Article Printer-friendly

PDF file

Westside Observer

June 2012 at www.WestsideObserver.com

Laguna Honda Hospital Book Review

Errors

Haunt “God’s Hotel”

by Patrick Monette-Shaw

One wonders whether God’s Hotel — just published

by former Laguna Honda Hospital physician Victoria Sweet, MD,

PhD — uses LHH as a backdrop to illustrate her career, or

to lament the loss of long-term care skilled nursing beds, a necessary

component of the “Slow Medicine” she advocates for.

While in many places

the book is insightful, to those who worked there and know the

hospital’s history intimately, the book’s omissions

and factual errors are disturbing.

While in many places

the book is insightful, to those who worked there and know the

hospital’s history intimately, the book’s omissions

and factual errors are disturbing.

Glowing reviews of God’s Hotel have appeared in

publications ranging from the Wall Street Journal, to the

Boston Globe, to the Huffington Post. But those

reviewers hadn’t witnessed events that transpired at Laguna

Honda as this reporter has for 13 years, and aren’t aware

of key errors in, and omissions from, God’s Hotel.

Aware since May 2010 Sweet’s book was in development,

during an invitation-only April 28, 2012 book launch party this

reporter was startled when Dr. Sweet indicated — literally

while passing — “Patrick, I hope you won’t be too

disappointed by what I left out,” (or words to that effect).

I wondered: Why had Sweet anticipated disappointment?

The book is an amalgam — part memoir, part a story involving

Sweet’s journey acquiring a PhD in the history of medicine,

and part an extended Op-Ed arguing for a return to “slow

medicine” — set against a backdrop of a very selective

history of nearly two decades of patients and staff at Laguna

Honda as it was transformed from a “medical model of care”

for poor, safety-net patients to a “social rehabilitation

model of care” for San Francisco’s homeless.

A central character in God’s Hotel — a title

taken from the French “Hôtel-Dieu,” a Middle Ages

“almshouse” taking care of the chronically disabled

— is twelfth-century mystic, nun, and medical practitioner

Hildegard von Bingen, whose idea was that human bodies are more

like a plant to be carefully gardened, rather than a machine of

broken parts. Sweet’s premise is that doctors should be more

like gardeners than mechanics, and that many non-desperate illnesses

might be better treated by Slow Medicine, by nurturing viriditas,

the natural greening power of healing.

Throughout the book, Sweet offers many insights that take your

breath away. In one patient vignette about having an accurate

diagnosis, Sweet notes she saved the healthcare system approximately

$400,000 by making the correct diagnosis that an artificial hip

had been dislocated from its socket, detected by a relatively

inexpensive X-ray. “If doctors were going to held accountable

for [healthcare] costs,” Sweet writes, “why shouldn’t

we get some kind of credit for savings?”

In another vignette, Sweet acknowledges that “almost every

patient I admitted had incorrect or outmoded diagnoses,”

often taking medications for diagnoses they didn’t have and

placing patients at risk for adverse outcomes. Many of the misdiagnoses

Sweet attributes to over-zealous medical student interns at San

Francisco General Hospital, who are apparently never held accountable

for misdiagnoses that drive up healthcare costs and endanger patient

outcomes.

She wonders how outcomes might be improved with correct diagnoses,

instead of incorrect ones, and visits to emergency rooms avoided

if doctors are provided sufficient time to spend with patients.

These insights — and others — make God’s Hotel

an important read.

But maddeningly, although Sweet acknowledges Hildegard “took

care to mention dates in her writing … to preserve her work

for the future,” Sweet avoided including any dates throughout

God’s Hotel’s 348 pages (although a few dates do appear

in the end notes at the end of the book), making it all but impossible

for readers to place events at LHH and during her PhD studies

into perspective. How could any historian with a doctorate in

medical history write a book with no dates documenting a hospital’s

history?

From the vignettes, Sweet concludes LHH’s three principles

are “hospitality,” “community,” and “charity.”

She relates these principles by examining the etymology of many

Latin words, including curare, splitting cure (doctors)

and care (nurses), that has long fueled a battle for command and

control of hospitals. Which model — care (nurses) or cure

(doctors) — would triumph at Laguna Honda?

Sweet notes that during the French Revolution, medicine began

to change; doctors wanted control of the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris

to correlate medical treatments with patient outcomes. The nuns,

of course, objected on moral grounds that using patients as experimental

things was a bad idea; they protested, refusing to serve under

the doctors and refusing to leave. Eventually, administration

rescinded its order giving doctors control, returning control

of the Hôtel-Dieu to the nuns providing nursing, until they

left after it was secularized in the 1900’s.

Much of Laguna Honda’s history during the past 20 years

parallels the same battle for control, a feud between doctors,

nurses, and administration played out in most hospitals to this

day. For her part, Sweet acknowledges the dynamic between the

Nursing, Hospital Administration, and Medicine departments needs

to be kept in close check to advance optimal patient outcomes.

In a long vignette about a patient with transverse myelitis,

an inflammation of the spinal cord, Sweet’s point of view

changed from focusing on her patients “vaguely surrounded

by his environment.” Instead, she stepped back and learned

to focus on the environment surrounding her patients, asking herself

when anything interfered with her patient’s natural healing

powers and their environments, what she could do to remove it.

Throughout the book, it becomes clear that Sweet didn’t

venture into the political environment at Laguna Honda, and didn’t

become involved in efforts to stop the transformation of its medical

model of care, or efforts to permanently alter LHH’s environment.

Sweet acknowledges that the same disability rights activist

lawyers who disastrously shut down state mental hospitals around

the country are now the same people hell bent on shutting down

skilled nursing facilities caring for the frail elderly. Their

test case was shutting down Laguna Honda Hospital.

Sweet erroneously reports that just after John Kanaley was

appointed as Laguna Honda’s Executive Administrator in 2004,

Sister Miriam Walsh requested a meeting with him. In fact, within

the first month of his tenure, Kanaley summoned three vocal LHH

staff members to his office in a bald attempt to exert his authority.

None of the three had requested meeting with him.

First, he summoned Sister Miriam Walsh to his office for a

discussion about her advocacy against the “flow project”

involving the transfer of psycho-social patients from San Francisco

General Hospital to LHH. When asked what Kanaley wanted, Sister

Miriam reported “He wanted me to agree to a deal to keep

Laguna Honda’s name out of the media and asked me to pipe

down. I told him, ’No deal,’ and that was the end of

the meeting.“

In short order, Kanaley summoned Dr. Maria Rivero and this

reporter, separately, to his office for the same talk, and we

both essentially told him the same thing: “No deal.”

Kanaley’s attempt to bully vocal staffers by intimidation

set the tone for the duration of his bull-in-a-China-shop administration.

In another act of bullying, in June 2008 — following Sister

Miriam’s May 2008 Westside Observer article “Farewell

to Laguna Honda’s Clarendon Hall” — Kanaley wrongly

accused this author of abusing Sister Miriam as a frail, elderly

woman to advance my political and personal “gain,” because

he falsely assumed I had written her article, which was a complete

lie.

Many Minor Errors …

In the chapter “Wedding

at Cana,” Sweet describes the wedding of two patients —

the “Teal’s” — in LHH’s chapel, comparing

it to Jesus’ first miracle, the transformation of water

into wine at a wedding in Cana. From this, Sweet concludes —

quite ironically — that Laguna Honda’s second principle

is “community.”

In the chapter “Wedding

at Cana,” Sweet describes the wedding of two patients —

the “Teal’s” — in LHH’s chapel, comparing

it to Jesus’ first miracle, the transformation of water

into wine at a wedding in Cana. From this, Sweet concludes —

quite ironically — that Laguna Honda’s second principle

is “community.”

Sweet asserts “almost all of Laguna Honda” poured into

LHH’s Chapel for the Teal’s wedding, but observers

report that attendance was actually quite low. Some observers

wonder whether the stretched attendance was carried over into

other areas of God’s Hotel for literary effect. The

exaggeration, in itself, wasn’t terrible, but why do it,

they wonder?

But the irony is that the low turnout may have been because most

staff at LHH were painfully aware that Bride Teal was, in fact,

already married to another man; many staff may have stayed away

from the wedding, not wanting to witness polygamy being blessed.

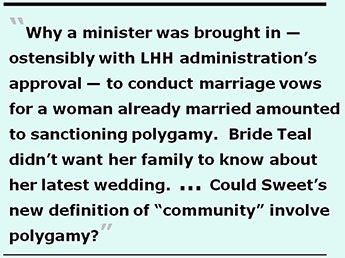

Why a minister was brought in — ostensibly with LHH administration’s

approval — to conduct marriage vows for a woman already

married amounted to sanctioning polygamy. Bride Teal didn’t

want her family to know about her latest wedding. Rather than

providing her with a reality check that she could have a party

with her new love, but couldn’t throw a full-fledged wedding

because she was already married to someone else, a handful of

staff chose to “enable” Bride Teal, fueling her fantasies.

Could Sweet’s new definition of “community” involve

polygamy? Why did Sweet choose this story to illustrate “community,”

when there were so many other examples of real community at LHH

that she could have drawn from?

- Sweet reports that voters passed Prop. “A” in 1999

to rebuild LHH for $500 million, and that half would come from

a general obligation bond and half from the tobacco settlement

revenue account. This is untrue: First, voters were told the

hospital’s replacement budget was $401 million, not $500

million (although the cost overruns 12 years later pushed the

cost to well over $593 million). Second, the bond was for $299

million, and just $100 million was to come from the TSR account,

not half and half.

- Sweet accurately reports there were two committees involved

in the 2006 Prop. “D” ballot measure: “San Franciscans

for Laguna Honda,” and the “Committee to Save Laguna

Honda.” But she misreports that doctors Kerr and Rivero

were members of both committees. This is patently untrue. The

latter committee was formed by this author, Sister Miriam, Virginia

Leishman, LHH resident Robert Neil who was then president of

the Resident’s Council, and family members of the Traumatic

Brain Injury Support Group. At the time, Kerr and Rivero made

the correct ethical decision that they could not violate their

doctor-patient relationships by joining an advocacy group that

included patients of the facility.

- Sweet asserts the hospital’s 1,200-bed replacement plans

had included three identical six-story buildings. In fact, the

third residential tower eventually eliminated was a 420-bed,

seven-story building containing crucial infrastructure elements

like the data center that then had to be shoehorned into one

of the two remaining 320-bed six-story buildings.

- Sweet reports that following a meeting between Sister Miriam

and Mayor Gavin Newsom, Newsom ordered then Director of Public

Health Mitch Katz to halt the many incarnations of the so-called

“Flow Project” shuttling SFGH patients to LHH. Since

this reporter attended that meeting, I can vouch that meeting

wasn’t with the Mayor, it was with his Chief of Staff Steve

Kawa, who has long been considered San Francisco’s real

mayor ever since Willie Brown’s tenure. Earlier, this reporter

had also attended a meeting between Sister Miriam and Mayor Newsom,

which also included former City Attorney Louise Renne —

the chairperson of the Laguna Honda Foundation — but Sweet

makes no mention anywhere in God’s Hotel about Renne’s

meddling in Laguna Honda’s affairs.

There are a host of other minor errors.

… Along With Many

Major Errors

- When Sweet turned her attention to the U.S. Department of

Justice’s first letter to then mayor Willie Brown in May

1998, she speculates the DOJ had been “tipped off”

to investigate LHH. Sweet dissembles, first speculating it may

have been doctors Kerr or Rivero who contacted the DOJ, before

Sweet then speculates it may have been LHH’s forty-four-year

Director of Nursing Virginia Leishman who provided the DOJ a

tip, an allegation Leishman adamantly denies. (Leishman has,

reportedly, received numerous calls since God’s Hotel

was published, some encouraging her to consider slander.)

Observers at the time note that it may have been a former LHH

Executive Administrator who may have “tipped off” the

DOJ if anyone had, since he may have been miffed when plans to

hand him a job converting the Department of Public Health into

an “enterprise” department that would receive no City

General Fund support fizzled, along with his promised job. Regardless,

there is no proof that the DOJ had received any

tips, and may have launched its investigation simply by reviewing

sentinel event, or annual inspection, reports.

- Referring to the same first letter from the DOJ, Sweet asserts

the DOJ was initially concerned only about LHH’s Nursing

department, saying the DOJ blamed Nursing for almost everything,

except LHH’s old-fashioned wards and aging infrastructure.

This is also patently untrue. The DOJ, in effect, also blamed

the Department of Medicine — which had then rightfully contained

the sub-specialty of physical medical rehabilitation, including

speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physical therapy, all

components of physical medicine — for failing to provide

specialized rehabilitation therapy. The DOJ asserted in 1998

that only 50 residents were receiving physical, occupational,

or speech therapy — which services require referrals from

physicians — to prevent functional decline, failing health,

and premature death.

Speech Therapy, the DOJ claimed, had only assessed one-third

of residents at LHH who were at risk for aspiration, and had

assessed only 70 of 700 residents requiring eating assistance.

As a result of the DOJ’s claim in 1998, Laguna Honda hired

within a year a new senior physical therapist, an occupational

therapist, and a speech pathologist charged with developing a

functional maintenance and restorative care program that subsequently

hired four therapy aides to implement the program, which initially

proved to be a success. (Unfortunately, that program has fallen

into disrepair, given intermittent curtailment of restorative

care services on long-term care units.) Before each return DOJ

visit across the next decade, LHH physicians increased their

rehabilitation physician orders to avoid further DOJ wrath. That

meant doctors were finally paying attention to writing rehab

referrals.

The DOJ was also critical in 1998 of LHH’s Activity Therapy

Department for not providing meaningful activity needs of LHH

residents. The DOJ’s concerns weren’t attributable

solely to Nursing.

- Sweet reduces to a single page the 2006 Proposition “D”

ballot measure to protect Laguna Honda for the frail elderly

with skilled nursing needs, as voters were promised by Prop.

“A” in 1999. Sweet wrongly regurgitates — with

no critical analysis — the lies Prop. “D” opponents

used to defeat the measure: That the proposition would permit

the Residential Builders Association to build for-profit residential

care facilities on city land, would put a zoning administrator

in charge of making hospital admission decisions, and would require

LHH to discharge 300 Alzheimer’s and AIDS patients, all

of which were lies.

The RBA had no interest in building residential care facilities.

The land use attorney who crafted the language for Prop. “D”

— being an associate of former City Attorney Louise Renne

who now operates the Laguna Honda Foundation — slipped in

arcane language thought required for Planning laws, but was actually

twisted into possibly allowing for for-profit private development.

Nothing in Prop. “D” allowed for-private development,

but once City Attorney Dennis Herrera wrote that Prop. “D”

would provide a “land grab” by private interests, the

lie stuck, despite being a canard uncovered by a respected journalist

who looked into the issue and exposed it to be false.

Worse, lacking further critical analysis, Sweet omitted that

LHH’s then Rehabilitation Coordinator was the only LHH staff

member not affiliated with Prop. “D” who had correctly

noted in 2006 that Prop. “D” used the exact

same language that was contained in Title 22 and LHH’s own

admission policies; he had read Title 22. The dullards running

the anti-Prop. “D” campaign — including the Director

of Public Health Mitch Katz, Mr. Kanaley, Mivic Hirose, and many

MD’s on LHH’s staff — all appeared to have turned

a blind eye to Title 22, as if they’d never read it.

- Sweet doesn’t report that in March 2006 — despite

a prohibition in San Francisco’s Administrative Code Section

12G against using city funds to attempt influencing political

activity, including ballot measures — then City Controller

Ed Harrington, City Services Auditor Leticia Miranda in the Controller’s

Office, and Health Management Associates employee Nicola Moulton

exchanged a series of e-mails outlining the Prop. “D”

ballot initiative and “themes” that might be used to

defeat the measure, including whether 300 Alzheimer’s and

Parkinson’s patients were part of those who would face discharge

if Prop. “D” passed. Harrington and Miranda had to

have known — if Sweet didn’t — that Health Management

Associates was a contractor receiving city funds who had made

recommendations in 2005 to alter Laguna Honda’s service

mix. They also had to have known that using a city contractor

to help develop arguments to defeat a ballot measure clearly

violated Section 12G. Sweet mentions nothing of this.

Nor does Sweet mention that prior to publication of God’s

Hotel, she had to have heard news that San Francisco’s Director

of Public Health Mitch Katz had been paid $30,000 over a three-year

period by Health Management Associates, the same firm he had

steered a contract to.

- Sweet reports that Dr. Katz had given Mr. Kanaley an additional

$10 million for more “administrative staff,” but she

neglected to mention the $10 million was for transition planning

to the new facility, including a host of duplicative doctors

and nurses — not administrators — to ensure regulatory

compliance. And Sweet omits that much of the $10 million wasn’t

encumbered until after the move into the new facility

had been completed; was possibly not used as intended by the

initial earmark; that as of May 2012, only 74% of the $10 million

had been spent; and that the remaining 26% ($2.6 million), had

been cost-shifted to funding “facility maintenance contracts,”

instead.

There are other major errors too long for this review.

Glaring Omissions

- Sweet mentions nothing about the closure of LHH’s adult

day health care program, nor does she discuss the loss of 200

to 300 assisted living facility beds planned for the facility.

Nor does she discuss the impact of the loss of LHH’s 420

skilled nursing beds on the rest of the city, and its effect

on discharge locations, either. None of this is discussed in

relation to “slow medicine.”

- There is no mention of the $190 million in cost overruns

of the replacement facility, nor the shoddy workmanship in the

new buildings (mold in the new kitchen is but just one problem)

that will cost additional millions to repair.

- While Sweet acknowledges LHH’s current medical director

relocated her offices to the front of the building to signal

that the Medical Staff was falling into alignment with the Hospital’s

Administration to transform LHH, Sweet fails to note that this

medical director also jettisoned the medical staff’s autonomy

when she permitted Rehabilitation Services — whether or

not with concurrence by LHH’s Chief of Rehabilitation Services

Lisa Pascual, MD, and LHH’s then Rehabilitation Coordinator,

Paul Carlisle — to be placed under the auspices of the hospital’s

Facility Operations Department. As far as is known, no other

physical medicine rehabilitation department or their parent medical

services department in Bay Area hospitals have permitted being

placed under the control of facilities operations staff.

- While Sweet reports doctors Rivero and Kerr had filed a whistleblower

complaint about abuse of LHH’s patient gift fund, Sweet

never mentions that following a long-delayed City Controller’s

audit of the gift fund the hospital was eventually ordered to

restore over $350,000 misappropriated from patient benefit.

- Similarly, while Sweet notes that doctors Kerr and Rivero

had authored a “brilliant” rebuttal to the Davis Ja

report that recommended “higher-salaried physicians be replaced

by registered nursing staff, social workers, and psychologists,”

Sweet excluded reporting that over 20 physicians at LHH had signed

a letter of support, finding that the Ja report had been illegal,

unethical, and harmful to patients, since Ja lacked professional

qualifications to assess physician services.

- Although Sweet rightfully lambasts in God’s Hotel

the “social rehabilitation” grant LHH’s Executive

Administrator Mivic Hirose secured that became the focus of a

heated, politically charged Board of Supervisors hearing in 2005,

Sweet failed to note that during the final PowerPoint presentation

at the end of the grant, the Nursing Team involved admitted it

had not actually implemented any Nursing “intervention”

portion of the grant designed to prove to the funding source

the efficacy of social rehab interventions, a glaring admission

of failure.

Nowhere does Sweet delve into the LHH public relations director’s

spin control “deconstruction”; he’s the guy who

claimed “LHH’s patient gift fund isn’t for patients.”

Marc Slavin was hired in 2007 to squelch “negative publicity

about LHH” to help out his benefactress, former City Attorney

Louise Renee, now head of the Laguna Honda Foundation non-profit

that refuses to release any details of its income and expenses,

a fact Sweet must have know about for years, but doesn’t

address.

To her credit, Sweet does acknowledge that San Francisco mounted

no legal defense against either the Davis lawsuit or the

Chambers settlement agreement; the City, with Slavin’s

help, simply capitulated to the disability rights activists intent

on shutting down Laguna Honda Hospital, contributing to the abuse

of this civic institution.

Slavin is reportedly pursuing a PhD degree. While Sweet rightfully

wonders about efforts to re-brand a public hospital with a new

name that Slavin had proposed eliminating “hospital”

from, she doesn’t wade in to whether Slavin’s marketing

efforts over the years are designed to re-frame, for advertising

purposes, that LHH can be used for just about anything, perhaps

part of his pursuit of a PhD. He and Renne are at it again, now

trying to “re-brand” LHH’s patient auditorium into

a revenue-generating community theater to support Renne’s

non-profit Laguna Honda Foundation.

Sweet never addresses LHH Administration’s ascendancy

under Slavin, and the negative impact Administration has had on

patient outcomes, while casting Nursing and Medicine asunder.

God’s Hotel is certainly no match against Slavin’s

considerable skills in on-going deconstruction, and may be too

little, too late to stop the transformation in how we provide

“slow medicine” to care for the sick poor.

Despite errors haunting God’s Hotel, it may still

be worth a read.

Monette-Shaw is an open-government accountability advocate,

a patient advocate, and a member of California’s First Amendment

Coalition. He received the Society of Professional Journalists–Northern

California Chapter’s James Madison Freedom of Information

Award in the Advocacy category in March 2012.

Feedback: monette-shaw@westsideobserver.com.

Top

_______

Copyright (c) 2011 by Committee to Save LHH. All rights

reserved. This work may not be reposted anywhere on the

Web, or reprinted in any print media, without express written

permission. E-mail the Committee

to Save LHH.

While in many places

the book is insightful, to those who worked there and know the

hospital’s history intimately, the book’s omissions

and factual errors are disturbing.