHH and diversion from LHH admission data between 2007 and May

2014. The seven-year period is significant since the Chambers

settlement agreement was adopted in 2007.

True to form, Garcia and Hinton on behalf of DPH and DAAS dragged their feet. Kelly Hiramoto, the Acting Director of Transitions for DPH’s San Francisco Health Network, finally responded 30 days later on May 29 to Campos on behalf of DPH. Hinton appears to have never responded to Campos. Hiramoto was ostensibly responding on behalf of Director Garcia, and perhaps Hinton.

Hiramoto claimed on May 29 that “The data that was collected is incomplete. The software program designed to capture the data did not work as designed.” When pressed for details, Nancy Sarieh, DPH’s public information officer, wildly claimed on June 9 that the software that didn’t work as designed was the SF GetCare database RTZ Associates has been paid $5.6 million to develop and maintain between 2003 and 2014.

If the software doesn’t function as designed, why have DPH and DAAS continued to pay for annual maintenance and support to the tune of $5.6 million during the past decade?

Concerned about the potential for reputational harm to RTZ, I contacted RTZ’s founder, Dr. Rick Zawadski — who is a nationally-recognized authority on long-term care policy — for comment. Zawadski said on June 23, “RTZ Associates stands behind the functionality and integrity of the software we have developed for the City of San Francisco. Any data fields related to LHH Diversions requested by the City of San Francisco are fully functional and work as designed.”

So much for DPH’s nonsense that the software doesn’t work.

DPH’s Misinformation Presented to Supervisor Campos

For good measure, Hiramoto tossed into her May 29 response to Supervisor Campos, “We did not collect the data in a reportable manner for the years not included.” Hiramoto provided just three years worth of data to Campos, but excluded seven years of data, claiming the data wasn’t in a “reportable” format. Hiramoto offered no explanation of how three years of the data could be in a reportable format, but the other seven years were not.

She did send Campos

a three-inch, three-ring binder containing reports from the Targeted

Case Management (TCM) program that was also required by the Chambers

settlement agreement, and two LHH-Joint Conference Committee reports

already provided to this columnist, claiming the binder covered

the time period requested. That claim was also untrue, since the

reports covered only January 2006 to May 2009, and excludes both

data between March 2004 and December 2005 after the Targeted Case

Management program was implemented, and excludes any data whatsoever

between June 2009 and June 2014.

She did send Campos

a three-inch, three-ring binder containing reports from the Targeted

Case Management (TCM) program that was also required by the Chambers

settlement agreement, and two LHH-Joint Conference Committee reports

already provided to this columnist, claiming the binder covered

the time period requested. That claim was also untrue, since the

reports covered only January 2006 to May 2009, and excludes both

data between March 2004 and December 2005 after the Targeted Case

Management program was implemented, and excludes any data whatsoever

between June 2009 and June 2014.

The data that DPH provided to Supervisor Campos’ office only in hardcopy format included TCM monthly reports for eight months in 2006 (the May, June, October, and November monthly reports for 2006 were missing), nine months in 2007 (the May, October, and November monthly reports for 2007 were missing), 11 months in 2008, (the November monthly report for 2008 was missing), and just three reports for 2009, including one report for January, a quarterly report for January-February-March, and a third report for April and May 2009.

The hardcopy printouts supplied to Campos show that between January 2006 and May 2009 there had been at least 143 TCM clients discharged from LHH and an untold number of non-TCM program discharges. Luckily, historical trend-line graphs embedded in the limited reports provided to Campos do show that between March 2004 and May 2009 there were a total of 671 TCM admissions and a total of 262 TCM discharges. And the reports show that in just the two-year period between February 2007 and January 2009 there were another 188 SFGH patients diverted from admission to LHH.

There was no data provided showing diversions from LHH from hospitals and other facilities other than SFGH, but since the TCM and DCIP programs are thought to have tracked referrals from other referring facilities, and patients requesting LHH placement from their homes, there had to have been other diversions from LHH admission between 2007 and 2009, in addition to the 188 SFGH patients diverted from LHH admission that we know about.

And Hinton and Garcia provided no data whatsoever about the number of SFGH or other referring facility “diversions” from LHH admission during the ensuing five-year period between 2009 and 2014.

Between the total

TCM discharges and the SFGH patients diverted, we’re talking

about at least 452 patients that DPH and DAAS are unwilling to

admit how many were discharged out of county. As Kerr and Rivero

asked, where do these patients go? If the Targeted Case Management

program and the Diversion and Community Integration Programs were

so successful at placing patients back into the community, why

are DPH and DAAS so desperately trying to hide the out-of-county

discharge data from both San Francisco’s citizens, and our

very Board of Supervisors we expect to make informed policy decisions?

Between the total

TCM discharges and the SFGH patients diverted, we’re talking

about at least 452 patients that DPH and DAAS are unwilling to

admit how many were discharged out of county. As Kerr and Rivero

asked, where do these patients go? If the Targeted Case Management

program and the Diversion and Community Integration Programs were

so successful at placing patients back into the community, why

are DPH and DAAS so desperately trying to hide the out-of-county

discharge data from both San Francisco’s citizens, and our

very Board of Supervisors we expect to make informed policy decisions?

Could it be these patients are not being “integrated” into San Francisco communities, but are being integrated into out-of-county communities?

Can it be, as observers suspect, that LHH patients and diverted patients are being dumped out-of-county along with the vast displacement of long-term San Franciscan’s displaced out-of-county caused by the hot real estate market? How many people were diverted from admission to LHH over the past decade? Where did they go?

As of the end of June, DPH continues to refuse providing even a simple list of the field names included in the SF GetCare, TCM, and DCIP modules of RTZ’s database systems custom-developed for DPH and DAAS, claiming there were “no responsive records” to a request for the underlying “data dictionary” listing the field names. That’s hogwash, too, since every database worth its salt has an easily-printable data dictionary underlying the database architecture, as any first-year information technology student knows is true.

RTZ’s Robust System Components

On June 9, Nancy

Sarieh, Public Information Officer (PIO) for DPH replied to a

follow-up public records request that “the software program

involved that did not work as designed is SF GetCare.” It

appears Sarieh didn’t know what she was talking about, and

just grabbed spin control out of her PIO kit-bag, clueless.

On June 9, Nancy

Sarieh, Public Information Officer (PIO) for DPH replied to a

follow-up public records request that “the software program

involved that did not work as designed is SF GetCare.” It

appears Sarieh didn’t know what she was talking about, and

just grabbed spin control out of her PIO kit-bag, clueless.

In October 2003, DPH first contracted with RTZ Associates to streamline Laguna Honda Hospital’s discharge planning processes and increase access to community-based services, by developing a software application called “SF GetCare” that initially included a core discharge planning module rolled out in 2003.

Enhancements implemented across the past decade have been vast, and significant. It has evolved into a comprehensive, robust, data information system to coordinate services across various San Francisco county programs, in collaboration with both the Department of Public Health and the Department of Aging and Adult Services.

“SF GetCare” was expanded to include a DPH housing placement component, a component upgraded in FY 09-10, again in FY 12-13, and apparently upgraded again in FY 13-14. The component includes a searchable directory of housing resources for the Department of Public Health’s “Direct Access to Housing” program. An optional upgrade for hospital discharge planners and community-based case managers to allow on-line applications for the Direct Access to Housing program was developed, but it is not known whether the Direct Access to Housing application form was added in FY 13-14 to the housing placement component currently used for other components of DPH-supported housing programs.

Another component of SF GetCare is an SFGH placement component to support the identification and disposition of discharge-ready patients to allow nurses, social workers, psychiatrists, eligibility and placement staff, and others to manage the discharge of patients from SFGH, and identify discharge placement settings to meet patient needs and preferences.

During FY 09-10,

RTZ designed, tested, and deployed a module at its own expense

as an in-kind contribution, an “Administrator on Duty”

component for LHH to support hospitalwide communications across

the three shifts of staff. LHH has since assumed responsibility

for support of this module, but RTZ continues to provide bug fixes

until funding for the full features for this component is found.

During FY 09-10,

RTZ designed, tested, and deployed a module at its own expense

as an in-kind contribution, an “Administrator on Duty”

component for LHH to support hospitalwide communications across

the three shifts of staff. LHH has since assumed responsibility

for support of this module, but RTZ continues to provide bug fixes

until funding for the full features for this component is found.

In July 2008, the Department of Aging and Adult Services contracted with RTZ to develop an information system to support the operational needs of the then newly-developed “Diversion and Community Integration Program” mandated by the Chambers settlement agreement against the City and LHH, and to meet reporting requirements, presumably reports to the U.S. Department of Justice to monitor compliance with the Chambers settlement agreement. The DCIP component includes a discrete sub-system within SF GetCare that pulls information from LHH, Targeted Case Management, and Community Living Fund datasets to create an integrated client management systems. During FY 10-11, RTZ enhanced the DCIP component.

In September 2009, the Department of Aging and Adult Services again contracted with RTZ to develop the California GetCare system to meet local data collection and management needs around state and federal reporting for three specialty-funded services. In FY 10-11 RTZ began developing an intake and assessment (I&A) module to expand the initial features of SF Get Care.

By May 2012, DAAS had determined it needed to expand the I&A module to eliminate duplication of assessments and data entry activities. The new system, launched in March 2013, allows DAAS to complete a single assessment for consumers who need to receive multiple community-based services, including transitional care, community living fund services, home-delivered meals, and in-home supportive services. Phase 1 of a system to allow consumers, caregivers, and discharge planners to create personal accounts to complete intake applications for these multiple community-based services was launched in April 2013.

DAAS had RTZ add a new “case management” component to SF GetCare for community-based case managers to track progress notes, various client assessments, service plans, and medication management, which may have been added to the contract with RTZ.

In April 2012, DAAS contracted with RTZ to develop a “Transitional Care Program” system to support the operational needs and reporting requirements to track “coaching” and care coordination services for patients being discharged from acute-care hospital settings for “Transition Specialists.” A “list bill administration” enhancement was added to this component to ensure that DAAS receives reimbursement from vendors approved by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for each case.

An optional, already-implemented,

or a pending enhancement to the RTZ suite of system components

includes a new component to assist managing “behavioral health”

— formerly known as “mental health services” —

services that may have been included in the City’s contract

with RTZ Associates during FY 2013-2014.

An optional, already-implemented,

or a pending enhancement to the RTZ suite of system components

includes a new component to assist managing “behavioral health”

— formerly known as “mental health services” —

services that may have been included in the City’s contract

with RTZ Associates during FY 2013-2014.

Ms. Hiramoto’s and Ms. Sarieh’s claims the RTZ software didn’t “work as designed” is nonsense, in part because of the robust components added to the SF GetCare database over the past decade.

Reasonable observers are now wondering whether the Community Living Fund might have received its full $3 million requested increase, had DPH and DAAS not stalled so long being completely evasive about out-of-county discharge data.

Pathetic Resolution to a $70 Million Lawsuit

In 2011, the City of San Francisco filed a Superior Court case against Anshen + Allen and Stantec Architecture alleging $70 million in defective performance, and design and construction errors on the rebuild of Laguna Honda Hospital. The case was subsequently transferred to Alameda County when the architects’ lawyers claimed they couldn’t receive a fair trial in San Francisco.

On November 19, 2013,

the Board of Supervisors considered an initial proposed settlement

with Stantec estimated to recover just $19 million of the alleged

$70 million in design and construction errors. By May 2014, the

proposed settlement agreement shrank to just $15 million, representing

just 21 percent of the $70 million in deficiencies the City had

initially alleged.

On November 19, 2013,

the Board of Supervisors considered an initial proposed settlement

with Stantec estimated to recover just $19 million of the alleged

$70 million in design and construction errors. By May 2014, the

proposed settlement agreement shrank to just $15 million, representing

just 21 percent of the $70 million in deficiencies the City had

initially alleged.

On October 3, 2013, City Controller Ben Rosenfield advised the Citizen’s General Bond Oversight Committee (CGOBOC, pronounced “go-bok”) that if debt service on a bond measure is not paid off, and if “surplus funds” of a bond measure (perhaps recovered during lawsuits) subsequently surface, it may become a policy matter for the Board to determine how to use surplus funds, rather than returning them to the City’s General Fund. Rosenfield noted that if there is outstanding debt, remaining balances can be applied to reduce debt service. If the debt service is paid off, the surplus can be applied to the General Fund. Trouble is, the LHH rebuild bond measure debt has not been paid off.

The $15 million purportedly recovered as a result of the lawsuit should have more appropriately been applied to a) Paying down the debt on the general obligation bonds voters approved to construct the new LHH; b) Correcting remaining construction problems at LHH, or re-instating elements of the proposed rebuild that were eliminated from the project scope during “scope reductions,” including the ADA-accessible pathway on the top half of the hill to the old main entrance the LHH’s now administrative wings that has still not been constructed; or c) Reserving the funds for building desperately-needed assisted living facilities promised to voters in the November 1999 voter guide when voters approved Prop A to rebuild LHH.

The Department of Public Works project manager for the LHH Rebuild project, John Thomas, testified during the October 15, 2013 meeting of the full Health Commission, that the City’s lawsuit against Stantec Consulting Services Inc. and Stantec Architecture Inc. to recover $70 million in design and construction errors from the architects hired to design the LHH replacement facility — Anshen + Allen, which was subsequently acquired by Stantec Consulting — was moved to Alameda County Superior Court, with the lawsuit being “fronted” using funds from the LHH Rebuild bond measure.

Thomas’ testimony

was a shocking revelation that bond money for a capital improvement

project was being diverted from actual construction to legal costs

instead, an accounting switcheroo that observers believe is not

permitted under bond financing rules. Legal fees for lawsuits

should come from subaccounts set up in the General Fund to handle

legal cases.

Thomas’ testimony

was a shocking revelation that bond money for a capital improvement

project was being diverted from actual construction to legal costs

instead, an accounting switcheroo that observers believe is not

permitted under bond financing rules. Legal fees for lawsuits

should come from subaccounts set up in the General Fund to handle

legal cases.

After Mayor Ed Lee finally signed the Board of Supervisors ordinance passed June 10 on a “second reading” to settle the lawsuit, the City Attorney’s Office admitted on June 24 that it had spent $3.8 million in City Attorney time and expenses — including 11,400 hours of City Attorney time between 2011 and 2014 — mounting and pursuing the lawsuit.

One remaining question is whether the $3.8 million legal tab “fronted” from the bonds to rebuild LHH was restored to the LHH rebuild project budget. Another question is whether the October 2013 proposed settlement of $19 million was reduced to just $15 million, in order to set aside the $3.8 million in City legal costs.

After all, any legal fees diverted from the bond to cover this lawsuit should also be returned to the project budget to restore features to the replacement hospital that were eliminated during scope reduction.

Settling for just 21% of the design and construction errors is a slap in the face to San Franciscans, who are in effect being asked to shoulder over $50 million in design and construction errors on this replacement project, as if $50 million is chump change and not of concern to voters. Surely, Anshen + Allen / Stantec have more culpability for the additional $50 million variance in design and construction errors than it acknowledged.

It appears that the Board of Supervisors took no action and allowed the $15 million settlement to be placed into the General Fund.

Broad Service Reductions at LHH

Service reductions at Laguna Honda have been underway for at least a decade, when the hospital began focusing on short-term care, rather than on long-term care. Since moving into its replacement facility in December 2010, LHH’s focus on short-term care has accelerated.

As Ombudsman Benson Nadell testified to Supervisor Campos on March 20:

Nadell added that

there are many patients who cannot participate in the Department

of Public Health’s system centered on providing services

in the community rather than at Laguna Honda. Once patients are

discharged from rehabilitation services, they often cannot participate

in programs created to supplant care at LHH.

Nadell added that

there are many patients who cannot participate in the Department

of Public Health’s system centered on providing services

in the community rather than at Laguna Honda. Once patients are

discharged from rehabilitation services, they often cannot participate

in programs created to supplant care at LHH.

As noted at the beginning of this article, Nadell testified: “This is not just [about] giving people the option of not going to nursing homes, there aren’t any [nursing homes].”

Short-Term 60-Day Rehabilitation

Data presented to the Health Commission on January 28, 2014 illuminates LHH’s focus on short-term care. Commissioners were informed that LHH has just 49 short-stay skilled nursing facility (SNF) physical medicine rehabilitation beds.

In the three-year period between 2011 and 2013, the focus on “get ’em in, then get ’em out” resulted in an increase of new admissions to the hospital from 380 admissions in 2011, to 449 admissions in 2013. The behind-the-scenes operating philosophy of the physiatrists — a physician specialty focusing on physical medicine rehabilitation — has been for over a decade-and-a-half, “if the patient is walking, get them out.”

It’s a philosophical mind-set often dismaying to LHH clinicians in other specialties who believe that many patients who had re-learned to walk still had significant unresolved rehabilitation needs, such as upper-body rehabilitation or speech pathology needs to prevent choking while eating, and were being discharged prematurely, potentially leading to re-admission or poorer post-discharge outcomes.

It is not known whether LHH’s Chief of Rehabilitation Services, Dr. Lisa Pascual, and LHH’s physiatry physicians are permitted to determine during medical records of review of rehabilitation admission referrals whether patients who exceed the 60-day short-term (or formerly, the longer 90-day) rehab length of stay may be denied admission, and whether they have, in fact, denied admission of patients needing longer rehabilitation courses of treatment.

But what is known,

is that at least one patient at SFGH who had sought admission

to LHH for rehabilitation services was denied admission in recent

memory, told that he needed “too much” rehabilitation.

He languished for months on an acute-care SFGH unit at acute-care

hospital billing rates until he was discharged out-of-county in

2011 to a skilled nursing facility in Antioch specializing in

dementia patients, socially and culturally isolated from friends

and family, and with nobody to communicate with, given the number

of dementia patients.

But what is known,

is that at least one patient at SFGH who had sought admission

to LHH for rehabilitation services was denied admission in recent

memory, told that he needed “too much” rehabilitation.

He languished for months on an acute-care SFGH unit at acute-care

hospital billing rates until he was discharged out-of-county in

2011 to a skilled nursing facility in Antioch specializing in

dementia patients, socially and culturally isolated from friends

and family, and with nobody to communicate with, given the number

of dementia patients.

No data was presented to the Health Commission indicating what becomes of patients who require long-term rehabilitation longer than 60 days, and whether those rehab patients are diverted to the few remaining facilities that provide longer-term rehabilitation. Where do patients who have suffered traumatic brain injuries and need 90-day rehab care go? Out of county?

Functional Maintenance Program Moved to Nursing

Leading up to 1999, the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division investigated reports of neglect and premature functional decline of patients on LHH’s long-term care wards.

As a result, LHH hired three rehabilitation therapists, one each in Physical Therapy, Occupational Therapy, and Speech Pathology, who were charged with developing a “functional maintenance program” (also known as “restorative care”) to address the DOJ’s concerns about patient neglect and premature physical decline.

Following a year

researching best practices and developing a staffing proposal,

four Rehabilitation Therapy Aides were hired in 2000 for a Restorative

Care Level I program centralized in the Rehabilitation Services

Department, supervised by licensed rehabilitation therapists.

A separate, but companion, Restorative Care Level II program was

created in the Nursing Department to provide unit-based daily

therapeutic modalities supervised by nurses.

Following a year

researching best practices and developing a staffing proposal,

four Rehabilitation Therapy Aides were hired in 2000 for a Restorative

Care Level I program centralized in the Rehabilitation Services

Department, supervised by licensed rehabilitation therapists.

A separate, but companion, Restorative Care Level II program was

created in the Nursing Department to provide unit-based daily

therapeutic modalities supervised by nurses.

The restorative care program implemented was successful, and the DOJ closed its Civil Rights investigation. The Restorative Care Level I program was expanded over the years, and currently has seven Rehabilitation Therapy Aides.

But that’s suddenly about to change, when the Therapy Aides are transferred from the centralized Rehab Services Department to the Nursing Department on July 1, 2014 and will be based on the wards (“neighborhood” units).

It is not yet clear whether the aides will continue providing Level I rehab treatments as a ward-based program under the supervision of licensed physical medicine clinicians, whether Nursing staff will provide the Level I supervision possibly in violation of State law, or whether those Level I rehab treatment modalities will be eliminated, potentially angering the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division and bringing on a new investigation of LHH.

As if preventing premature functional decline of the elderly is no longer of concern to the DOJ, or no longer a core mission of Laguna Honda Hospital.

Health Commission’s Failure Preventing SNF-Bed Crisis

Across the past decade-and-a-half, the Health Commission has held several hearings to consider the negative impact on the reduction of skilled nursing beds by private hospitals in San Francisco. St. Mary’s, St. Francis, CPMC and other hospital-based skilled nursing facilities have either reduced the number of their licensed SNF beds, or have converted them to short-term rehabilitation rather than to longer-term rehabilitation or long-term care.

Yet the Health Commission

has never adopted resolutions asserting that the loss of those

beds would have — and already have

had — detrimental impacts on the health of San Franciscans.

Of course there have been negative impacts, including an untold

number of out-of-county discharges.

Yet the Health Commission

has never adopted resolutions asserting that the loss of those

beds would have — and already have

had — detrimental impacts on the health of San Franciscans.

Of course there have been negative impacts, including an untold

number of out-of-county discharges.

Indeed, the Health Commission never held a public hearing to assess the detrimental impact of eliminating 420 of LHH’s SNF beds from the rebuild of LHH’s replacement facility. Instead, during a closed session of the Health Commission on January 22, 2008, the Health Commission voted to accept the Chambers lawsuit settlement that eliminated LHH’s 420 SNF beds, and did so without any open-session public discussion of the probable detrimental effects such bed elimination would cause throughout San Francisco.

Now six years later, DPH’s Deputy Director and Director of Policy and Planning, Colleen Chawla, presented the Health Commission with an analysis of CPMC’s newest proposed reduction of skilled nursing beds sprung on the City after its Cathedral Hill Hospital project was approved and a deal cut to preserve St. Luke’s Hospital in the Mission District.

Chawla presented Commissioners with a compelling analysis dated June 12, 2014 that projects a shortage of 700 skilled nursing facility (SNF) beds in San Francisco just over 30 years from now, and the detrimental impact the closure of CPMC’s SNF beds will have on San Franciscans.

Chawla astutely notes that a 2012 report issued by San Francisco’s Department of Aging:

Although some of

Chawla’s data are out of date, she’s clearly right that

there will be a detrimental impact.

Although some of

Chawla’s data are out of date, she’s clearly right that

there will be a detrimental impact.

Hopefully, the Health Commission will finally pay close attention to Ms. Chawla’s dire predictions:

Ombudsman Nadell’s Other Concerns

As noted above, Skilled Nursing Facility Obudsman Nadell presented oral testimony to the Board of Supervisors Neighborhood Services and Safety Committee on March 20 that there aren’t any nursing home beds remaining. Although Resource Development Associates’ May 2011 report for DPH reported that by 2050 San Francisco will only have 1,619 SNF beds, Nadell presented a handout to the Board of Supervisors reporting different data.

He asserts that of 2,225 current long-term care SNF beds, approximately 40% have been converted to short-term rehabilitation beds for reasons of cost, taking long-term care beds “off-line.” He notes 920 Medi-Cal certified SNf beds were reassigned to additional rehabilitation utilization. The adjusted total is just 1,305 Medi-Cal beds, not the 1,619 Resource Development Associates calculated three years ago would be available 36 years from now in 2050.

Nadell reports that over the past 20 years, San Francisco has lost over 900 long-term care Medi-Cal beds.

Nadell included the following vignette in his report:

The projection that

San Francisco will be short 700 skilled nursing beds by 2050 —

which Resource Development Associates may not have analyzed three

years ago — may also ignore a key issue involving the number

of licensed beds vs. the number of beds actually “staffed”

or utilized.

The projection that

San Francisco will be short 700 skilled nursing beds by 2050 —

which Resource Development Associates may not have analyzed three

years ago — may also ignore a key issue involving the number

of licensed beds vs. the number of beds actually “staffed”

or utilized.

DPH’s Director of Policy and Planning, Colleen Chawla, presented her June 12, 2014 analysis to the Health Commission, in which she notes that “licensed beds” are the maximum permitted under each facility’s license; “available beds” are those that physically exist and are available for use; and “staffed beds” are those that are set up, staffed, and are being used.

Chawla did not include for Health Commissioner’s edification a table of 14 hospitals in San Francisco listing how many of the total licensed 1,586 hospital-based skilled nursing beds are actually “available beds” vs. “staffed beds,” but she did provide as one example that of 212 currently licensed SNF beds across CPMCs four campuses, it has just 99 “staffed beds,” which CPMC seeks to slash by 24, to just 75 staffed beds. (This is after CPMC cut additional SNF bed capacity earlier in 2014.)

CPMC admits two amazing facts: First, of its current 99 staffed SNF beds, CPMC’s “average daily census” includes just 68 patients, despite having a license for 212 SNF beds. This is a common practice in hospital-based skilled nursing facilities: To keep the average daily census as low as possible.

Second, CPMC testified to the Health Commissioners on June 17 that CMPC’s SNF patients among its average daily census have an average “length-of-stay” of 14 to 15 days — just two weeks — far shorter than the 60-day (two month) short-term rehab at Laguna Honda and far shorter than the previous industry standard of 90-day rehabilitation stays.

It is not yet known

whether any of the three problems — the lower number of overall

staffed beds, the average daily census issue, and the average

length of stays — were factored in to the Resource Development

Associates analysis projecting a shortage of 700 SNF beds just

30 years from now, or whether those three factors may push the

700-bed shortage far higher.

It is not yet known

whether any of the three problems — the lower number of overall

staffed beds, the average daily census issue, and the average

length of stays — were factored in to the Resource Development

Associates analysis projecting a shortage of 700 SNF beds just

30 years from now, or whether those three factors may push the

700-bed shortage far higher.

Exacerbating issues further, Nadell notes, is the loss of board-and-care beds in the City, also fueled by the hot real estate market. Other types of long-term care facilities are also being scaled back.

Following Nadell’s report to Supervisor Campos on March 20, news surfaced that the University Mound Ladies Home — a 72-bed Residential Care Facility for the Elderly (RCFE) located in San Francisco’s Portola neighborhood at 350 University Street that has operated for over 130 years — is evicting its 53 residents effective July 10, most of whom are in their late 80’s or early 90’s.

University Mound’s Board of Trustees — whose president of the Board is Mary Louise Fleming, Laguna Honda Hospital’s former Director of Nursing — issued 60-day eviction notices to residents, family members, and other representatives in early May, indicating the closure was due to insurmountable debt. The board informed residents that the building was closing, citing debt load, and an imbalance of revenue and expenditures.

At a rally in Civic Center Plaza on May 30, San Francisco Supervisor David Campos shared his support for University Mound residents, saying “the City has an obligation to step in.” Campos indicated he was working with the Mayor’s office to add $300,000 to this year’s budget to keep University Mound open for at least another year, saying that if it closes, it will send the wrong message to the elderly. Campos said he was working to rescind the July 10 eviction deadline.

Reached for comment, Campos said just before the eviction deadline:

The squeeze is on, all over the City.

CPMC Suddenly Reconfigures St. Luke’s

After Mayor Lee proposed a really rotten deal in 2012 granting CPMC permission to build’s its “destination hospital” on Van Ness Avenue and build just an 80-bed hospital at St. Luke’s in the Mission District, the Board of Supervisors balked at the initial 80-bed agreement the Mayor had negotiated. They balked, in part, because although CPMC had pledged to keep St. Luke’s open for 20 years, the original agreement with the Mayor also contained a trigger that would allow CPMC to close St. Luke’s if CPMC’s systemwide operating margin fell below one percent for two years in a row.

Back in June 2012,

the San Francisco Bay Guardian reported that Supervisor Malia

Cohen had “criticized CPMC as an untrustworthy negotiating

partner. ’CPMC has an interesting corporate culture,’

she said, noting that the company has repeatedly misled supervisors

and community leaders, accusing it of being ’disingenuous

in its negotiations’.”

Back in June 2012,

the San Francisco Bay Guardian reported that Supervisor Malia

Cohen had “criticized CPMC as an untrustworthy negotiating

partner. ’CPMC has an interesting corporate culture,’

she said, noting that the company has repeatedly misled supervisors

and community leaders, accusing it of being ’disingenuous

in its negotiations’.”

The Bay Guardian reported that Campos had serious concerns of his own, reporting:

Lead by Supervisors David Campos and Mark Farrell, and assisted by Boudin Bakery co-owner and civic leader Lou Giraudo, who led mediations for the revised agreement, a compromise was announced on March 5, 2013, indicating that the Sutter Health affiliate will scale back the size of its planned Cathedral Hill Hospital from 555 beds to 274, and expand the capacity of a rebuilt St. Luke’s Hospital in the Mission District from 80 beds to 120.

Fast forward to 2014,

and suddenly CMPC resurfaced, apparently continuing to play its

games.

Fast forward to 2014,

and suddenly CMPC resurfaced, apparently continuing to play its

games.

On May 1, 2014 CPMC’s CEO, Warren Browner, MD, suddenly notified San Francisco’s Health Commission that CMPC intends to “realign our skilled nursing facility services.” Browner creatively claimed that the realignment did not “trigger” requirements under Proposition Q that the Health Commission would be required to hold a hearing to consider the potential detrimental impact on health care services to San Francisco, wrongly claiming that “skilled nursing facility services” are not covered by Proposition Q.

He’s wrong, because the November 1998 ballot measure passed by voters requires under Prop Q that private hospitals in San Francisco provide public notice prior to closing hospital inpatient or outpatient services, eliminating or reducing the level of services provided, or selling or transferring management of any hospital services.

Since CMPC’s SNF beds are tied to its hospital license, reducing those services automatically qualifies under Prop Q as a reduction in licensed services, no matter what Dr. Browner creatively claims.

As Chawla’s June 2014 memo to the Health Commission notes, CMPC proposed on May 1, 2014 to eliminate all 46 of its staffed SNF beds on its California campus by transferring 18 of the SNF beds to St. Luke’s and 4 to its Davies campus, eliminating the other 24 SNF beds altogether. CMPC admits that if the Health Commission approves CPMC’s newest proposal, its next step will be to petition the State to permanently reduce its total SNF bed license.

CPMC’s May 1 proposal will increase St. Luke’s SNF beds to a total of 77 SNF beds — 37 of which will be SNF beds, and 40 will be designated as “subacute care” beds. Subacute care is defined as skilled nursing beds for patients who don’t require care in an acute hospital, but require more intensive skilled nursing care than is typically provided to the majority of patients in a SNF. Subacute patients are typically medically fragile, and require specialized nursing services such as tracheotomy care, IV tube feeding, complex wound management, or inhalation therapy.

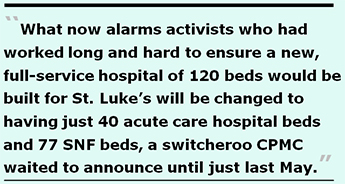

What now alarms activists

who had worked long and hard to ensure a new, full-service hospital

of 120 beds would be built for St. Luke’s will be changed

to having just 40 acute care hospital beds and 77 SNF beds, a

switcheroo CPMC waited to announce until just last May. Reasonable

people understand that you can’t run a full-service acute-care

hospital with just 40 acute-care beds.

What now alarms activists

who had worked long and hard to ensure a new, full-service hospital

of 120 beds would be built for St. Luke’s will be changed

to having just 40 acute care hospital beds and 77 SNF beds, a

switcheroo CPMC waited to announce until just last May. Reasonable

people understand that you can’t run a full-service acute-care

hospital with just 40 acute-care beds.

Activists remain concerned about what other unannounced plans CPMC may have to reconfigure St. Luke’s 120 beds after St. Luke’s and CMPC’s Cathedral Hill Hospital both open their new facilities, and whether this is just the beginning of converting the new St. Luke’s from a full-service hospital to other uses.

All of this flies in the face of the Health Care Service Master Plan (HCSMP) developed by the San Francisco Planning Department and the Department of Public Health that was adopted in October 2013. The HCSMP plan indicated a clear and increasing need for SNF beds in San Francisco.

CPMC’s sudden proposed “realignment” in use of St. Luke’s runs counter to the HCSMP, which warned that any reduction of SNF beds, regardless of type, will create an overall capacity risk for San Francisco and will likely have a detrimental impact on health care services in the community.

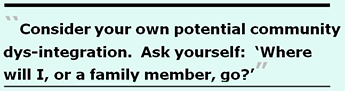

Consider your own potential community dys-integration. Don’t just ask “where will they go?”

Ask yourself: “Where

will I, or a family member, go?” Or ask, “What about

me?”

Ask yourself: “Where

will I, or a family member, go?” Or ask, “What about

me?”

Unless you have the resources to afford $10,000 monthly for long-term skilled nursing care at high-end private facilities such as the San Francisco Towers, The Sequoias in San Francisco, or The Heritage, you should probably plan to begin your search of where you will go, by looking first at out-of-county facilities.

Then start praying for the best.

Monette-Shaw is an open-government

accountability advocate, a patient advocate, and a member of California’s First Amendment Coalition.

He received the Society of Professional Journalists-Northern California

Chapter’s James Madison Freedom of Information Award

in the Advocacy category in March 2012. Feedback:

monette-shaw@westsideobserver.com.

Postscript

After submitting a condensed version of this article to the Westside Observer for its July issue, and while wrapping up this full version, new developments surfaced. Here’s a recap of the timeline of DPH’s nonsensical responses:

On April 29, Supervisor Campos’ aide, Carolyn Goossen had asked DAAS and DPH on behalf of Campos for relatively simple data between 2007 and 2014.

The Amended Data Response to Supervisor Campos Doesn't Make Sense

Supervisor Campos posed seven relevant follow-up questions to Hinton and Garcia, who have dodged providing straight answers for months. A comparison of Ms. Hiramoto’s initial and amended that responses the database didn’t work as designed are instructive. Data presented in red red were culled from hardcopy reports provided to Supervisor Campos.

|

Requested for FY 2007 — 2014 |

Response to Supervisor Campos |

Response to Supervisor Campos |

|

This is a follow up to your April 29, 2014 request. The RTZ software, did in fact, work as designed. We were able to run the report for the time period requested. The amended responses are as follows: |

||

| 1. The number of patients discharged from either LHH or SFGH to various “providers” (skilled nursing facilities, board and care homes, private homes, etc.), enumerating the number of aggregated patients discharged to each type of facility in-county. | We are sending the available TCM and Laguna Honda Hospital JCC Reports that cover the time period specified. We did not collect the data in a reportable manner for the years not included. |

According to data in the TCM hardcopy reports provided to Campos, there were:

|

| 2. The number of patients discharged from either LHH or SFGH to various “providers” (skilled nursing facilities, board and care homes, private homes, etc.), enumerating the number of aggregated patients discharged to each type of facility out-of-county. To be clear, we are requesting the LHH discharge data for discharges to facilities in San Francisco stratified separately from the data for out-of-county discharge facilities. | We are sending the available TCM and Laguna Honda Hospital JCC Reports that cover the time period specified. We did not collect the data in a reportable manner for the years not included. |

|

| 3. Aggregate data for each fiscal year listing the referral source (SFGH, each private hospital, board and care, direct-from-home, etc.) of patients who were referred for admission to LHH but were then diverted from admission to LHH, stratified by fiscal year and the aggregate number of patients for each referring source. | The data that was collected is incomplete. The software program designed to capture the data did not work as designed. |

The report does not provide data in aggregate; however, we ran the report for the time span requested and the outcome is as follows: 2011: 1. The request had sought a table stratifying

the number of diversions from each referring facility in each

of the 7 years of data requested. Hiramoto provided data

for only 2011, claiming a grand total of just two diversions

for the entire seven-year period.

3. For a high-end database such as SF GetCare, it seems implausible the system in incapable of providing aggregate data. |

| 4. Aggregate data for each fiscal year listing the types of facilities — board and care, SNF's, other facilities, etc. — that patients diverted from LHH admission were sent to, stratified by year and types of facilities and the aggregate number of patients involved. | The data that was collected is incomplete. The software program designed to capture the data did not work as designed. |

1 person went to hotel in San Francisco in 2011. 1 person went home with family in San

Francisco in 2011. 1. Because the TCM reports identified

at least 188 diversions from SFGH alone between 2007 and 2009

— without even adding in diversions from referring facilities

other than SFGH — the amended response is preposterous.

|

| 5. Separate aggregate data stratifying total discharges out-of-county, by age, gender, and ethnicity for all patients discharged from LHH, SFGH, or other DPH facilities, for each fiscal year. | The data collected is incomplete. Not all discharges include specific destinations and there is no data field within the LCRR to accurately pull discharge destination for every discharge during the specified time period. |

The data requested was to have been provided from module components of SF GetCare. The notorious “LCR” (Lifetime Clinical Record) system is an inappropriate source for data response. It appears Hiramoto did not run the report for the full time period — 2007 to 2014 — that Campos requested. |

| 6. Separate aggregate data stratifying total diversions out-of-county, by age, gender, and ethnicity for all patients who had applied for admission to LHH but were not admitted, for each fiscal year. | The data collected is incomplete. Not all discharges include specific destinations and there is no data field within the LCR to accurately pull discharge destination for every discharge during the specified time period. |

0 (zero) The data requested was to have been provided from module components of SF GetCare. The notorious “LCR” (Lifetime Clinical Record) system is an inappropriate source for data response. 1. The request was for the diversions

to have been stratified by age, gender, and ethnicity; for the

two diversions Hiramoto had claimed for 2011, she provided no

ages, genders, or ethnicities. |

| 7. Aggregate data on the number of requests for admission to LHH submitted to the DCIP screening committee stratified by year, indicating the total number of applicants actually admitted to LHH vs. the number of applicants diverted from admission. | The data that was collected is incomplete. The software program designed to capture the data did not work as designed. |

Total number of applicants diverted from Laguna Honda was 2 in 2011. 1. Because the TCM reports identified

at least 188 diversions from SFGH alone between 2007 and 2009

— without even adding in diversions from referring facilities

other than SFGH — the amended response of just two diversions

across a seven-year period ais preposterous. |

| Mivic [Hirose, LHH's CEO] will be sending you the JCC [hardcopy] Reports and any other available Reports that address the request under separate cover because the documents are many and it will be difficult to send as multiple attachments. Thank you for your patience |

It is not known why DPH and DAAS are struggling so mightily

to prevent release of this aggregate patient discharge data, but

it is suspected that the amount of out-of-county discharges and

diversions will reflect poorly on both departments and the City

of St. Francis. Surely, San Franciscans, and San Francisco legislators

charged with developing City policies, have a right to know just

how many discharges and diversions are occurring out-of-county.

Where are our “Old Friends” going?